The Asahi was a Japanese Canadian baseball club in Vancouver (1914–42). One of the city’s most dominant amateur teams, the Asahi used skill and tactics to win multiple league titles in Vancouver and along the Northwest Coast. In 1942, the team was disbanded when its members were among the 22,000 Japanese Canadians who were interned by the federal government (see Internment of Japanese Canadians). The Asahi were inducted into the Canadian Baseball Hall of Fame in 2003 and the British Columbia Sports Hall of Fame in 2005.

Background: Japanese Migration and Settlement

As early as 1877, Japanese immigrants began to settle in British Columbia, where there existed a breadth of economic opportunity in the fishing, mining and agricultural industries. By 1911, just over 9,000 people of Japanese ancestry (Nikkei) had settled permanently in Canada; 95 per cent lived in British Columbia, with roughly 3,000 in the Vancouver area. The new immigrants, known in the Japanese community as the Issei, mainly hailed from fishing and farming villages on the southern islands of Japan. Many settled in the “Japantowns” of Vancouver and Victoria, on farms in the Fraser Valley and in fishing villages, as well as in pulp-mill and mining towns along the Pacific Coast. Several Nikkei plied their trade as elite boat builders, and by 1900 members of the community held over 40 per cent of British Columbia’s fishing licenses.

Did you know?

Manzo Nagano is the first known Japanese immigrant to Canada. He arrived in BC in May 1877. Like many members of the Japanese community in BC, Nagano’s sons George Tatsuo and Frank Teramuro, enjoyed both playing and watching baseball. Frank played with the Vancouver Asahi, while George was such a big fan of the game that he named his first son after American outfielder Tyrus “Ty” Cobb, one of the greatest players of the era.

Many Issei purchased land on Powell Street in Vancouver’s Downtown Eastside, creating “Little Tokyo.” The neighbourhood flourished with the establishment of the Japanese Methodist Mission (1896), the Vancouver Japanese Language School (1906) and numerous Issei-owned shops and restaurants.

The Issei held their culture in high regard, and while living in an enclave helped preserve Japanese culture and tradition, the necessity for neighbourhood congregation was due to the community’s exclusion from Canadian society. In Vancouver, racial discrimination and racially motivated violence was rampant (see Racism).

Baseball in the Japanese Community

Baseball was a central pastime among Vancouver’s Japanese community and much of the action revolved around the Powell Street Grounds in the heart of Little Tokyo. As amateur teams were formed — among them, the Vancouver Nippon Baseball Club in 1908 — and as the sport grew in popularity in the early 1920s, baseball became a social backdrop for Issei and Nisei (second-generation Japanese Canadian) residents. Many businesses were closed during games, which drew large crowds of fans who elevated Japanese Canadian ballplayers to hero status.

The Vancouver Asahi

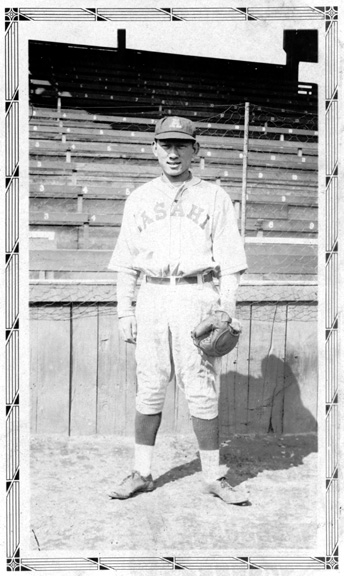

The Vancouver Asahi was officially formed in 1914 by local businessman Matsujiro Miyasaki. The team played out of the Powell Street Grounds (officially called Oppenheimer Park) in Vancouver’s Downtown Eastside. The team’s name means “morning sun” and is similar to the translation of Nihon (Japanese for Japan), “origin of the sun.”

Did you know?

Matsujiro Miyasaki owned a clothing and food store on Powell Street and would feed his players tamago-meshi, a high energy dish of egg on rice prepared at his shop.

Over the years, three brothers, Mickey Kitagawa, Yo Horii and Eddie Kitagawa formed the core of the Asahi along with Yosomatsu Nishizaki. Miyasaki was the team’s first manager and coach. He ran the team until 1917. According to the National Nikkei Museum and Heritage Centre, the Asahi gelled as a club in its first four years by playing teams of “local longshoremen and firefighters, and teams from along the coast and the British Columbia interior.”

When the Vancouver Nippon folded in 1918, the Asahi inherited its top players and became the sole Japanese Canadian baseball team in the city. Maintaining development teams at three different youth levels allowed the Asahi to cultivate talent from within the organization and to sustain a team capable of challenging more established local teams.

The 1919 season culminated in the Asahi’s first major accomplishment: winning the amateur Vancouver International League pennant. It was about this time that the Asahi began to attract players from other Nikkei teams in the surrounding area and its popularity spread beyond the Japanese community. In 1920, for instance, roughly half of the Vancouver senior baseball league’s all-star team was of Japanese heritage.

Vancouver Leagues

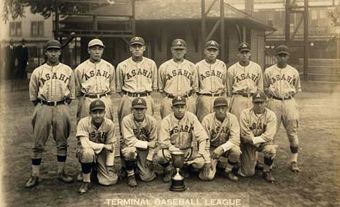

There were many baseball leagues and associations in British Columbia and along the Pacific Coast in the early 20th century. From 1918 to 1919, the Asahi played in the amateur Vancouver International League, where they won the 1919 championship. After one season in the Vancouver City League (1920), the Asahi joined the Vancouver Terminal League in 1921 and played there until 1926.

The Asahi played three rocky seasons in the Vancouver Senior League (1927–29), where they encountered unfair umpiring and teams with ex-pros. The Asahi finished each season they played in the Senior League in last place before returning to the Terminal League in 1930, where they remained until 1935. The following year, they joined the Vancouver Commercial League, followed by the Vancouver Burrard League in 1938, where they remained until the end of the 1941 season. The team was broken up in 1942 when all Japanese Canadians living on the Pacific Coast were interned during the Second World War (see Internment of Japanese Canadians).

Touring

The Asahi played regularly against Nikkei teams from other cities, often travelling across the border to Seattle or Tacoma, Washington. The Pacific Northwest Japanese Baseball Championship grew out of these exhibition games and was first organized in 1928 between 11 Nikkei clubs. The Vancouver Asahi won five-straight titles from 1937 to 1941.

In September 1921, select Asahi and players from other clubs in Vancouver and Seattle formed the Asahi All-Stars and toured Japan. The team played in several venues across Japan against university teams. Remaining Asahi members stayed at home and played as the Asahi Tigers for the 1921 season.

Did you know?

In May 1935, the first professional baseball team in Japan, the Tokyo Giants (now known as the Yomiuri Giants), played the Asahi in a multi-game series at Con Jones Park in East Vancouver. A report in the Sun mentions Reg Yasui, the “clever local backstop and manager of Asahis, who nailed three Tokyo Giants trying to steal second base in the first game of the series.”

“Brainball”

In order to compete in the more talented Terminal League, the team turned to Harry Miyasaki, who was hired as manager in 1922. With Miyasaki, a member of the 1919 championship team, the Asahi found its winning strategy, a style of play that was labelled “brainball” or “smartball” by the Vancouver press.

In the 1920s, baseball was defined by powerful players who drove in runs with big hits and home runs. The opposite of that style, brainball was developed by Miyasaki to counter such power and strength. Composed of players smaller in stature and with less hitting ability, the Asahi built its offensive energy on fundamentals and speed. Essentially a form of “inside baseball,” brainball stressed teamwork and solid execution, employing stolen bases and bunts to get runners into scoring position and to home plate. The team honed these skills with martial discipline. According to the National Nikkei Museum and Heritage Centre:

“Miyasaki made his players practice placing bunts until they could hit them with precision anywhere. Runners would be readied on the bases. ‘Otose’ [‘drop it’ or ‘bunt’] would be yelled out in Japanese. Before the bat touched the ball, they were on the move, primed to score two runs off a single bunt.”

Such hard work and determination paid off: Asahi players often led the league in bunting for hits, reaching first base and stealing. Though it was not the style of play most common in its day, it was highly entertaining and effective. As the Vancouver Sun wrote in 1926, “Miyasaki has drilled into them the fine points of the game and there is no club in local amateur circles that plays more to signals than they do.” In 1928, the team won a game 3–1 without registering any hits, scoring all their runs through sacrifice bunts, walks, base stealing and opposition errors.

Upon mastering Miyasaki’s style of play, the Asahi were able to capture Terminal League titles in 1926, 1930, 1932 and 1933. They followed the same playbook until the team was forced to disband in 1942.

Popularity

The team’s success led to a strong following among Japanese and White fans alike. Some individual players were invited to join all-White teams, as Roy Yamamura did with the top-division Vancouver Arrows in 1931. By the end of the 1930s, the Asahi were one of the most dominant teams in the city, having won a league championship in every year from 1936 to 1941. However, the 1941 Pacific Northwest Japanese Baseball Championship was the last major win for the Asahi.

Racial Discrimination

The primarily Protestant and Caucasian population in Vancouver did not welcome the influx of Japanese immigrants who arrived there at the beginning of the 20th century (see Prejudice and Discrimination). The number of Japanese immigrants allowed to enter the country per year was based on low quotas — 400 persons per year from 1907 to 1928 and 150 per year from 1928 until immigration from Japan was halted in 1940.

During the Great Depression in the 1930s, the provincial government often denied Asian Canadians social assistance and limited the work they could perform: the number of salmon licenses made available to Japanese fisherman, for instance, had been incrementally restricted since the early 1920s; and Japanese loggers were either denied access to logging licenses or had their licenses taken away during the Depression. Each restriction was a means to maintain White dominance of the economy. Additionally, Japanese Canadians were not granted the right to vote until 1948.

Anti-Asian racism came to a boil in 1907 when a mob of White men numbering in the thousands stormed Vancouver's Chinatown and made its way towards the nearby Japanese enclave surrounding Powell Street, ransacking shops and breaking windows along the way. Members of the Japanese community were forced to protect themselves and fight back, restricting the damage caused in Little Tokyo compared with the devastation in Chinatown.

Asahi players were frequent victims of abuse outside of the baseball diamond, but by immersing themselves in baseball, deemed a “White sport,” they were subject to additional displays of racism. On the field, the Asahi were not treated with respect by their competitors. Managers from opposing teams would frequently use racial slurs on the diamond and during games to demean the Asahi. Off the field, the two major newspapers, the Vancouver Sun and the Daily Province, frequently published articles with racist language, such as “Japs,” “Nips” and “Little Brown Men.”

Disbandment and Internment

On 24 February 1942, just 12 weeks after the Japanese attack on Pearl Harbor and Hong Kong, the federal Cabinet used the War Measures Act to order the removal of all Japanese Canadians residing within 160 km of the Pacific Coast. In total, some 22,000 men, women and children of Japanese ancestry — 75 per cent of whom were Canadian citizens — were removed from their homes, farms and businesses and transported to detention centres and work camps.

The interned included current and former members of the Vancouver Asahi, which was forced to disband. Despite being sent to camps across British Columbia, many of the players had brought baseball mitts and Asahi uniforms to the camps with them. In the spring of 1942, Asahi veterans formed teams, built baseball diamonds and played baseball with fellow prisoners and guards. Teams from different camps in the Slocan Valley — including the Lemon Creek All-Stars, coached by Asahi pitcher Ty Suga — were eventually allowed to play one another, their fans following their team to other camps. Teams in the area organized the 1943 Slocan Valley Championship, which was won by the All-Stars. One team, situated in a camp outside of Lillooet and coached by Asahi infielder Kaye Kaminishi, played against residents of the town.

Kaye Kaminishi is the last surviving member of the Vancouver Asahi. Learn more about his life in Vancouver, playing for the Asahi and his internment in the podcast “A Proud Benchwarmer.”

At the end of internment in 1949, the Asahi never reorganized. Many of the players moved throughout the country, with nothing left to return to in Vancouver, where their homes, businesses and personal property had been confiscated and sold by the federal government.

Some of the players from the Asahi youth program went on to form and join new clubs across the country, including the Montreal Nisei Baseball Team (1949 city champions), Vancouver Nisei (1953 city champions) and Honest Ed’s Nisei in Toronto.

Legacy

After internment ended and Asahi team members dispersed across Canada, many never returned to Vancouver, cementing the end of the Asahi playing days. Thirty-one years after their final season, a team reunion was held at the Japanese Canadian Cultural Centre in Toronto in 1972. The event was attended by such prominent players as Roy Yamamura and Ty and Kaz Suga.

In the summer of 2003, the Toronto Blue Jays hosted members of the Asahi during an evening of appreciation for the team, coinciding with its induction into the Canadian Baseball Hall of Fame. Also that year, the National Film Board released an hour-long documentary on the team, Sleeping Tigers: The Asahi Baseball Story. In 2005, the team was inducted into the British Columbia Sports Hall of Fame.

On 26 August 2008, the Asahi were recognized as a National Historic Event by the Government of Canada.

The Canadian Nikkei Youth Baseball Club was established in 2014 and hosted its first annual Asahi Legacy Game. Two years later, the club was renamed the Asahi Baseball Association. The Asahi organizes bi-annual baseball tours to Japan for players aged 13 to 15 and hosts skills training sessions for youth aged 9 to 15.

The Vancouver Asahi, by Japanese director Ishii Yuya, premiered at the Vancouver International Film Festival in September 2014, where it won the top audience award. In 2019, Historica Canada released a Heritage Minute about the Asahi that features Kaye Kaminishi, the last surviving member of the team. That same year, Canada Post released a stamp in honour of the team.

Share on Facebook

Share on Facebook Share on X

Share on X Share by Email

Share by Email Share on Google Classroom

Share on Google Classroom