Many important medical discoveries and advancements that have improved and saved the lives of people around the world have been made by Canadians and Canadian research teams. Treatments and technologies, some of which are still used today, are the result of their research and experimentation. This list overviews a few of the life-saving medical contributions made in Canada.

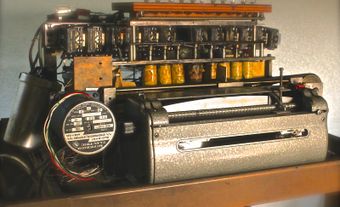

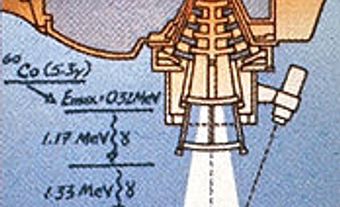

1. Cobalt-60 Radiation Therapy

By the 1940s, cancer mortality rates in Canada were soaring. The disturbing trend and the availability of new technology led Dr. Harold Elford Johns, machinist John MacKay, and four graduate students, including Sylvia Olga Fedoruk, to work together at the University of Saskatchewan to develop a way to better treat cancer. They built a machine that directed a beam of radioactive Cobalt-60 into a patient’s body, which could kill cancerous tumours without hurting the skin. Its first success was celebrated in November 1951 when the so-called “Cobalt Bomb” effectively treated a Saskatoon woman’s cervical cancer. The treatment was globally adopted and it dramatically increased the survival rates of millions of cancer patients.

2. Montreal Procedure

Dr. Wilder Graves Penfield was born in Spokane, Washington. He became an internationally respected neurosurgeon who devoted much of his career to studying epilepsy, a brain condition that causes a person to suffer seizures. (See also Neuroscience.) In 1928, he began to work at Montreal’s Royal Victoria Hospital where, in 1934, he founded the Montreal Neurological Institute. Penfield’s work mapped the brain and advanced knowledge in many related disciplines. He developed the “Montreal Procedure,” a new surgical method that enabled the removal of cells from the brain that caused epilepsy. Dr. Penfield and his colleagues published their findings in 1952. The Montreal Procedure was adopted around the world.

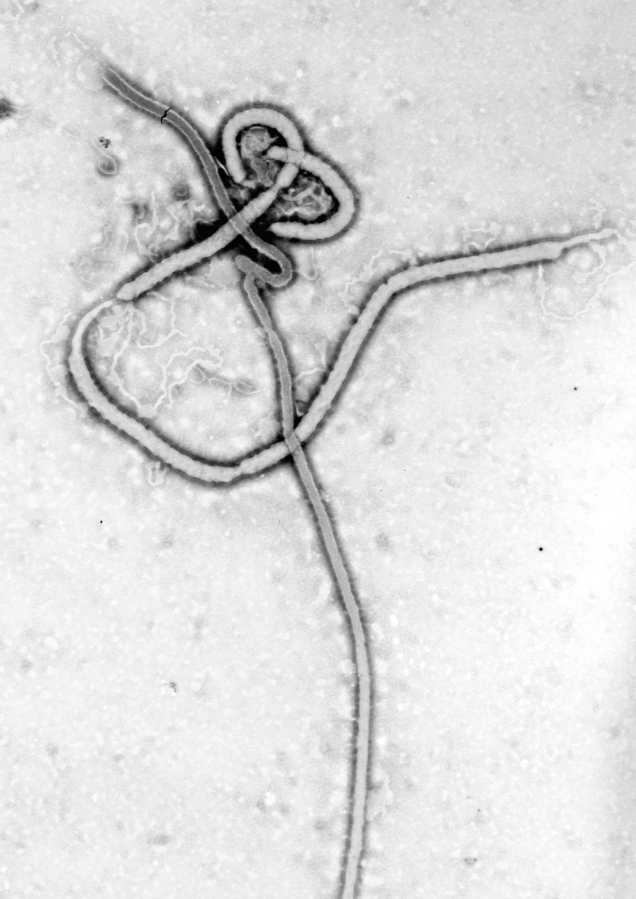

3. Ebola Vaccine

Ebola virus disease (EVD) is a contagious virus that first appeared in Africa in 1976. On average, Ebola has an approximate fatality rate of 50 per cent, but fatality rates reached as high as 90 per cent during past outbreaks. As the number of Ebola cases rose each year, more scientists sought for a way to treat or prevent the virus. In 2005, Dr. Judie Alimonti, an immunologist, accepted a position with the Public Health Agency of Canada (PHAC) in Winnipeg. From 2010 to 2015, Alimonti led an initiative to develop an Ebola vaccine. Canada donated the vaccine to the World Health Organization. Its use in Africa, Europe, and elsewhere has saved countless lives.

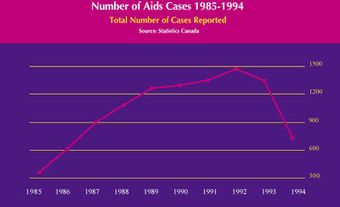

4. HAART

In the early 1980s, cases of Acquired Immune Deficiency Syndrome (AIDS) were rising and, by the 1990s, millions of people were infected and dying. Dr. Julio Montaner, originally from Argentina, became a post-doctoral fellow at the University of British Columbia in 1981. Six years later, Dr. Montaner became the university’s director of the AIDS Research Program and the Infectious Disease Clinic. He co-organized the 1996 Vancouver International AIDS Conference where he presented research on Highly Active Antiretroviral Therapy (HAART). This treatment allowed those with HIV/AIDS to live with and manage their disease by combining three or more medications. HAART is now used throughout the world.

5. Childproof Caps

In 1957, Dr. Henri J. Breault was appointed chief of pediatrics and director of the Poison Control Centre at the Hôtel-Dieu Hospital in Windsor, Ontario. He was appalled that every year over 1,000 children in Windsor were falling ill, and at least one child died, due to ingesting medications and household hazardous products. Breault began seeking a bottle cap that young children would be unable to open. He eventually worked with Peter Hedgewick, president of the Reflex Corporation near Windsor. In 1966, Hedgewick’s team developed a cap, which would be known as the Palm-N-Turn, that could only be opened by pushing down while turning. Childproof caps were soon widely adopted and they continue to save children from accidental poisoning.

Share on Facebook

Share on Facebook Share on X

Share on X Share by Email

Share by Email Share on Google Classroom

Share on Google Classroom