Oceanography

Oceanography is the branch of earth science (seeGEOLOGY) that studies the OCEANS and seas in all their aspects: the movement and composition of their WATERS; their origin; the evolution of their form; the nature, distribution and interactions of their plant and animal denizens; and their interactions with the atmosphere, which affect climate and weather.Subfields

From descriptive beginnings as the geography of the sea, oceanography has matured into a quantitative and multidisciplinary science bringing together experts from many basic fields. The interconnectedness of marine problems demands from scientists of many disciplines a close collaboration that gives oceanographic research a special flavour. Physical oceanography combines the work of instrument makers who design sophisticated apparatus to measure or sample the corrosive and often inaccessible oceanic medium; analysts and computer specialists who interpret the data; and theoreticians who explain the observed physical properties of the ocean using the physics of rotating fluids. HYDROGRAPHY is an applied branch of physical oceanography concerned with mapping the ocean depths, calculating TIDE tables and producing navigational charts (seeCARTOGRAPHY).

Chemical oceanography studies the composition of seawater; the elements and compounds it holds in solution; their reactions with inert and living matter; and the effects of natural and man-made POLLUTION. Marine geology and geophysics study the origin of ocean basins; the spreading and shrinking of seas through geological ages; the EROSION of shorelines; the evolution of bottom sediments; and the nature and location of sub-bottom mineral resources. BIOLOGICAL OCEANOGRAPHY brings together botanists, zoologists, bacteriologists, FISHERIES experts and other biological specialists in the study of marine life and its harvesting potential. Marine ecology, an important interdisciplinary aspect of oceanography, studies marine ecosystems, their natural fluctuations, their impact on the rest of the ecosphere and their response to anthropogenic disturbances.

Relations to Other Fields

Oceanographers share common theoretical and methodological approaches with researchers working in related areas. For example, oceanography is closely related to limnology, the study of lakes, and physical oceanography has much in common with METEOROLOGY, which studies the motion of another terrestrial fluid, the atmosphere. Oceanographers can also supply important practical data to workers in other fields. For example, ocean engineering combines oceanographic knowledge with engineering techniques in the design and protection of coastal installations and offshore structures; knowledge of ocean currents and properties helps predict fish migrations.

Oceanography in Canada

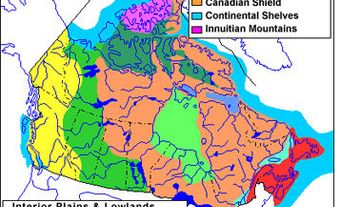

The growth of oceanography in Canada, a country abutting 3 oceans (Atlantic, Pacific and Arctic) and containing large freshwater inland seas, has been continuous for over a century. Oceanography was first applied, in Canada as elsewhere, to problems of navigation. The Canadian Tidal Survey (now the Canadian Hydrographic Service) was formed in 1893. Under the leadership of its first director, William Bell DAWSON, it started its work of compiling marine charts and measuring currents and sea levels, a task that rapidly transcended its purely practical goals. Hydrography is the progenitor of physical oceanography. In the same period a board of management for fisheries and marine research was established under the Department of Naval Service. The board was superseded by the Biological Board of Canada (later the FISHERIES RESEARCH BOARD of Canada).

Although biological oceanography originated, in part, in the practical concerns of fisheries, it received much of its life breath from the scientific interest generated by voyages of discovery in the second half of the 19th century, especially the CHALLENGER EXPEDITION (1872-76). The expedition, briefly operating out of Halifax for some of its North Atlantic work, pioneered deep-sea dredging for marine organisms. During the late 19th century, marine research laboratories proliferated in Europe and the US. Two marine stations were established in Canada in 1908, at St Andrews, NB, and Nanaimo, BC, under the impetus and direction of Edward E. PRINCE. These establishments, formally under the direction of the federal Department of Fisheries, were given a broad mandate to study not only fish, but also the plants, chemistry and motions of the ocean.

Under the direction of the Fisheries Research Board of Canada, the Atlantic and Pacific biological stations were for decades focal points of Canadian oceanography, mapping fisheries resources and water properties, mounting deep-sea expeditions and providing expertise for Canadian participation in international bodies. On the Atlantic coast, fisheries oceanographers Archibald G. HUNTSMAN and Louis Lauzier participated in the description of local waters and in the work of the International Commission for North Atlantic Fisheries; William Ford led Canadian participation in the study of the Gulf Stream during Operation Cabot in 1950.

In the Pacific John P. TULLY and his colleagues in Nanaimo pioneered the study of FJORDS and participated (with the US and Japan) in the North Pacific expeditions that mapped the ocean habitat of salmon. The waters of the ARCTIC ARCHIPELAGO were also explored; in the East, the Calanus expeditions (1948-79) led by Maxwell DUNBAR of McGill University investigated Hudson Bay and its approaches; in the West, William M. CAMERON played a leading role in the joint Canadian-US expeditions to the Beaufort Sea in the early 1950s.

Following World War II, defence research laboratories in Canada and elsewhere rapidly became interested in physical oceanographic problems such as ocean wave forecasting and ocean acoustics. In the late 1940s and the 1950s, the need for professional oceanographers led to the foundation of graduate research and teaching institutes at the universities of British Columbia, Dalhousie and McGill. The spread of oceanographic studies to academic institutions continued in the 1960s with the creation of the Groupe interuniversitaire de recherches océanographiques du Québec by Laval, Université de Montréal and McGill, and with the establishment of teaching and research laboratories at Université du Québec à Rimouski. All are now in the research group Québec-Océan. Oceanographic studies are also offered at the universities of Victoria, Guelph and Memorial.

A major development in Canadian oceanography was the concentration and significant expansion, through the 1960s and 1970s, of research and service operations run by the federal government through the Department of Fisheries and Oceans (now Fisheries and Oceans Canada) in 2 large institutions: the BEDFORD INSTITUTE OF OCEANOGRAPHY in Dartmouth, NS, and the Institute of Ocean Sciences (IOS) in Sidney, BC. These are comparable in scale to other major oceanographic research centres of the world, housing hundreds of scientists concerned with all aspects of marine science. Additional laboratories of the department include the Institut Maurice Lamontagne (Mont-Joli, Qué), and the Northwest Atlantic Fisheries Centre (St John's, Nfld). A central information storage and dissemination agency (the Marine Environmental Data Service) is based in Ottawa. Fisheries laboratories in Nanaimo and St Andrews have become more specialized in fish-stock management.

The HUDSON 70 EXPEDITION accomplished the first complete circumnavigation of the Americas, taking a group of University of British Columbia oceanographers led by George L. PICKARD on the first scientific survey of the fjords of southern Chile, and a team from the Bedford Institute, led by Cedric R. MANN, who made deep-flow measurements through Drake Passage, south of Cape Horn.

The Canadian Coast Guard operates Canada's oceanographic fleet, which includes a few medium-sized, deep-sea vessels (eg, the Parizeau, Hudson andJohn P. Tully) and smaller vessels for hydrographic and coastal work.

Manned research submersibles of the PICES series, constructed in North Vancouver and used for many years by Canadian researchers, have been replaced by the more flexible deep-diving remotely operated vehicle ROPOS, used, for example, in deep-visual exploration of hot vents on Juan de Fuca ridge off Canada's West Coast. Although Canadian vessels are used mainly for within Canada's exclusive economic zone (ie, 200-mile fishing zone), occasional long-range cruises take Canadian oceanographers to remote seas.

REMOTE SENSING by aircraft and satellite plays an increasing role in ocean monitoring. Air and satellite-mounted, multispectral radiometers are used for accurate mapping and identification of nearshore features. The advent of satellite navigation and altimetry has led to centimetre-accuracy positioning in the horizontal and vertical directions, which is a great help to hydrography and current measurements. Canada's Radarsat allows viewing of some ocean features and sea ice even under cloudy skies (seeSATELLITE, ARTIFICIAL).

Ocean observatories - arrays of fixed instruments reporting to shore stations through fiber-optic cable networks - allow oceanographers to monitor ocean phenomena directly and continuously. A small array has been deployed in the eastern Gulf of St Lawrence off Bonne Bay, Nfld; another one is under development off Victoria (the VENUS project) and will serve as a pilot for NEPTUNE, a more ambitious plan to monitor the Juan de Fuca plate. NEPTUNE will link instruments monitoring sea-floor motions, hydrothermal activity, ocean currents and fish movements off the southern BC coast. A specialized system of acoustic receivers, the POST (Pacific Ocean Sound Tracking) array is also in place to track salmon migrating along the BC coast.

Research

Practical challenges facing Canadian oceanography include fisheries management and the complex interactions between its scientific and socioeconomic aspects; problems of nearshore pollution and deep-ocean dumping; understanding the impacts of global CLIMATE CHANGE on Canada's oceans; improved understanding of SEA ICE conditions for purposes of navigational safety and offshore operations; exploitation of offshore petroleum and mineral resources on the Canadian continental shelves; and development of instruments for in-situ and remote sampling of the ocean to gather the information necessary to tackle the above problems. Expeditions by the Canadian SOLAS (Surface Ocean-Lower Atmosphere Studies) group in the North Pacific and North Atlantic are examples of leading Canadian participation in fundamental ocean climate problems.

The arctic regions continue to be an area of special concern. In the early 1970s joint government and industry surveys of the BEAUFORT SEA paved the way for current hydrocarbon exploration. A few years later, the Eastern Arctic Marine Environmental Studies program gathered extensive baseline information about marine ecosystems and circulation patterns in Baffin Bay, Lancaster Sound and adjacent passages. Geophysical and oceanographic expeditions to the deep Arctic Ocean north of the archipelago, such as the Lomonosov Ridge Experiment (LOREX, 1979) and the Canadian Expedition to Study the Alpha Ridge (CESAR, 1983), have confirmed Canada's interests in the High North. More recently, the Canadian Arctic Shelf Exchange Study (CASES, 2000-04) of the oceanography of the eastern Beaufort Sea and the Amundsen Gulf and the creation of ArcticNet, a multidisciplinary, Canada-wide centre of excellence, have added considerable impetus to ARCTIC OCEANOGRAPHY.

The history of seafloor spreading and its relation to the formation of deep-sea mineral deposits are also of great interest. In Canada seafloor spreading occurs off the BC coast at the Juan de Fuca and Explorer ridges. Here are submarine mountain chains where new ocean floor is continually being created. Rich mineral deposits have already been discovered, partly through Canadian participation in the International Ocean Drilling Program (see OCEAN MINING; PLATE TECTONICS).

International Cooperation

Because the ocean knows no political boundaries, Canada must collaborate with other countries in learning about the oceans and managing marine resources. Canada is thus a member of many international scientific organizations such as the International Council for the Exploration of the Sea and the North Pacific Marine Science Organization. Canadian oceanographers also participate in the elucidation of fundamental problems of a global nature, such as the role played by the oceans in climate change (through the international Geosphere-Biosphere Program).

Two areas of particular interest have been the oceans' capacity for holding in solution much of the carbon dioxide released by the burning of fossil fuels (the subject of the Joint Global Ocean Flux Study) and the role of marine organisms in regulating the fluxes of greenhouse gases across the ocean-atmosphere interface (through the Surface Ocean-Lower Atmosphere Study). A detailed understanding of oceanic dynamics is still incomplete, although much progress was made during the World Ocean Circulation Experiment (1990-2002), in which Canada was a major player, and the prediction of oceanic variability will not be achieved until a more intimate knowledge of ocean currents is attained and supported by a dense network of observation stations. This task will occupy physical oceanographers for years to come.

Canadian oceanographers are active in international programs dedicated to improving the understanding of oceanic circulation such as the ARGO system of free-drifting buoys and the CLIVAR (Climate Variability) program of research on ocean and atmosphere variability.

Societies and Journals

Of the more than 1000 oceanographers in Canada, most work for the federal or provincial governments, a few teach in universities, and an increasing number are employed by the private sector to help in offshore exploitation and nearshore engineering and pollution problems. The Canadian Meteorological and Oceanographic Society, the principal professional society of oceanographers in Canada, gathers together mainly physical and chemical oceanographers. It publishes a quarterly journal of scientific research, Atmosphere-Ocean, and a bulletin of news and articles of general information. It also holds an annual scientific congress. Another Canadian research publication devoted mainly to fisheries science is the monthly Canadian Journal of Fisheries and Aquatic Sciences, published by the National Research Council.

Share on Facebook

Share on Facebook Share on X

Share on X Share by Email

Share by Email Share on Google Classroom

Share on Google Classroom