This article is one of four that surveys the history of the film industry in Canada. The entire series includes: Canadian Film History: 1896 to 1938; Canadian Film History: 1939 to 1973; Canadian Film History: 1974 to Present; Canadian Film History: Notable Films and Filmmakers 1980 to Present.

See also: Quebec Film History: 1896 to 1969; Quebec Film History: 1970 to 1989; Quebec Film History: 1990 to Present; 30 Key Events in Canadian Film History; Exhibit Eh: Canadian Film History in 10 Easy Steps; Documentary Film; Canadian Film Animation; Experimental Film; Film Distribution; Top 10 Canadian Films of All Time; English Canadian Films: Why No One Sees Them; National Film Board of Canada; Telefilm Canada; Canadian Feature Films; Film Education; Film Festivals; Film Censorship; Film Cooperatives; Cinémathèque Québécoise; The Craft of Motion Picture Making.

Film Cooperatives, Funding Agencies and the Growth of Regional Cinema

Beginning in the early 1970s, regional film cooperatives — such as the Toronto Filmmakers Co-op (1971–79), the Atlantic Filmmakers Cooperative in Halifax (1974–) and the Winnipeg Film Group (1974–) — began to train young filmmakers who remained committed to the concept of a cultural cinema. From the early 1980s to the late 1990s, a generation of talented independent filmmakers began to emerge. They were aided by the introduction in the mid-1980s of provincial funding agencies.

Ontario

In 1986, the Ontario Film Development Corporation (OFDC) opened its doors. The OFDC rejected the export product model of the tax shelter era. Instead, it supported emerging writer-directors with distinctive personal visions. It had an immediate success with Patricia Rozema’s I’ve Heard the Mermaids Singing (1987). It won the Prix de la Jeunesse at the Cannes Film Festival and became an international critical darling.

The OFDC became a model for other provincial agencies that followed its lead. A newfound confidence led to a wealth of low-budget independent productions from across the country. This was a significant development. Previously, production had largely been limited to the metropolitan centres of Montreal and Toronto, with a few notable exceptions. Now, production emerged from every region of the country.

British Columbia

Sandy Wilson had a hit in New York with My American Cousin (1985), a charming coming-of-age story set in BC’s Okanagan Valley in the 1950s. She followed it with its less successful sequel, American Boyfriends (1989), and the country western focused Harmony Cats (1992). Wilson’s features, following on the heels of Phillip Borsos’s The Grey Fox (1982), did much to inject new energy into the domestic Vancouver film scene. Patricia Gruben, an experimental filmmaker of considerable originality, found success with three idiosyncratic features: Low Visibility (1984), Deep Sleep (1990) and Ley Lines (1993).

Other prominent female filmmakers emerged with their own distinctive visions. Mina Shum’s delightful Double Happiness (1994) captured the dilemma of a young Chinese-Canadian woman (Sandra Oh) trying to escape the traditions of her conservative family. Talented newcomer Lynne Stopkewich managed a highly successful adaptation of a Barbara Gowdy short story with her debut feature, Kissed (1996). The dark romance focusing on the love life of a young necrophiliac (Molly Parker) caused a sensation at both the Sundance Film Festival and the Toronto International Film Festival.

Also in Vancouver, John Pozer made a highly original debut feature, the offbeat The Grocer's Wife (1991), followed by The Michelle Apartments (1995). Since the mid-1990s, Vancouver’s Bruce Sweeney established himself with an impressive body of work dealing with contemporary male-female relationships. These included Live Bait (1995), Dirty (1998), Last Wedding (2001), American Venus (2007), Excited (2009) and Kingsway (2018). Carl Bessai directed an average of a film a year through the 2000s, including the family-dynamics trilogy Mothers & Daughters (2008), Fathers & Sons (2010) and Sisters & Brothers (2011).

Prairie Provinces

The Prairies were also witness to a number of highly engaging films. Most prominently, Anne Wheeler debuted with her powerful family drama, Loyalties (1986). She followed it with Bye Bye Blues (1989), a whimsically sentimental tale about a singer (Rebecca Jenkins) making her way during the Second World War, as well as The War Between Us (1995), Better Than Chocolate (1999) and Suddenly Naked (2001). In the 1990s, Gary Burns emerged from Calgary with a trio of edgy suburban comedies: The Suburbanators (1996), Kitchen Party (1998) and waydowntown (2000).

Perhaps the most original production emanated from Winnipeg Film Group alumni. After getting their feet wet in short films, they graduated to the longer form. John Paizs led the way with the critically praised but seldom seen Crime Wave (1985). But it was Guy Maddin who created an international reputation. His highly individualistic style combines silent movie conventions, ironic humour and a postmodern taste for the incongruous. His most notable films include Tales from the Gimli Hospital (1988), Archangel (1990), the brilliant Careful (1992), Twilight of the Ice Nymphs (1997), the widely heralded short film The Heart of the World (2000), The Saddest Music in the World (2004), My Winnipeg (2007), Keyhole (2011) and The Forbidden Room (2015). This remarkably coherent body of work has earned Maddin an international cult following.

Atlantic Canada

From the East Coast, the most singular vision belongs to William D. MacGillivray. He consistently draws on his Nova Scotia roots and explores the relationship between art and life. His first drama was the hour-long Aerial View (1979). It was a prelude to the more ambitious studies undertaken in the feature films Stations (1983), Life Classes (1987), Vacant Lot (1989) and Understanding Bliss (1990). MacGillivray explored similar themes in the documentaries I Will Make No More Boring Art (1988), For Generations to Come (1994), Reading Alistair MacLeod (2005), The Man of a Thousand Songs (2010), about folk singer Ron Hynes, and Danny (2015), about former Newfoundland premier Danny Williams.

Mike Jones, based in St. John’s, drew on a comic tradition of local humour in The Adventures of Faustus Bidgood (1986) and Secret Nation (1992). Accomplished playwright Daniel MacIvor made several successful forays into feature filmmaking. He wrote Wiebke von Carolsfeld’s Marion Bridge (2002) and Bruce McDonald’s Trigger (2010) and Weirdos (2017). He also wrote and directed Past Perfect (2002) and Wilby Wonderful (2004). Another filmmaker of note in the region is Paul Donovan. He carved out a successful career by making a number of more commercially oriented comedies such as Buried on Sunday (1993) and Paint Cans (1994).

Quebec

Quebec cinema emerged from the doldrums of the late 1970s and early 1980s with Gilles Carle’s Maria Chapdelaine (1983). Denys Arcand rocketed to international attention with the acclaimed The Decline of the American Empire (1986) and Jésus de Montréal (1989), both of which earned Oscar nominations for Best Foreign Language Film. He won that award in 2004 for Les invasions barbares (2003). (See also: Top 10 Canadian Films of All Time.)

Other old guard directors who created notable work during this period include Jacques Leduc (Trois pommes à côté du sommeil, 1988; La vie fantôme, 1992), André Forcier (Kalamazoo, 1988; Une histoire inventée, 1990; Le vent du Wyoming, 1994) and Anne Claire Poirier (Tu as crié/Let Me Go, 1997). Veteran theatre director Robert Lepage also made a well-received transition into cinema with Le Confessionnal (1995) and Le Polygraphe (1996). He followed those successes with Nô (1998), La face cachée de la lune (2003) and Triptyque (2013).

Also in the 1980s, Quebec saw the emergence of a number of promising new directors: Micheline Lanctôt (L'homme à tout faire, 1980; Sonatine, 1984; Deux actrices, 1993; Le piège d'Issoudun, 2003; Pour l’amour de Dieu, 2011); Paule Baillargeon (Le cuisine rouge, 1980; Sonia, 1986; Le Sexe des étoiles, 1993); Yves Simoneau (Pouvoir intime, 1981; Dans le ventre du dragon, 1989; Perfectly Normal, 1991); Léa Pool (Anne Trister, 1986 ; À corps perdu, 1988; Mouvements du désir, 1994; Emporte-moi/Set Me Free, 1999; Maman est chez le coiffeur, 2008; La passion d’Augustine, 2015); Pierre Falardeau (Elvis Gratton, 1985; Octobre, 1994; 15 février 1839, 2001); and Jean-Claude Lauzon, who directed two films of audacious quality (Un zoo, la nuit, 1987; Léolo, 1992) before dying in a plane crash in 1997.

The late 1990s saw the rise of commercial cinema in Quebec. The hockey comedy Les Boys (1997) became the biggest domestic hit in Canadian film history, grossing over $6 million, almost exclusively in Quebec. It was followed by the equally successful

sequels Les Boys II (1998) and Les Boys III (2001), as well as such box office hits as Jean-François Pouliot’s La grande séduction/Seducing Dr. Lewis (2003).

During the 1990s, a new generation of directors arose who pursued personal and bold formal innovations. They include: François Girard (Thirty T wo Short Films About Glenn Gould, 1993; The Red Violin, 1998; Silk, 2007; Hochelaga, Terre des Âmes, 2017); André Turpin (Zigrail, 1995; Cosmos, 1996; Un crabe dans la tête, 2001; Endorphine, 2015); Robert Morin (Requiem pour un beau sans coeur, 1993; Windigo, 1994; Quiconque meurt, meurt à douleur, 1998; Le nèg’, 2002; Journal d’un cooperant; 2010; and Les 4 soldats, 2013); Manon Briand (2 secondes, 1998; La turbulence des fluides, 2002; Liverpool, 2012); and most notably the innovative and original Denis Villeneuve (Cosmos, 1996; Un 32 août sur terre, 1998; the multiple Genie Award-winning Maelström, 2000 and Polytechnique, 2009; the Oscar nominated Incendies, 2010; and the psychologically surreal Enemy, 2013, which won multiple Canadian Screen Awards).

Also of note is Bernard Émond, a trained anthropologist who began making documentaries in the early 1990s (Ceux qui ont le pas léger meurent sans laisser de traces, 1992; L'instant et la patience, 1994; Le Temps et le lieu, 2000). He then wrote and directed several acclaimed fiction films that examine the existential crisis of contemporary Western values (La Femme qui boit, 2001; 20h17 rue Darling, 2003; La Neuvaine, 2005; Contre toute espérance, 2007; La Donation, 2005; Tout ce que tu possèdes, 2012).

Other Quebec filmmakers who stood out in the early 21st century are: Philippe Falardeau (La moitié gauche du frigo, 2000; Congorama, 2006; C'est pas moi, je le jure!, 2008; the Oscar-nominated Monsieur Lazhar, 2011; Guibord s’en va-t-en guerre, 2015); Catherine Martin (Mariages, 2001; Océan, 2002; Dans les villes, 2006; Trois temps après la mort d’Anna, 2010; and Une jenue fille, 2013); François Delisle (Le bonheur est une chanson triste, 2004; Toi, 2007; Le météore, 2013; Chorus, 2015); Rafaël Ouellet (Le cèdre penché, 2007; New Denmark, 2009; Camion, 2012); Stéphane Lafleur (Continental – un film sans fusil, 2007; En terrains connus, 2011; Tu dors Nicole, 2014); Anne Émond (Nuit #1, 2011, winner of the Canadian Screen Award for Best First Feature; Les êtres chers, 2015; Nelly, 2016; Jeune Juliette, 2019); Simon Lavoie (Laurentie, 2011; Le torrent, 2012; Ceux qui font les révolutions à moitié n'ont fait que se creuser un tombeau, 2016; La petite fille qui aimait trop les allumettes, 2017); Mathieu Denis (Laurentie, 2011; Corbo, 2014; Ceux qui font les révolutions à moitié n'ont fait que se creuser un tombeau, 2016); and Chloé Robichaud (Sarah préfère la course, 2013; Pays, 2016).

Xavier Dolan emerged as the most talented Canadian filmmaker in recent memory with his award-winning autobiographical directorial debut, J'ai tué ma mère (2009). He followed that with the sensuously cinematic Les amours imaginaires (2010), Laurence Anyways (2012), Tom à la ferme (2013), and the multiple award-winning Mommy (2014) and Juste la fin du monde (2016). Rivalling Dolan’s art-house credibility and film festival accolades is Denis Côté. He focuses on narrative experimentation and attempts to destabilize the viewer’s expectations. His work includes: États nordiques (2005), Elle veut le chaos (2008), Curling (2010), Vic + Flo ont vu un ours (2013), Boris sans Béatrice (2016) and Répertoire des villes disparues (2019).

(See also: Quebec Film History: 1970 to 1989; Quebec Film History: 1990 to Present.)

Far North

In the North, noted soapstone carver Zacharias Kunuk of Igloolik, Nunavut (then Northwest Territories) turned to filmmaking in the late 1980s. He founded the video co-op Igloolik Isuma Productions in 1988 with Norman Cohn, Paul Apak Angilirq and Pauloosie Qulitalik. Kunuk blended documentary and fiction in several acclaimed videos and the 13-episode Nunavut series (1993–95). He then directed Atanarjuat (The Fast Runner) (2001), the first feature-length fiction film made by Inuit in the Inuktitut language. It won worldwide acclaim, including the coveted Camera d’Or at the Cannes Film Festival and six Genie Awards including Best Picture. (In 2015, it was ranked as the best Canadian film of all time.) Kunuk followed that success with The Journals of Knud Rasmussen (2006), the inventive remake Searchers (2016) and One Day in the Life of Noah Piugattuk (2019).

Meanwhile, actor turned writer-director Madeline Ivalu, who appeared in Atanarjuat and The Journals of Knud Rasmussen, made her feature directorial debut with Le jour avant le lendemain (2008). It was named Best Canadian First Feature Film at TIFF and Best Film at the American Indian Film Festival. She followed it with Uvanga (2013).

Toronto New Wave

When it comes to English Canadian cinema, Toronto still provides the critical mass. A large group of Toronto-based filmmakers, informally known as the Toronto New Wave, emerged along with Atom Egoyan in the mid-1980s. Rather than an expression of a particular group aesthetic, Toronto New Wave is a catchphrase for a spirited generation of English-Canadian filmmakers. Most were graduates of film departments at the University of Toronto, Sheridan College or Ryerson Polytechnic University (now Ryerson University). They generally gravitated to LIFT (Liaison of Independent Filmmakers of Toronto), a funky film co-op founded by a group including Bruce McDonald and Peter Mettler. It succeeded the Toronto Filmmakers Co-op.

Patricia Rozema achieved great initial success with her acclaimed debut feature, I’ve Heard the Mermaids Singing (1987). She followed it with White Room (1990), When Night Is Falling (1995), Mansfield Park (1999) and Into the Forest (2015). Bruce McDonald tapped into his interest in rock ‘n’ roll to create the rambunctious Roadkill (1989), Highway 61 (1991), Hard Core Logo (1996), Trigger (2010), This Movie is Broken (2010) and Hard Core Logo 2 (2012), along with the quieter Dance Me Outside (1994), The Tracey Fragments (2007), Pontypool (2008), The Husband (2013) and Weirdos (2016). Peter Mettler, a highly gifted cinematographer, moved with equal ease between fiction, documentary and experimental film. While a student at Ryerson, he directed the surprisingly achieved Scissere (1982). He followed it with The Top of His Head (1989), Tectonic Plates (1992), Picture of Light (1994), Gambling, Gods and LSD (2002) and The End of Time (2012). Jeremy Podeswa made an impressive debut with Eclipse (1994), while Darryl Wasyk provided audiences with a harrowing portrait of the drug world in H (1990). Don McKellar, who had written Roadkill and Highway 61 with Bruce McDonald, had his own auspicious feature directorial debut with Last Night (1998). He followed it with Childstar (2004), the remake The Grand Seduction (2013) and his 2018 adaptation of Joseph Boyden’s Through Black Spruce.

Three major events of the 1980s proved to be instrumental to the growth of this new breed of English Canadian filmmakers. In 1984, the Toronto Festival of Festivals (now the Toronto International Film Festival) launched the Perspective Canada program, the world’s largest international platform for Canadian cinema. In 1986, the Ontario government created the Ontario Film Development Corporation (OFDC). And in 1988, Norman Jewison founded the Canadian Film Centre (CFC). Its graduates began to produce an impressive body of work by the mid-1990s. Don McKellar developed the script for François Girard’s innovative and highly-acclaimed Thirty Two Short Films About Glenn Gould (1993). David Wellington directed two polished features: I Love a Man in Uniform (1993); and a beautifully realized adaptation of the Stratford production of Eugene O'Neill's Long Day's Journey Into Night (1996). John Fawcett had a cult hit with the inventive teen horror move Ginger Snaps (2000). Vincenzo Natali’s debut, Cube (1997), produced through the CFC’s Feature Film Project, broke box office records for a Canadian film in Japan and grossed $15 million in France.

Significantly, a cinema emerged in the 1990s that began to reflect the diverse ethnicity of the country. Atom Egoyan focused on his Armenian heritage with Calendar (1993) and Ararat (2002). Sturla Gunarsson returned to his native Iceland to shoot Beowulf & Grendel (2005). Srinivas Krishna drew on his Indian roots in the carnivalesque Masala (1991). His second film, Lulu (1996), centred on a Vietnamese refugee. Deepa Mehta also delved into her Indian background with Sam and Me (1990), Fire (1996), Earth (1998), Bollywood/Hollywood (2002), the Oscar-nominated Water (2005) and the Salman Rushdie adaptation Midnight’s Children (2012). The latter two are set entirely in India. Black filmmakers also began making films that spoke to their experiences. Clement Virgo directed the highly accomplished Rude (1995). He following it with Love Come Down (2001), Poor Boy's Game (2007), and the miniseries adaptation of Lawrence Hill’s The Book of Negroes (2016). After making a number of acclaimed short films, Charles Officer made an impressive feature debut with Nurse.Fighter.Boy (2008). He followed it with the documentaries Mighty Jerome (2010), about sprinter Harry Jerome, Unarmed Verses (2017) and Invisible Essence: The Little Prince (2018).

While various forms of ethnic cinema flourished, gay filmmakers also came to the fore in the 1990s. John Greyson, a CFC graduate who began his career in video, quickly established himself as one of Canada’s most original talents. He followed his impressive short film, The Making of “Monsters” (1991), with some highly innovative work, most notably the AIDS musical Zero Patience (1993), Lilies (1996) and The Law of Enclosures (2001). Halifax-based Thom Fitzgerald broke through with his gay-themed The Hanging Garden (1998). Underground filmmaker Bruce LaBruce also made a distinctive contribution. He delved into the gay porn underground scene with No Skin off My Ass (1990), Super 8½ (1994), Hustler White (1996), The Raspberry Reich (2004) and L.A. Zombie (2010).

(See also: Canadian Film History: 1974 to Present.)

David Cronenberg and Atom Egoyan

The two most important English Canadian filmmakers, from different generations, are David Cronenberg and Atom Egoyan. Cronenberg acts as both a mentor and an example. He proved that Canadian filmmakers could stay in Canada, make the films they wanted to make and become major players on the international scene. Furthermore, he did this without compromising his vision. Indeed, if anything, his work became more personal as his growing reputation allowed him to investigate his most personal fears.

Cronenberg transitioned from experimental features in the 1960s (Stereo, 1968; and Crimes of the Future, 1969) to commercial films in the science-fiction and horror genres (Shivers, 1975; Rabid, 1976; The Brood, 1979; Scanners, 1980; and Videodrome, 1981) and finally to adaptations of work by other artists (The Dead Zone, 1983; The Fly, 1987; Dead Ringers, 1988; Naked Lunch, 1991; M. Butterfly, 1993; Crash, 1996; and Spider, 2003). His career constitutes a remarkably cohesive perspective on several key themes: fear of the destructive power of the mind and the fragility of the body; a pervasive paranoia about scientific notions of progress; and a fascination with sexuality and gender. Cronenberg has branched out into more conventional subject matter with A History of Violence (2005), based on an American graphic novel, Eastern Promises (2007), his Russian gangster film set in London, A Dangerous Method (2011), about the inner workings of Sigmund Freud and Carl Jung, and Cosmopolis (2012), his adaptation of the Don DeLillo novel.

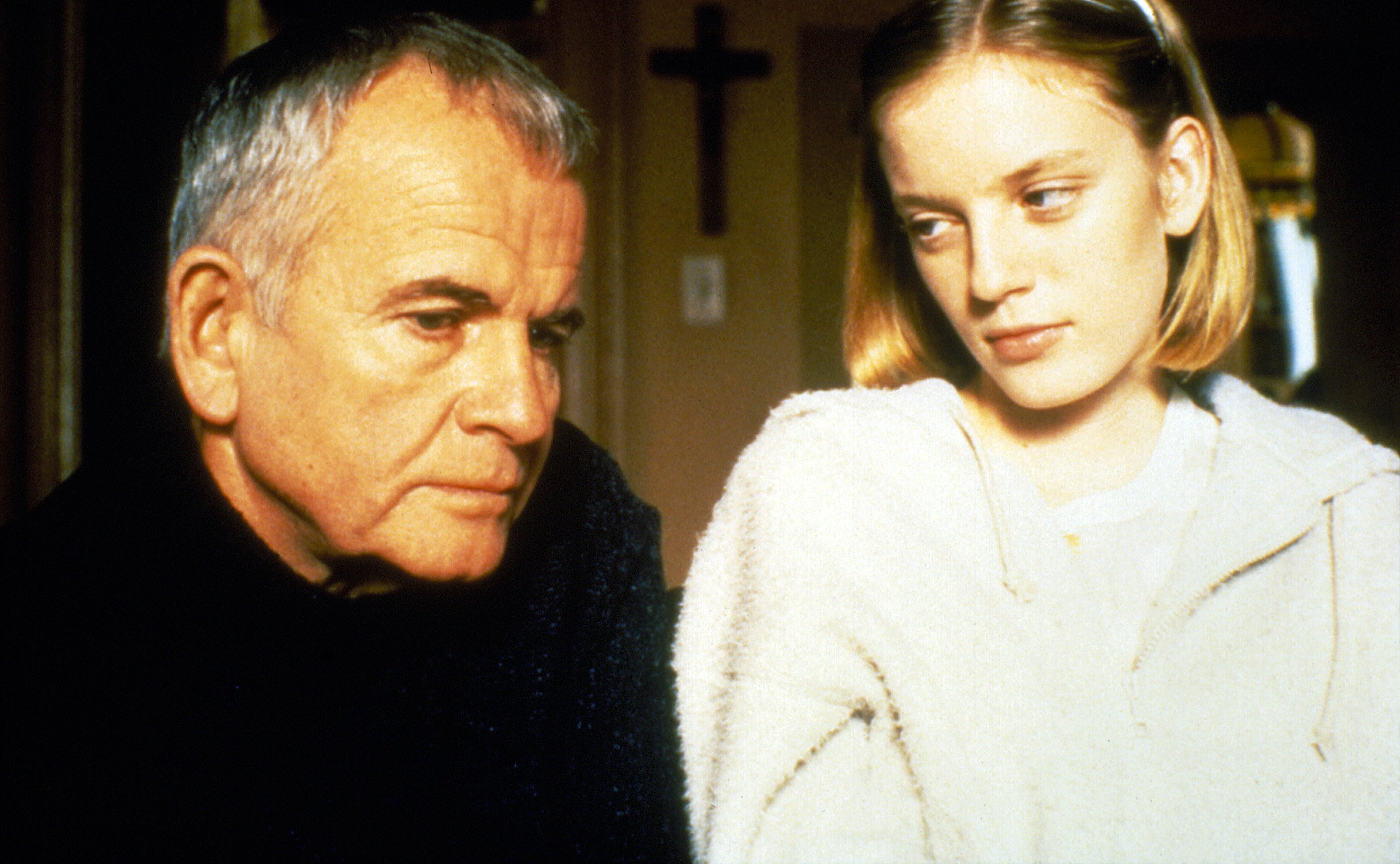

Second only to Cronenberg and deeply influenced by his example has been the Egyptian-born, BC-raised Atom Egoyan. He has also forged a singular path. His career has been built slowly but deliberately, from his first feature, the precocious Next of Kin (1984), through Family Viewing (1987), Speaking Parts (1989), The Adjuster (1991) and Exotica (1994) to the highly acclaimed, Oscar-nominated The Sweet Hereafter (1997).

Yet Egoyan’s worldview shares many of the same attributes as Cronenberg’s. Both are concerned with the transformative power of technology, perhaps a uniquely Canadian obsession largely influenced by Marshall McLuhan. Egoyan’s universe is one of uncertainty, where dysfunctional families and psychologically-damaged individuals struggle with their murky pasts. Felicia's Journey (1999), based on a novel of the same name by Irish author William Trevor, was the first of Egoyan's films to be set outside Canada and the first that was not independently produced. He followed that film with the ambitious Ararat (2002), a complex meditation on the 1915 Armenian genocide, and Where the Truth Lies (2005), his less-than-successful Hollywood-style murder mystery. Adoration (2009) and Remember (2015) marked a return to the kind of small-scale, interwoven character drama at which he excels. His high-profile Chloe (2010), an erotic thriller starring Julianne Moore, Liam Neeson and Amanda Seyfried, Devil’s Knot (2013), a true-crime drama starring Reese Witherspoon and Colin Firth, and The Captive (2016), a mystery-thriller with Ryan Reynolds and Scott Speedman, were less successful attempts at Hollywood genre filmmaking.

This article is one of four that surveys the history of the film industry in Canada. The entire series includes: Canadian Film History: 1896 to 1938; Canadian Film History: 1939 to 1973; Canadian Film History: 1974 to Present; Canadian Film History: Notable Films and Filmmakers 1980 to Present.

See also: Quebec Film History: 1896 to 1969; Quebec Film History: 1970 to 1989; Quebec Film History: 1990 to Present; 30 Key Events in Canadian Film History; Exhibit Eh: Canadian Film History in 10 Easy Steps; Documentary Film; Canadian Film Animation; Experimental Film; Film Distribution; Top 10 Canadian Films of All Time; English Canadian Films: Why No One Sees Them; National Film Board of Canada; Telefilm Canada; Canadian Feature Films; Film Education; Film Festivals; Film Censorship; Film Cooperatives; Cinémathèque Québécoise; The Craft of Motion Picture Making.

Share on Facebook

Share on Facebook Share on X

Share on X Share by Email

Share by Email Share on Google Classroom

Share on Google Classroom