Blackface minstrelsy is a 19th-century, American theatrical form of entertainment. It has been in Canada since the 19th century. Originated by white men in the Northern United States, it depicted parodies of enslaved Black people on southern plantations and free Black people in the North. (See Black Canadians.) By the 1860s, there were homegrown, Canadian blackface stars of the stage who toured Canada, the United States and Britain. Blackface was a widespread form of mass entertainment into the 20th century. Today, blackface is considered racist but remains widely discussed and debated. (See Anti-Black Racism in Canada.)

Origins of American Blackface

Blackface minstrelsy originated in the United States. It was a theatrical form where white actors put on burnt cork makeup to offer supposed aspects of African American culture. The makeup was usually a combination of burned and pulverized champagne corks with water. Beginning in the 1830s and 1840s, early minstrelsy was shaped in part by three Northern white men ― Thomas “Daddy” Rice, Dan Emmett and Edwin Pearce Christy ― and Stephen Foster, the major innovator of minstrel music.

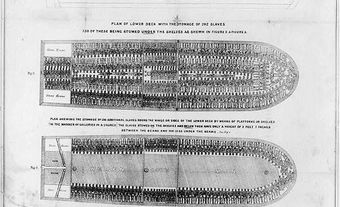

American blackface explicitly borrowed African American cultural expressions such as dance and song. This borrowing also touched on the themes of slavery. White artists used the stage to obscure the realities of enslavement. (See also Black Enslavement in Canada.) They depicted “happy slaves” dancing and singing on plantations. Audiences were led to believe that slavery was just and right. Blackface minstrelsy was ultimately very powerful because it distorted the reality of American slavery. As African Americans were challenging slavery laws in the decades leading up to the American Civil War, on the minstrel stage, they were depicted as a people content with being enslaved.

In 1829, George Washington Dixon released “Coal Black Rose” ― a derogatory song about Black courtship. It perhaps became the first blackface minstrel song to enter the Great American Songbook. Around 1830, “Daddy” Rice became an international sensation when he began imitating a shuffle he had seen performed by a Black man in Louisville, Kentucky. His “Jim Crow” tour visited Canada and Britain. The performance popularized blackface as a form of large-scale theatrical entertainment.

In 1843, a quartet, calling themselves the Virginia Minstrels, took the stage at New York’s Chatham Theatre. The four Northern white men ― Dan Emmett, Billy Whitlock, Frank Brower and Dick Pelham ― called themselves “minstrels”' because of the great success of the Tyrolese Minstrels, a Swiss singing family that had toured America in the early 1840s. The name also enhanced claims of Southern authenticity. After 1843, the term “minstrelsy” was added to blackface to stand for theatrical performances with white men wearing burnt cork.

Early minstrelsy was rather unstructured. In the 1840s, a set three-part structure evolved. The first part consisted of jokes and songs. The second part was a mix of “stump speeches” and other variety acts in the middle. Finally, a plantation skit (later replaced by a burlesque skit) was performed last.

Tom Shows in Canada

American minstrel clowns first began touring Canada in the 1790s. By the 1820s, theatres and music halls opened to support concerts and circuses.

In the mid-19th century, many African American freedom seekers came to Canada via the Underground Railroad. Blackface productions of Harriet Beecher Stowe’s 1852 novel, Uncle Tom’s Cabin, called “Tom Shows” also appeared. (See also Josiah Henson.) These shows attracted a large segment of the population that would otherwise never expose themselves to the theatre.

Uncle Tom’s Cabin was one of the first American novels with a Black main character. It not only galvanized support for the abolitionist movement to end slavery (see also Anti-Slavery Society of Canada) but it also likely popularized the stereotype of free Northern Black people versus enslaved Southern Black individuals. Unlike the novel, the blackface show had song and dance numbers. The shows also pitted these duelling characters against each other (one free, one enslaved) to amuse white audiences.

By the 1850s, the anti-slavery movement was expanding in Canada. Canadians might not have supported the enslavement of Black people but many enjoyed watching and listening to blackface minstrel songs. These were often rooted in a false narrative of “happy” Black slaves in the South, and out-of-place and ill-dressed free Blacks in the North. Blackface obscured the realities of slavery.

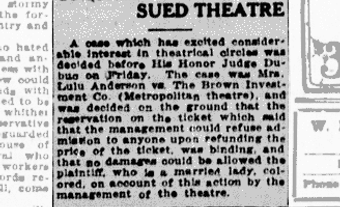

From 1840 to 1843, Toronto’s Black community petitioned city council to prohibit touring blackface minstrel clowns. Many community members feared that such protests would incite racist repercussions. (See Anti-Black Racism in Canada; Racial Segregation of Black People in Canada.) However, the pervasiveness of newspaper advertisements for minstrel shows from the 1850s through the 1920s, shows that the Black community’s protest did little to diminish white Canadians’ appetite for blackface theatre.

Canadian Blackface Performers

Colin “Cool” Burgess was one of the most successful Canadian-born minstrel performers of the 19th century. Born in Toronto, Burgess toured with a succession of American companies in the 1860s.

Born in Quebec, Calixa Lavallée achieved success in American minstrelsy in the 1850s and 1860s. Most remembered as the composer of “O Canada”, Lavallée toured many cities and towns as a musician. He did so in blackface while leading a band each night.

Contemporary Use of Blackface

In the 20th century and beyond, blackface became a central part of the film industry, such as The Birth of a Nation (1915), The Jazz Singer (1927) and Holiday Inn (1942). Many actors used makeup to play racialized characters. By the 1960s, however, in response to ongoing civil rights protests and shifting cultural norms, blackface fell out of popularity in entertainment.

Blackface may have left the big screen, but it still exists. In 2015, Joni Mitchell revealed that she posed in blackface for the 1977 album Don Juan’s Reckless Daughter. In 2019, pictures of Prime Minister Justin Trudeau wearing blackface in the early 2000s were published. Trudeau apologized and recognized that his actions were racist.

Today, blackface is considered racist. For advocates, its origins in the theatre ask that we think about Black representation in the entertainment industry and race relations in the contemporary. (See also Anti-Racism Education in Canada.)

Share on Facebook

Share on Facebook Share on X

Share on X Share by Email

Share by Email Share on Google Classroom

Share on Google Classroom