Background

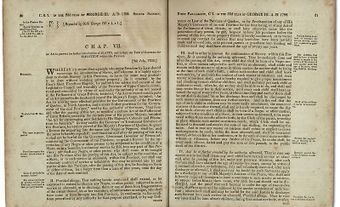

The Fugitive Slave Act, first passed by the federal government 4 February 1793, gave slaveholders the right to recover escaped enslaved persons. While federal authorities could execute the Act, states were not compelled to enforce it. Many Northern states disregarded the law. Abolitionists in the North circumvented the law through the operation of the Underground Railroad. Some states implemented Personal Liberty Laws to hamper enforcement and gave fugitives the right of trial by jury to appeal decisions ruled against them. In some states, fugitives on trial received legal representation. The new 1850 bill strengthened the enforcement measures of the 1793 version of the Fugitive Slave Act to appease Southern slaveholders who were threatening to secede from the United States in order to protect their interest in enslavement. The Act allowed for the pursuit and capture of enslaved persons anywhere in the United States, including in the Northern states where enslavement had been abolished.

The Act made it illegal for individuals to aid escaping slaves with food, shelter, money or any other forms of assistance at a penalty of up to six months in jail and a fine of $1,000. Anyone who obstructed federal agents or deputized citizens from recovering fugitives could also be charged. The federal law required that all citizens assist slave owners in capturing their runaway slaves.

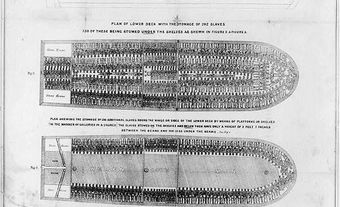

Alleged fugitives were denied the right to defend their case with a jury trial. Special federal commissioners were appointed to handle cases. The Act made more federal agents available for enforcement, and agents were compelled to arrest suspected runaway slaves or face a $1,000 fine. To encourage agents to enforce the law, they were entitled to a recovery fee, influencing many to abduct, by any means, Black persons (free or otherwise) and sell them to slave traders or slaveholders. Free Blacks were in jeopardy of being kidnapped and sold into slavery in the South without recourse. As a result, many freedom-seekers risked their lives in pursuit of freedom in Canada, where enslavement had been abolished with the 1834 Slavery Abolition Act.

Impact

Based on available census figures and documented testimonies, historians have tried to calculate the number of African Americans who entered Canada. While estimates vary, historian Fred Landon approximated that between 1850 and 1860, an estimated 15,000 to 20,000 African Americans settled in Canada, increasing the Black population to about 60,000. Many escapees made the dangerous journey on their own, while others received assistance from the Underground Railroad.

Several prominent cases filed under the Fugitive Slave Act ended in Canada. Anthony Burns, a fugitive from Virginia living in Boston, Massachusetts, was arrested and convicted under the Fugitive Slave Act in May 1854. He was sentenced to return to his master in Virginia — a ruling that incited protest among Black and white abolitionists in the city. Following his return to Virginia, he was sold to another slave holder in North Carolina. But within a year, his freedom was purchased with money raised by a Black church he attended in Boston. Burns moved to Ohio and attended Oberlin College, and in 1861 he relocated to St. Catharines, Canada West, where he served as minister for Zion Baptist Church until his death in 1862. Burns was the last person to be tried under the Fugitive Slave Act in Massachusetts.

Shadrach Minkins also escaped enslavement in Virginia and reached Boston in 1850. He was held under the Fugitive Slave Act after federal agents posed as customers at the coffee shop where he was employed and arrested him 15 February 1851. At his trial, Black and white abolitionists of the Boston Vigilance Committee forcibly removed Minkins from the court house and moved him to Montreal by way of the Underground Railroad.

In 1852, a freedom-seeker named Joshua Glover found asylum in Racine, Wisconsin, but was soon tracked down by his owner. While he was detained, a group of abolitionists stormed the jailhouse and helped Glover escape to Canada via the Underground Railroad. He settled in the Toronto area after finding employment with Thomas and William Montgomery in the village of Lambton Mills in York Township (Etobicoke).

Building Communities in Canada West

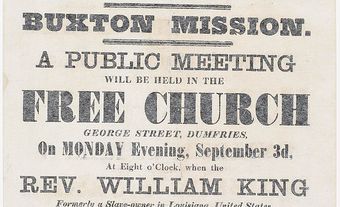

Black communities developed in Niagara Falls, Buxton, Chatham, Owen Sound, Windsor, Sandwich (now part of Windsor), Hamilton, London and Toronto as well as in other regions of British North America such as New Brunswick and Québec. All of these locations were terminals on the Underground Railroad.

Many African American immigrants wanted to live close to one another for support and for security against slave catchers. The Chatham Vigilance Committee was formed by concerned Black residents in order to protect fugitives from being returned to enslavement in the United States. The Fugitive Slave Act resulted in several illegal attempts to kidnap refugees in Canada and return them to former owners in Southern states. As reported by Mary Ann Shadd Cary in The Provincial Freeman, in September 1858, over 100 armed Black men and women rescued a teenage boy named Sylvanus Demarest when a man who claimed to be his owner put him on a train to take him to the US. They were spotted in London, Canada West, by Elijah Leonard, the former mayor of the town, who asked a Black porter to send a telegraph message ahead to Chatham so that members of the Vigilance Committee could intervene. Demarest was saved. He lived with the Shadd family for a short time before moving to Windsor.

Legacy

The Fugitive Slave Act sparked the largest migration wave of African Americans into Canada in the 19th century. The self-emancipated men and women who settled in Canada continued to fight against enslavement in the US after their successful flight, and engaged in various abolitionist activities. Many assisted incoming escapees by providing them with food, shelter, clothing and employment. Recently liberated Blacks formed and joined benevolent organizations and anti-slavery societies. Some settlers went on missions across the border to help rescue freedom-seekers and bring them to Canada.

Two anti-slavery newspapers were published in Canada West. Abolitionist Henry Bibb, once enslaved in Kentucky, founded the Voice of the Fugitive in Sandwich (now a suburb of Windsor) in 1851, Canada’s first Black newspaper. The Provincial Freeman was founded in Windsor in 1853 by Samuel Ringgold Ward, another fugitive turned abolitionist, alongside Mary Ann Shadd who took over the editorial role following year. Both newspapers reported on safe arrivals via the Underground Railroad, reported on what was happening in the US in regards to enslavement, and notified the community about potential threats to their freedom. The Black press was also used to mobilize the public against the practice of enslavement and encouraged political activism and community-building initiatives.

In September 1851, members of Canada West’s Black community organized the North American Convention of Coloured People at St. Lawrence Hall. Fifty-three delegates from the United States, England and Canada gathered in Toronto because it was determined that it would be the safest location for a large meeting where the main discussions were the abolition of African American enslavement, improving the quality of life for Blacks in North America, and encouraging enslaved people to run away. The three day convention was chaired by Henry Bibb, J. J. Fisher, Thomas Smallwood and Josiah Henson, all freedom-seekers living in Canada West. The meeting closed with the decision that the best place for people of African descent (those wishing to flee enslavement, as well as free Blacks) to live in North America was Canada, because of its security and promises of freedom and opportunity.

Share on Facebook

Share on Facebook Share on X

Share on X Share by Email

Share by Email Share on Google Classroom

Share on Google Classroom