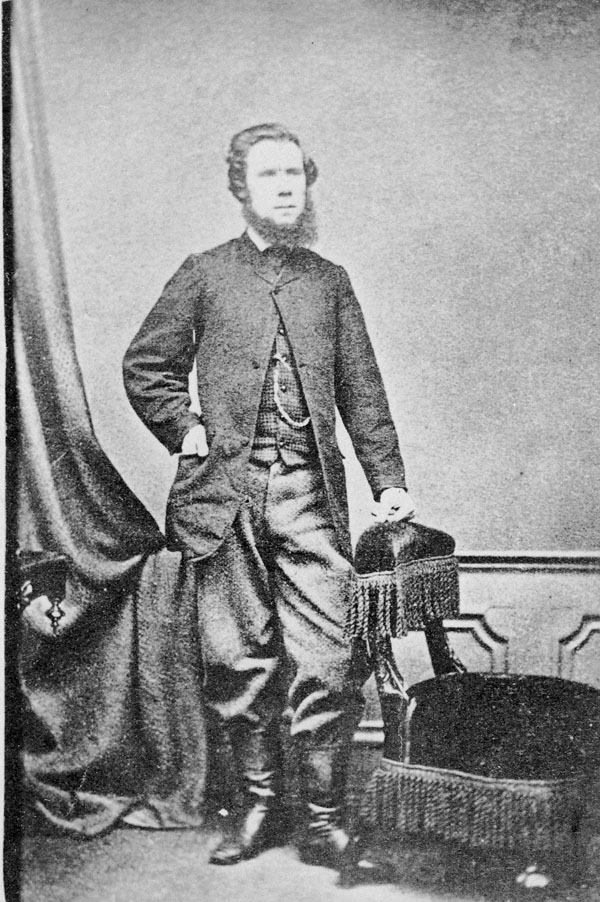

Within 24 hours, the police were sure they had their man. Acting on a tip, they went to the hotel room of a tailor named Patrick James Whelan. They searched his belongings and found copies of a revolutionary Irish American newspaper and membership cards of Irish Canadian organizations that included many Fenians. They also found a Smith & Wesson revolver that had apparently been fired the previous day.

After Whelan was brought into custody, more damning evidence rapidly accumulated. Several witnesses testified that he had repeatedly talked about assassinating McGee, that he had made threatening gestures to McGee in the House of Commons, and that he had been stalking McGee before the murder. A few days later, a lumberjack by the name of Jean-Baptiste Lacroix said that he had seen Whelan shoot McGee. Shortly afterwards, a detective with the Grand Trunk Railway, Reuben Wade, claimed that he had overheard Whelan and a group of conspirators plotting to kill McGee. Meanwhile, a policeman and a fellow prisoner who were eavesdropping near his prison cell reported that Whelan bragged about what a “great fellow” he was for shooting McGee. By the time Whelan went to trial in September, the case against him seemed airtight.

In one of the many ironic twists that run through Irish Canadian history, the chief prosecutor at the trial was James O’Reilly. He was an Irish Catholic who excluded fellow Catholics from the jury. The defence was led by John Hillyard Cameron. He was a former Grand Master of the Orange Order and one of the best lawyers in the country.

Step by step, Cameron began to poke holes in the prosecution’s case. Whelan’s membership in Irish Canadian organizations and his choice of newspapers were irrelevant to the case, he argued. The judge agreed. Cameron also attempted to discredit a key witness who had recounted Whelan’s threats against McGee. Many people had made threatening remarks against McGee, Cameron pointed out. This did not make them murderers.

The most effective part of the defence, though, was Cameron’s cross-examination of Lacroix, who claimed to have witnessed the killing. Cameron showed that Lacroix had gotten his descriptions of Whelan and McGee all wrong. He had also been unable to identify Whelan in the prison until the authorities assisted him. It seemed clear that Lacroix was either hopelessly incompetent or lying for the reward money.

Almost as implausible was Reuben Wade’s claim to have overheard Whelan plotting to assassinate McGee. It was unlikely that a group of conspirators would have discussed their plans in front of a complete stranger. Nor could Whelan’s supposed prison boast about killing McGee be taken at face value. Even if his words were accurately reported (which was not at all clear), their tone could well have been ironic. This left the critical question of the gun. Cameron produced a witness who said that she had accidentally fired Whelan’s gun several weeks before the assassination. She even showed the powder burns on her arm to prove it. This, Cameron argued, explained why the gun looked as if it had been recently fired.

As the jury deliberated, they decided to dismiss Lacroix’s testimony. But the forensic evidence that Whelan’s gun had been fired, together with the circumstantial evidence that Whelan had been threatening and stalking McGee, proved decisive. On 15 September 1868, he was found guilty and sentenced to death. (See also: Capital Punishment.)

Right up to the moment of his execution, Whelan insisted he was innocent. How much truth was there in this? On the one hand, the prison authorities tried to stack the evidence against him. There were also some procedural irregularities in the trial itself. On the other hand, the circumstantial evidence against Whelan was very strong, despite the defence’s arguments to the contrary. The condition of the gun was consistent with a recent firing. Forensic tests conducted in 1973 indicated that the fatal bullet was compatible with both the gun and the bullets that Whelan owned. (The bullet that killed McGee was found lodged in the door frame of his home.) Although Whelan denied that he was the hit man, he said just before his death that he knew the identity of the killer, and that he was present when McGee was assassinated. This of course would have made him guilty as an accessory.

The balance of probabilities suggests that Whelan either shot McGee or was part of a hit-squad. But there is still room for reasonable doubt as to whether he was the man who actually pulled the trigger.

Share on Facebook

Share on Facebook Share on X

Share on X Share by Email

Share by Email Share on Google Classroom

Share on Google Classroom