Simon Girty, frontiersman, British Indian agent, Loyalist settler in Upper Canada (Ontario), (born 14 November 1741 near Harrisburg, Pennsylvania; died 18 February 1818 in Malden, Upper Canada). Girty fought in the American Revolution and in wars involving Indigenous peoples and white settlers. Girty had a great capacity to work with Indigenous leaders but was often remembered as a villain and controversial figure, mainly because of his allegiance to Britain, rather than to the Americans.

Early Life

The son of an American trader also named Simon, and his wife Mary, Girty grew up in the American colonies during tumultuous times. In 1750, his father was killed in a fight with another settler. In 1756, after the capture of Fort Granville during the Seven Years' War between France and Britain, Girty was taken prisoner by Indigenous people and adopted by Onöndowa’ga (Seneca) chief Guyasuta. For the next eight years, Girty lived as an Onöndowa’ga in what is now New York State. He became an expert woodsman, and although illiterate, had a natural ability for learning languages. He became fluent in at least nine Indigenous languages.

Fort Pitt

In 1764, Girty was sent to Fort Pitt (Pittsburgh) as part of a general release of white captives by Indigenous groups. He worked as a guide and interpreter, and engaged in business with influential merchants Alexander McKee and Matthew Elliott. Girty was distrusted in the white community because of his Indigenous associations. However, McKee, an agent of the British Indian Department, found Girty to be a skilled diplomat and interpreter in negotiations with the various First Nations.

Girty established such a high level of trust among Indigenous leaders that he was one of the few white people permitted to speak in tribal councils. In 1774, as an officer of the British colonial militia, Girty was instrumental in bringing an end to a minor war between settlers and the Indigenous chiefs Logan and Cornstalk, in the frontier of what is now West Virginia and Kentucky.

American Revolution

At the outbreak of the American Revolution in 1776, Girty served the Americans as a scout and interpreter. But due to both his association with supporters of the British side such as McKee and Elliott, and his affinity toward Indigenous people, Girty was regarded with suspicion. He also became convinced that if the Americans were victorious, they would seize all tribal lands in the Ohio Valley. In March 1778, Girty, McKee and Elliott fled to the British stronghold of Detroit. Girty switched allegiances in the war and became an agent of the British Indian Department. Officially he was an interpreter, but his duties would be much more far-reaching.

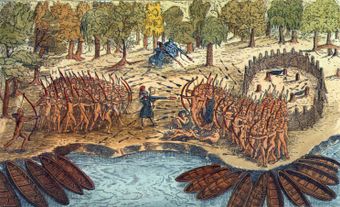

Girty travelled throughout the lands of the various First Nations, urging leaders to ally themselves with the British. He carried out spy missions in American territory, and fought in numerous raids and battles. In June 1780, Girty was with British Captain Henry Bird’s force of regular soldiers and Indigenous warriors at the capture of Ruddle’s Station and Martin’s Station in Kentucky.

One of Girty’s duties as a British agent was to ensure that Indigenous warriors treated American prisoners humanely and took them alive to Detroit. In this he was largely successful. Many American captives, including famed frontiersman Simon Kenton, later said that they owed their lives to Girty. Girty also rescued Catharine Mallot from captivity during the war, and married her.

But Girty was unable to save the life of American Colonel William Crawford in the final months of the war. Crawford was captured when Indigenous warriors routed his army at the Battle of Sandusky in June 1782. Despite Girty’s protests at the execution site, the warriors burned Crawford at the stake in revenge for the earlier massacre of an Indigenous community at Gnadenhutten by American militia.

In August that year, a British-Indigenous force led by Girty and Captain William Caldwell defeated a column of Kentucky militia at the Battle of Blue Licks, one of the last engagements of the American Revolution.

Loyalist

After the British surrender, Girty joined the movement of Loyalists migrating from the former American colonies to British North America. He homesteaded on a farm at Malden in Upper Canada, and continued to support Indigenous resistance to American westward expansion. As part of this, he participated in the defeats of United States generals Josiah Harmar (1790) and Arthur St. Clair (1791) by Indigenous forces. He retired to Canada permanently, after US General Anthony Wayne’s decisive victory over the Indigenous side brought the Ohio frontier conflict to an end at the Battle of Fallen Timbers in 1794.

Girty was too old to fight in the War of 1812, and fled before an advancing American army in 1813. Five years later, he died at his home of natural causes, and was buried with military honours.

Legacy

Girty was a figure of almost supernatural fear to Americans during and after the American Revolution, but stories of his alleged cruelty were based almost entirely on knowledge of Crawford’s terrible fate. A highly embellished account of Crawford’s death, written by American journalist Hugh Henry Brackenridge, became a sensation that firmly established Girty’s reputation as the “White Savage.”

Girty is portrayed as a villain in romantic American novels and in Stephen Vincent Benet’s The Devil and Daniel Webster (1937). He was the model for Sampson Gattrie in John Richardson’s novel The Canadian Brothers (1840).

Share on Facebook

Share on Facebook Share on X

Share on X Share by Email

Share by Email Share on Google Classroom

Share on Google Classroom