Pat Adachi was born and raised in Vancouver, the daughter of Japanese immigrants. She grew up in the heart of the city’s Little Tokyo neighbourhood, within walking distance of the local grounds where her father would take her on Sundays to watch her favourite baseball team, the Vancouver Asahi. Adachi and her family lived normal lives, until she and her community were uprooted in 1942, when the federal government ordered Japanese Canadians to internment camps in rural British Columbia (see Internment of Japanese Canadians).

In this interview, Adachi shares her story and relates the experiences of the 22,000 Japanese Canadians who were interned in Canada during the Second World War.

This interview has been edited for length and clarity.

Having been born in Canada, can you explain the feeling of suddenly being considered the ‘enemy’ despite your Canadian roots?

I was 21 years old when Japan bombed Pearl Harbour and war was declared.

All the Japanese were considered enemy aliens. Most of us in the second generation were born in Canada. That didn’t matter. We had veterans from the First World War that fought for Britain and Canada. They had been at Vimy Ridge…. Didn’t matter. We were all enemy aliens.

Now, there was never any doubt with the RCMP — they said the Japanese never created any problems. The police said you couldn’t find a Japanese that committed any crime. That didn’t matter.

Eventually, Mackenzie King declared that all Japanese had to be removed from the coast line.

Was there a feeling that the decision would be permanent?

At first, we thought [internment] wouldn’t last very long. My father came from Japan so he said that, being a national, he would be moved some place. He wanted me to get married. My future husband Harry and I had been going around, and my father wanted someone to look after the family. We got engaged that Christmas and got married in January of 1942. My father was sent to a road camp in March of that year. That’s what happened to most nationals.

We thought that would be the end of it. But, then, the people of the coast line and Vancouver Island were given less than 24 hours’ notice and then removed from their homes and brought to Vancouver and put in the exhibition grounds — some even in the animal stalls.

It didn’t end there. Eventually, they had to do something with all the Japanese, and they confiscated our properties. Every last thing. Homes, our farms, all of our vehicles, even radios and cameras.

My husband was sent to work as a foreman on the exhibition grounds helping to maintain the grounds, along with a few of his friends. But in June 1942, they too were moved out and sent to different ghost towns, abandoned mining hubs.

I was with my mother and my sister; my father had owned a rooming house, and we were still able to live there. But we were called in, I guess it was about August. We were put on these dusty trains and moved out. We didn’t know where we were going.

We ended up in a place called Slocan [Valley]. Slocan was divided into four areas: Slocan City, Bay Farm, Popoff, and Lemon Creek. [Pat and her family lived in Popoff.]

What was it like when you first arrived?

At first the homes were not ready, so we lived in tents and ate in mess houses.

It was a very cold winter. We had no running water. I lost my first baby. There were just no facilities.

I’m so sorry to hear that, Pat. How did you manage to get through something like that?

We were all in the same boat. Nobody had anything, so we shared. Our first generation — our parents — were very resilient. They didn’t sit around complaining about what the government had done. They got busy and made gardens — somebody had the foresight to bring seeds. They made gardens and grew their vegetables. There was a lake nearby where, you couldn’t catch many, but they would go fishing. The men worked cutting lumber and in Slocan there was a sawmill.

How did you bide your time? Were you given a job?

There were no schools — no teacher would come out there. So, what happened was they asked us, the older ones who had at least a high school education, to teach the younger ones. We taught them from grade one to eight. After I lost my baby they asked me to come and teach. I had never taught before! Well, I knew the director. I told her, “I have no experience!” She said “Oh, you’ll do.”

I had grade one, and it was the most rewarding year I’ve had.

All of these kids were so eager to learn, and every morning there’d be about a half a dozen of them at my door waiting to walk me to school [laughs]. We had no textbooks, no equipment, and these kids had to pass government exams every year. They did very well.

We kept telling the students, “We aren’t always going to be in this situation, so you have to be ready to go out and join the rest of the schools.” They all worked very hard, and we had some marvelous teachers too, because out it came people like David Suzuki — who was in grade two at that time — and Raymond Moriyama, who became a famous architect.

DID YOU KNOW?

The person who asked Pat Adachi to teach in Slocan was Hide Hyodo Shimizu. Shimizu was instrumental in organizing education for interned Japanese Canadian children during the Second World War. For this, she was awarded the Order of Canada in 1982.

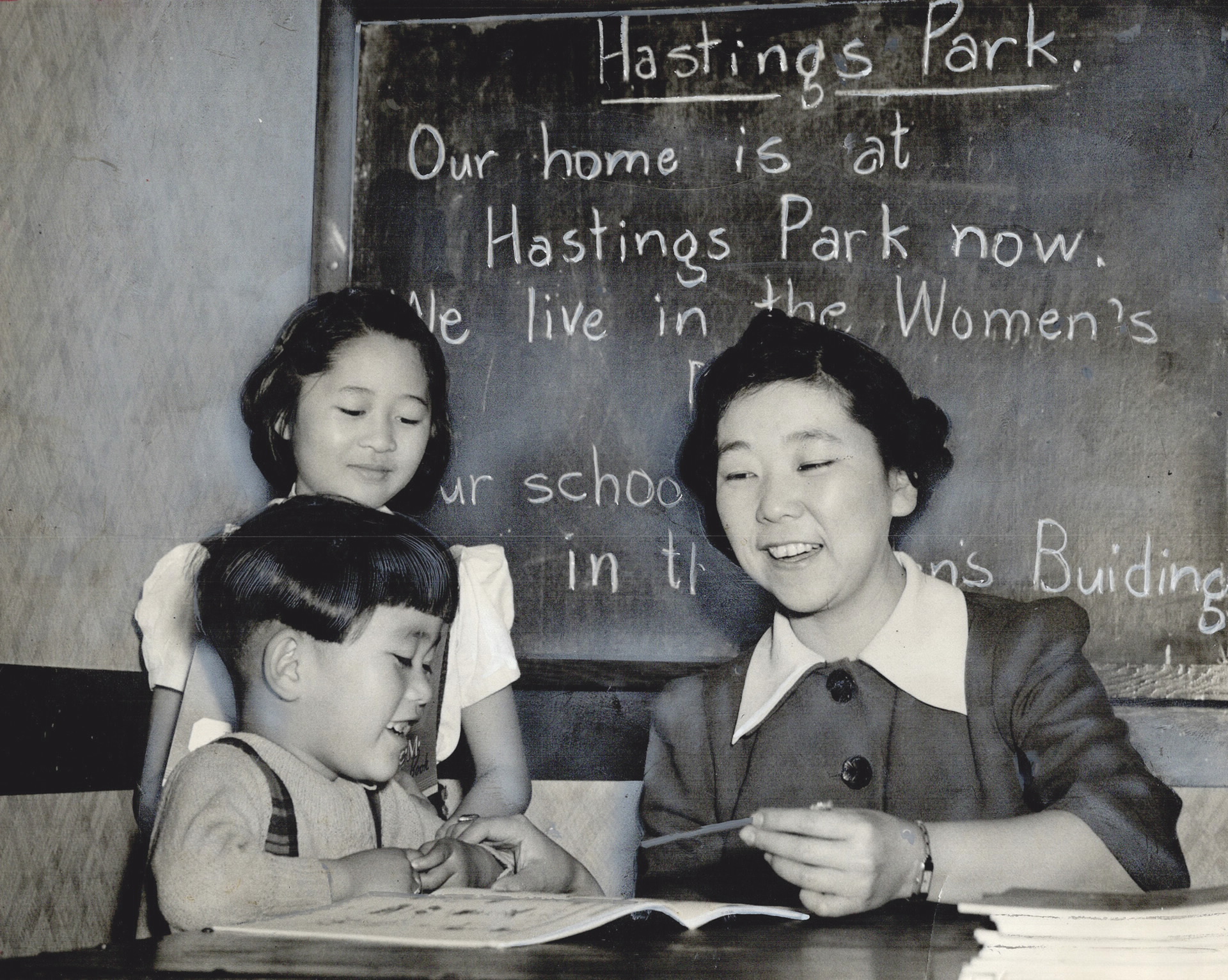

Hide Hyodo teaching children detained at Hastings Park, Vancouver, in 1942. With her are Midori Jane, age 6, and Naomi, age 10.

(courtesy Toronto Star Archives/Toronto Star)

What happened when the war finally ended? How did you go about piecing your lives back together?

Somehow, we lived through it. We were in that ghost town, but they had to do something about us once the war was over. So, they said we had to be re-patriated to Japan. Well, we didn’t know what Japan was. We’d never been there. My father said: “Japan is a defeated country. The people don’t have enough food for themselves, they’re certainly not going to welcome us.”

He said “You were born here, and we’re going to live here. It’s not always going to be like this.”

Some people did go back to Japan. They had aging parents that wanted to die in Japan, and their families would go with them. But the majority of the young people wanted to live in Canada — but you had to go east, or north of the Rockies. We couldn’t go back to Vancouver, but there was nothing there anyways. The government had confiscated and sold it all.

We couldn’t go to Toronto, unless you had someone to sponsor you there, or a place to live, or a job. So, gradually, some people went to Alberta or Manitoba, and a few used to come out east. At first it was the younger boys who went east — many were Asahi boys, although they were older now. Eventually, like if you knew somebody living in Toronto and had a place to go to, you were able to come.

DID YOU KNOW?

In 1992 Pat Adachi wrote the book Asahi: A Legend in Baseball about the team she idolized as a child in Vancouver. In 2017, she was awarded with a Meritorious Service Award from the Governor General for her work documenting and helping to establish a legacy for the Vancouver Asahi and Canada’s Japanese Canadian community.

Is that how you ended up living in Toronto?

My husband and I had a son by that time. He was about six months old. We moved out to a place in Ontario near Fort Frances. It was farming country. Us and another family headed there. We ended up arriving at three o’clock in the morning. They dropped us off at the railroad platform and somebody came to pick us up and took us to this farmhouse. There was no running water, no electricity, and I had a six-month old baby. They finally put running water in, and we lived there, in a one-room shack in the bushes.

During the summer the boys looked after the cattle and in the winter my husband had to go out with his horse and sleigh, and to get pelts. Just himself. If he had an accident, or if anything happened to us, nobody would know.

It’s amazing, you know, how you find friends. We had met some neighbours… people from nearby farms. The Browns had two daughters who were schoolteachers, and a son. They would invite us to Sunday dinner on the weekends. Somehow, they helped us through the winter and we came out in the spring and they said, “We’d never thought you’d make it.” But my husband worked hard, and fortunately nothing happened to us. I guess the fresh air did us good — I gained 30 pounds.

By that time, some friends had moved out to Toronto. They had bought a big house [and] invited us to come, so we were able to move to Toronto.

We decided that we had to find our own place to live; we couldn’t be sponging off our friends.

We had to start from scratch, and somehow managed to get a house. The only people that would help us was the Jewish community, because they had gone through the same problems. We owe them a great deal.

Anyways, there was a Jewish lawyer who found us a house in the Junction [neighbourhood]. It must have been a school at one time. It had three floors, and we found a few desks and chairs that belonged to a school upstairs on the porch. We bought that house and lived on the first floor. My aunt and her family used the front part of the second floor and another family friend lived in the back part. On the third floor there were two couples. That way, somehow we managed to pay the mortgage. Toronto has been our home ever since.

When you tell your story to young adults today — those who would have been your age at the time you were sent to Slocan — what’s their reaction?

The younger generation today would have fought back. They say, “Why didn’t you fight back?”

We were all law-abiding citizens. We always believed that you obeyed the rules…. And that’s the way we were raised.

Share on Facebook

Share on Facebook Share on X

Share on X Share by Email

Share by Email Share on Google Classroom

Share on Google Classroom