Pitikwahanapiwiyin (Poundmaker), Cree chief (born circa 1842 in central SK; died 4 July 1886 in Blackfoot Crossing, AB). Remembered as a great leader, Pitikwahanapiwiyin strove to protect the interests of his people during the negotiation of Treaty 6. Considered a peacemaker, he did not take up arms in the North-West Resistance. However, a young and militant faction of his band did participate in the conflict, resulting in Pitikwahanapiwiyin’s arrest and imprisonment for treason. His legacy as a peacemaker lives on among many Cree peoples, including the Poundmaker Cree Nation in Saskatchewan.

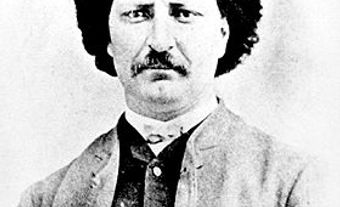

Cree chief Pitikwahanapiwiyin (Poundmaker).

Early Life

Pitikwahanapiwiyin was born to a Métis woman and a Stoney shaman named Sikakwayan. His family lived among the Plains Cree peoples in what is now Saskatchewan, under the leadership of his uncle, Chief Mistawasis (Big Child). (See also Plains Indigenous Peoples in Canada.)

Pitikwahanapiwiyin’s status in his community was heightened after a battle between the Cree and Siksika (Blackfoot) in 1873. During this battle, the son of Siksika chief Isapo-Muxika (Crowfoot) was killed. Isapo-Muxika adopted Pitikwahanapiwiyin as a means of replacing his fallen son and gave him the Siksika name Makoyi-koh-kin (Wolf Thin Legs).

After the battle, Pitikwahanapiwiyin stayed with his adopted father at Blackfoot Crossing for a while before returning to his own people. Now regarded as the son of a powerful chief and bringing home with him horses (a sign of wealth) from his new Siksika family, Pitikwahanapiwiyin’s influence among his own people — the Cree — grew. Pitikwahanapiwiyin’s adoption served to bolster bonds of friendship between longstanding enemies, the Siksika and Cree nations.

Treaty 6

In August 1876, Pitikwahanapiwiyin was a Cree band leader or minor chief and was present at the negotiations of Treaty 6 in Fort Carlton. (See also Numbered Treaties.) Pitikwahanapiwiyin did not believe that the terms of the treaty were favourable to his people and therefore was opposed to signing the agreement. He questioned how the government, by way of a treaty, could lay claim to their territory: “This is our land. It isn’t a piece of pemmican to be cut off and given in little pieces back to us. It is ours and we will take what we want” (See also Indigenous Territory).

Outranked and outvoted by other Cree chiefs present at Fort Carlton, Pitikwahanapiwiyin eventually but reluctantly signed Treaty 6. Two years later, and now a chief, Pitikwahanapiwiyin and his people moved onto a reserve along Battle River, about 64 km west of Battleford.

Cree Gathering, 1884

Life on the reserve was difficult; rations of food and supplies promised by the government in the treaty were inconsistent or insufficient. This led to unrest among some of Pitikwahanapiwiyin’s people, particularly the young warriors. Seeking to come up with a plan of action, Pitikwahanapiwiyin and his fellow Cree leaders, such as Chief Mistahimaskwa (Big Bear), assembled at Pitikwahanapiwiyin’s reserve in June 1884. They held a thirst dance (also known as a sun dance) as a means of gaining spiritual strength.

The North-West Mounted Police (NWMP) disrupted the thirst dance, looking for a participant accused of assaulting John Craig, a farm instructor on a nearby reserve. Reinforced by 90 men, the police demanded Pitikwahanapiwiyin and Mistahimaskwa hand over the suspect. The chiefs refused, but in the end, the accused was arrested. Nevertheless, Pitikwahanapiwiyin and Mistahimaskwa successfully avoided a large-scale, armed conflict between their warriors and the NWMP.

North-West Resistance

Discontent with settler-colonists was spreading across the Prairies, particularly among young First Nations and Métis peoples. By 1885, on the eve of the North-West Resistance, the population of Pitikwahanapiwiyin’s band had grown to accommodate some of these warriors. While Pitikwahanapiwiyin himself always advocated for peace, some members of his band thought otherwise.

Attack on Battleford Village

After the Métis won the Battle of Duck Lake on 26 March 1885, most of the white settlers sought shelter in NWMP camps near Battleford. Pitikwahanapiwiyin travelled there to meet with the local Indian agent, seeking to collect rations he was owed. However, the agent refused to help him because he was afraid to leave the police-protected area. This angered Pitikwahanapiwiyin’s warriors. Despite their chief’s calls for peace, the young warriors took revenge by raiding the town. The following day, these men established a warrior’s lodge east of Cut Knife Creek. While Pitikwahanapiwiyin remained chief, the true authoritative power was vested in the lodge.

Battle of Cut Knife

Lieutenant-Colonel William Dillon Otter’s force of 325 armed men arrived at Battleford to exact revenge on Pitikwahanapiwiyin’s band. The plan was to attack their camp near Cut Knife Hill. However, having received news of their arrival, Cree and Stoney warriors set out to defend their camp against Otter’s men. The battle lasted approximately seven hours, after which Otter’s forces withdrew. Pitikwahanapiwiyin did not participate in the Battle of Cut Knife, but he managed to prevent more bloodshed by convincing the warriors not to chase after Otter’s army.

Battle of Batoche

Though Pitikwahanapiwiyin was against it, his warriors planned to join Louis Riel’s Métis forces at Batoche. On route, they captured a wagon train carrying supplies for Colonel Otter’s forces. The warriors took the men from the supply train as prisoners. Not wanting bloodshed, Pitikwahanapiwiyin intervened to ensure that the prisoners were not harmed.

When he heard that the Métis had been defeated at Batoche, Pitikwahanapiwiyin sent Robert Jefferson, his farming instructor, to tell Major-General Frederick Dobson Middleton that he was ready to talk peace. Jefferson did as he was asked and returned with a message from Middleton: surrender unconditionally. On 26 May 1885, Pitikwahanapiwiyin and some of his councillors went to Battleford where they were arrested.

Trial and Imprisonment

Put on trial in Regina in July 1885, Pitikwahanapiwiyin protested his innocence, telling the court that he did “everything [he] could do… to stop bloodshed.” However, the court still found him guilty of treason and sentenced him to three years in prison. He served one year in Stony Mountain Penitentiary in Manitoba before he was released.

Death

Poor in health and broken in spirit, Pitikwahanapiwiyin went to visit his adopted father, Isapo-Muxika (Crowfoot), on the Siksika reserve after his release from prison. Shortly thereafter, Pitikwahanapiwiyin died of unknown causes. Some say that he died of a lung hemorrhage, possibly due to complications with tuberculosis, which he may have contracted in prison. Others contend that he died of a stroke or heart attack.

Reclamation of Artifacts

Following the North-West Resistance in 1885, many of Pitikwahanapiwiyin’s possessions were housed in museums across Saskatchewan, as well as abroad, such as in London, England. In July 2017, the federal government loaned some of Pitikwahanapiwiyin's belongings, including a ceremonial war club, to the Poundmaker Cree Nation museum, located on the Poundmaker reserve in Saskatchewan. Some Indigenous peoples see this as the beginning of efforts to repatriate similar items housed abroad or outside the traditional territories of the Indigenous nations involved. (See also Repatriation of Artifacts.)

Petition for Exoneration

For years, leaders of the Poundmaker Cree Nation sought to exonerate their chief for his conviction of treason-felony after the North-West Resistance. In 2017, the Assembly of First Nations and Saskatchewan’s Federation of Sovereign Indigenous Nations announced that they had passed a resolution to support such a campaign. A petition was circulated that year asking the federal government to clear Pitikwahanapiwiyin’s name and to recognize him as a peacemaker. There have been similar efforts to exonerate Cree chiefs Mistahimaskwa and Kapeyakwaskonam (One Arrow), who were also convicted of treason, despite having not participated in the resistance. In January 2018, the Government of Canada announced its intention to “move forward with Poundmaker Cree Nation to develop a joint statement of exoneration for Chief Poundmaker.”

Exoneration

On 23 May 2019, Canadian prime minister Justin Trudeau visited Poundmaker Cree Nation on behalf of the federal government to officially exonerate Chief Poundmaker for the crime of treason-felony during the North-West Resistance of 1885. Trudeau’s statement of exoneration was co-developed with Poundmaker Cree Nation and included a formal apology “on behalf of the government of Canada and all Canadians.” The Prime Minister stated that Chief Poundmaker was a “peacemaker,” a man who “worked tirelessly to ensure the survival of his people.” Finally, Trudeau added these words: “I am here today on behalf of the Government of Canada to confirm without reservation that Chief Poundmaker is fully exonerated of any crime or wrongdoing.”

Significance

Chief Poundmaker was one of the great leaders of his people. He strove to protect the interests of the Cree during the negotiation of Treaty 6 and acted as a peacemaker during the North-West Resistance of 1885. Poundmaker’s conviction, imprisonment, and early death was a profound loss to his people. Blair Stonechild, a Professor of Indigenous Studies at the First Nations University of Canada in Regina, argued that Chief Poundmaker “was essentially the rising leader of the Cree.” His early death was “a tremendous, tremendous loss.”

In May 2019, Milton Tootoosis, Headman and Councillor of Poundmaker Cree Nation, said that “losing someone like him would be like losing someone like the Dalai Lama or Gandhi.” Tootoosis hoped that Poundmaker’s exoneration would be the first step towards a better future: “My hope and I think many leaders’ hope, is that we will learn from these mistakes and accept the truth that this happened so that we can move forward together in a positive way.”

Share on Facebook

Share on Facebook Share on X

Share on X Share by Email

Share by Email Share on Google Classroom

Share on Google Classroom