Prohibition in Canada came about as a result of the temperance movement. It called for moderation or total abstinence from alcohol, based on the belief that drinking was responsible for many of society’s ills. The Canada Temperance Act (Scott Act) of 1878 gave local governments the “local option” to ban the sale of alcohol. Prohibition was first enacted on a provincial basis in Prince Edward Island in 1901. It became law in the remaining provinces, as well as in Yukon and Newfoundland, during the First World War. Liquor could be legally produced in Canada (but not sold there) and legally exported out of Canadian ports. Most provincial laws were repealed in the 1920s. PEI was the last to give up the “the noble experiment” in 1948.

The Temperance Campaign

Prohibition was the result of generations of effort by temperance workers to close bars and taverns. They were seen as the source of much misery in an age before social welfare existed. Temperance activists and their allies believed that alcohol, especially hard liquor, was an obstacle to economic success; to social cohesion; and to moral and religious purity.

The main temperance organizations were the Dominion Alliance for the Total Suppression of the Liquor Traffic and the Woman’s Christian Temperance Union. The newsletter of the latter was the Canadian White Ribbon Tidings. The Temperance struggle was connected to other reform efforts of the time, such as the women’s suffrage movement. It was also motivated in part by Social Gospel beliefs.

19th Century Prohibition

Various pre-Confederation laws against the sale of alcohol had been passed, including the Dunkin Act in the Province of Canada in 1864. It allowed any county or municipality to prohibit the retail sale of liquor by majority vote. In 1878, this “local option” was extended to the whole Dominion under the Canada Temperance Act, or Scott Act.

By 1898, the temperance forces were strong enough to force a national plebiscite on the issue. But the government of Sir Wilfrid Laurier decided that the majority of 13,687 votes cast in favour of prohibition was not large enough to warrant passing a law; especially since Quebec had voted overwhelmingly against it. Much of the country was already “dry” under local option. Full provincial bans would eventually emerge.

Wartime Sacrifice

Prohibition was first enacted on a provincial basis in Prince Edward Island in 1901. It became law in the remaining provinces — as well as in Yukon and in Newfoundland (which did not join Confederation until 1949) — during the First World War. Prohibition was widely seen at the time as a patriotic duty and a social sacrifice, to help win the war. (See also Wartime Home Front.)

Unlike in the United States, banning booze in Canada was complicated by the shared jurisdiction over alcohol-related laws between Ottawa and the provinces. The provinces controlled sales and consumption. The federal government oversaw the making and trading of alcohol. (See Distribution of Powers.) In March 1918, Ottawa stopped, for the remainder of the First World War, the manufacture and importation of liquor into provinces where purchase was already illegal.

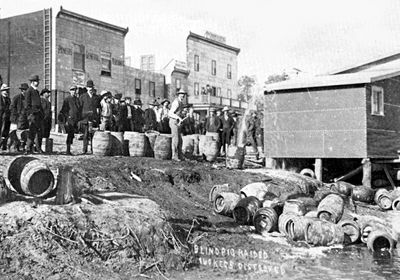

Blind Pigs and Rum Running

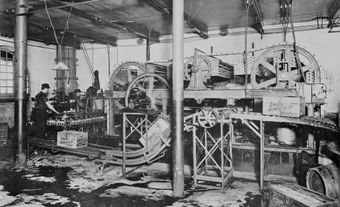

Provincial temperance laws varied. In general, they closed legal drinking establishments and forbade the sale of alcohol as well as its possession and consumption; except in a private dwelling. In some provinces, domestic wines were exempt. Alcohol could be purchased through government dispensaries for industrial, scientific, mechanical, artistic, sacramental and medicinal uses. Distillers and brewers and others properly licensed could sell outside the province.

Although enforcement was difficult, drunkenness and associated crimes declined significantly. However, illicit stills and home-brewed “moonshine” proliferated. Much inferior booze hit the streets. But good liquor was readily available, since its manufacture was permitted after the war. Bootlegging (the illegal sale of alcohol as a beverage) rose dramatically; as did the number of unlawful drinking places known as “speakeasies” or “blind pigs.” One way to drink legally was to be “ill,” since doctors could give prescriptions to be filled at drugstores. Abuse of this system resulted, with veritable epidemics and long queues occurring during the Christmas holiday season.

A dramatic aspect of the prohibition era was rum running. By constitutional amendment, the United States was under even stricter prohibition from 1920 to 1933 than was Canada. The manufacture, sale, and transportation of all beer, wines, and spirits were forbidden there. Liquor could, however, be legally produced in Canada (but not sold there) and legally exported out of Canadian ports. This created the odd situation of allowing smugglers to leave Canada with shiploads of alcohol destined for their “dry” neighbour, under the protection of Canadian law. Smuggling, often accompanied by violence, erupted in border areas and along the coasts. Political cartoons in newspapers showed leaky maps of Canada with Uncle Sam attempting to stem the tide of alcohol.

Repeal of Prohibition Laws

Prohibition was too short-lived in Canada to engender any real success. Opponents maintained that it violated British traditions of individual liberty; and that settling the matter by referendum or plebiscite was a departure from Canadian parliamentary practice. Quebec rejected it as early as 1919 and became known as the “sinkhole” of North America. Tourists flocked to “historic old Quebec” and the provincial government reaped huge profits from the sale of booze.

In 1920, British Columbia voted to go “wet.” By the following year, some alcoholic beverages were legally sold there and in Yukon through government stores. Manitoba inaugurated a system of government sale and control of alcohol in 1923, followed by Alberta and Saskatchewan in 1924; Newfoundland in 1925; Ontario and New Brunswick in 1927; and Nova Scotia in 1930. The last bastion, Prince Edward Island, finally gave up “the noble experiment” in 1948. Pockets of dryness under local option continued for years throughout the country.

See also Temperance Movement in Canada; Distilling Industry; Seagram; Brewing Industry in Canada; Wine Industry; Craft Brewing in Canada; Cannabis Legalization in Canada.

Share on Facebook

Share on Facebook Share on X

Share on X Share by Email

Share by Email Share on Google Classroom

Share on Google Classroom