Frederick Ogilvie Loft (commonly known as Fred or F.O. Loft), Mohawk chief, activist, war veteran, reporter, author and lumberman (born 3 February 1861 on the Six Nations reserve, Grand River, Canada West [ON]; died 5 July 1934 in Toronto, ON). Loft founded the League of Indians of Canada, the first national Indigenous organization in Canada, in December 1918 (see Indigenous Political Organization and Activism in Canada). He fought in the First World War and is recognized as one of the most important Indigenous activists of the early 20th century. His Mohawk name was Onondeyoh, which translates as “Beautiful Mountain.”

Frederick Ogilvie Loft (also known by his Mohawk name Onondeyoh) was a well-known Mohawk activist who founded the League of Indians of Canada.

Early Life

Fred Loft was born to George Rokwaho Loft and Ellen Smith (also known as Konwajonhondyon, which translates as “left alone by the fire”). They were Mohawk Christians from the Six Nations ( Haudenosaunee) of the Grand River in Ontario. Loft’s mother gave her children both English and Mohawk names. Ellen Smith was the granddaughter of Oneida Joseph, who fought on the British side with the great Mohawk warrior Joseph Brant (Thayendanegea) in the American Revolutionary War (1775-83, see American Revolution - Invasion of Canada).

Loft’s parents spoke English and Mohawk fluently, and they encouraged him to focus on education from an early age. Loft attended a First Nation elementary school near Forest Home until he was 12 years old. He was then sent to a boarding school called the Mohawk Institute, a residential school in Brantford, Ontario. Loft hated this school, saying later that he was hungry and cold all the time: “In winter, the rooms and beds were so cold that it took half the night before I got warm enough to fall asleep.” With the support of his parents, Loft left the residential school after one year.

When he was 13, Loft attended a public school in Caledonia, a non-Indigenous town. However, he had to walk nearly eight miles a day (nearly 13 km) to school. Because of this, he moved to Caledonia the next year, working for his room and board. After graduating from elementary school, Loft attended high school in Caledonia from 1878 until 1881.

Early Career

After Fred Loft completed high school, he worked various jobs. This included several years in the forests of northern Michigan, where he began as a lumberjack and rose to the rank of timber inspector. He returned to the Grand River in 1884 or 1885, receiving a scholarship to study bookkeeping at the Ontario Business College in Belleville, Ontario.

Finding no work as a bookkeeper, he took a job for six months as a reporter for the Brantford Expositor. During his time as a reporter, Loft covered the general (federal) election of February 1887 (see Canadian Elections). This election was significant for Indigenous peoples because all Indigenous men in Eastern Canada who met the property qualification had recently become eligible to vote (see Indigenous Suffrage). However, Indigenous men would lose the federal franchise again in 1898. The struggle for the franchise increased Loft’s interest in First Nations rights.

After leaving the Brantford Expositor, Loft worked for two years as a lumber inspector in Buffalo, New York. He moved to Toronto around 1890, accepting the position of accountant in the bursar’s office of the Asylum for the Insane in the provincial Liberal government of Oliver Mowat. Loft, a staunch Liberal himself, remained in the civil service position for 36 years.

Pre-war Activism

During his time in Toronto, Loft began to work as an Indigenous activist. Among other proposals, he sought to organize a new political organization of the First Nations of Ontario. He suggested that the Ojibwe and Haudenosaunee (Iroquois) come together to join a new pan-Indigenous organization (an organization devoted to bringing together Indigenous nations for a common cause). Loft outlined this proposal in a letter to the Toronto Globe on 7 November 1896. His primary concern was increased autonomy for Indigenous peoples in Canada. Despite continuing to advocate for Indigenous concerns in the 1890s, Loft was unsuccessful in his goal of creating a new organization for the First Nations of Ontario.

In the early 20th century, Loft continued to promote Indigenous rights, using his experience as a journalist. In 1908, for example, he wrote about Indigenous issues for the Toronto Globe. In 1909, he wrote a series of articles on Indigenous education for the popular Toronto magazine Saturday Night. In the first article, Loft called for the closing of residential schools, which he described as “veritable death-traps.” Instead, Loft promoted the creation of day schools for Indigenous children on reserves. Loft also wrote articles praising “Iroquoian loyalists” like Joseph Brant (Thayendanegea). As a devoted loyalist, Loft admired Mohawk warriors who fought heroically for their own people and the British Crown.

Marriage and Family Life

After moving to Toronto around 1890, Fred Loft met Affa Northcote Geare. They were married in June 1898. Geare was from Chicago, a former Torontonian of British ancestry who was active in the American Women’s Club of Toronto, the United Empire Loyalists’ Association of Canada and the Women’s Art Association of Canada. They had three daughters, one of whom died at a young age.

Military Career

When the First World War began in August 1914, Fred Loft strongly encouraged other Indigenous men to enlist. Given his own family’s history of supporting Great Britain in times of war and his own loyalist beliefs, Loft believed it was their responsibility to support Canada and the British Empire in its time of need. Loft’s ancestors, the Six Nations (Haudenosaunee), had sent warriors to fight alongside British troops in previous wars, such as the War of 1812.

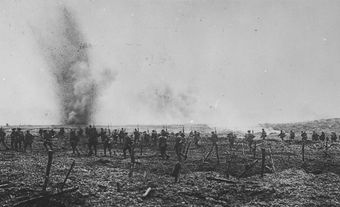

In 1917, after three years of active militia service in Toronto, Loft was commissioned into a forestry company as a lieutenant. He was sent to a forestry unit because of his extensive experience in the lumber industry. He was 56 years old at the time, but he lied to recruiters and told them he was only 45 so he would not be turned away. Loft sailed to Britain with the 256th Infantry Battalion (Canadian Expeditionary Force) but was transferred to the Canadian Forestry Corps. He also spent some time in France.

On 7 August 1917, during his time overseas, the Six Nations Council awarded Loft a pine tree chieftainship. This was a great honour, given only to the most respected members of the Grand River Iroquois (Haudenosaunee) Confederacy. On 21 February 1918, before leaving for Canada, he met King George V at Buckingham Palace on behalf of the Six Nations Council.

Did You Know?

In 2020, Fred Loft made the Bank of Canada’s short list of people under consideration to appear on a newly designed five-dollar bill.

Founding the League of Indians

Before the end of the First World War, Loft made plans for what he eventually called the League of Indians — an organization he envisioned as advocating for Indigenous rights in Canada. As he had done before the war, he pushed for the improvement of education for Indigenous peoples, especially more day schools and high schools on First Nations reserves.

After the war ended in 1918, Loft realized another reason to create a pan-Indigenous organization — poor and unequal treatment of Indigenous veterans. Former Indigenous soldiers were treated unfairly by Indian Affairs; for example, they received fewer benefits or smaller pensions (or were denied pensions) for their military service upon return to Canada. Loft hoped that if Indigenous individuals and groups banded together, they could protect their rights from the Canadian government.

In December 1918, Loft founded the League of Indians of Canada at the Six Nations Reserve's Council House in Ohsweken. Loft was inspired by the ancient Iroquois League (Haudenosaunee Confederacy), which may have been founded as early as 1142 CE. The new organization became the first pan-Indigenous political organization in Canada, holding annual meetings in various parts of the country from 1919 to 1922.

Although he received some support from Indigenous leaders and other activists, Loft found that he was largely alone in maintaining the League of Indians. Loft used his own resources and money from his civil service job to help run the organization, acting as president and secretary-treasurer.

Indian Affairs (see Federal Departments of Indigenous and Northern Affairs) consistently refused his requests to speak directly to the Canadian Parliament. Loft was seen as a subversive (dangerous radical) by Duncan Campbell Scott, the deputy superintendent of the Department of Indian Affairs from 1913 to 1932. Scott, the highest-ranking cabinet member on matters concerning Indigenous affairs, consistently undermined both Loft’s leadership and the League of Indians organization. As a result, the League of Indians became defunct by the early 1930s, largely the result of a lack of resources and the deliberate opposition from Indian Affairs.

Death and Legacy

Fred Loft died in Toronto in 1934 following a period of declining health. His advocacy work before and after the First World War make him one of the most important Indigenous activists of the early 20th century. Though the League of Indians was short-lived, it is now regarded as a precedent for other nationwide Indigenous political organizations, such as the National Indian Brotherhood, formed in 1968, and its successor, the Assembly of First Nations, created in 1982.

Share on Facebook

Share on Facebook Share on X

Share on X Share by Email

Share by Email Share on Google Classroom

Share on Google Classroom