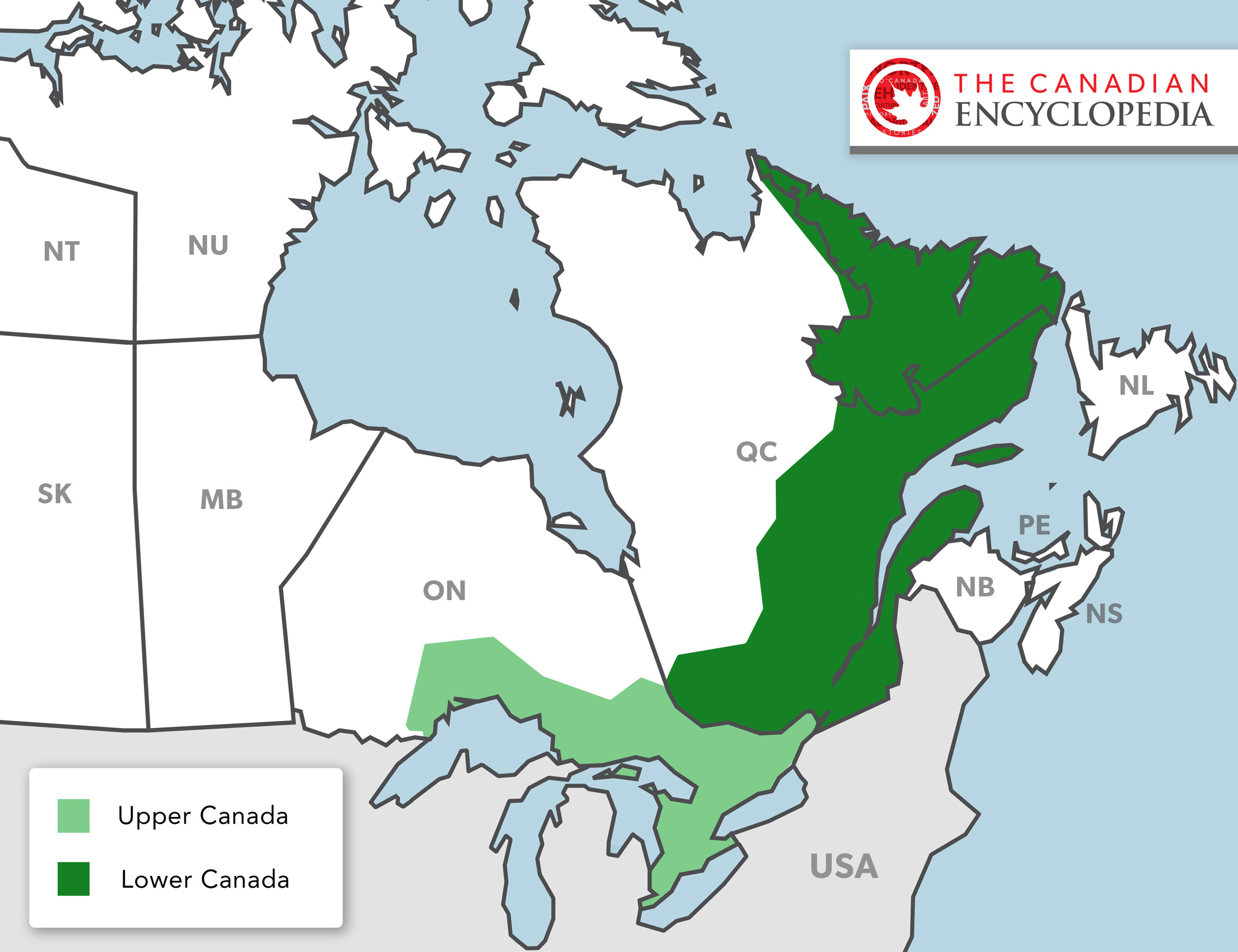

In late 1837, violent rebellions took place in Upper and Lower Canada. (See Rebellions of 1837–38 [Plain-Language Summary].) In May 1838, Lord Durham was sent from Britain to find out what had caused the unrest. His Report on the Affairs of British North America (1839) led to a series of reforms. These included merging the two Canadas into the Province of Canada. This was done through the Act of Union in 1841. The report also paved the way for responsible government. This was a vital step in Canada’s path toward democracy and independence from Britain.

This article is a plain-language summary of the Durham Report. If you would like to read about this topic in more depth, please see our full-length entry: Durham Report.

A Reformer’s Progressive Ideas

John George Lambton, the Earl of Durham, was a British reformer. His nickname was “Radical Jack.” He was made the governor general of British North America in 1838. He was asked to figure out what had caused the rebellions in Upper and Lower Canada in late 1837. He arrived in Canada in May 1838. He returned to Britain four months later. In 1839, he issued his Report on the Affairs of British North America.

The report was controversial. Its suggestions were advanced for their time. Durham proposed creating municipal governments and a supreme court in the BNA colonies. He also wanted to resolve the land question in Prince Edward Island. His long-held plan to unite all BNA colonies was dropped because Nova Scotia and New Brunswick were against it.

Durham’s report called for Upper and Lower Canada to be merged. It also called for responsible government in BNA. The British Parliament agreed to the first point. But it did not agree to the second.

Two Warring Nations

Durham felt that the problems in mostly French Lower Canada were ethnic, not political. He found “two nations warring in the bosom of a single state.” Durham was culturally biased against French Canadians. He called them “a people with no literature and no history.” He wanted to assimilate them by uniting the Canadas. He wanted to do this in a way that would give the mostly English Upper Canada more control. This would stop French Canadians from pursuing ethnic aims. It would also allow the mostly anglophone merchants in Lower Canada to pursue a strong St. Lawrence economy. This would ensure future prosperity.

Durham believed that capitalism would bring harmony and peace. But this would require reforms. He thought the constitutional system in Upper Canada was broken. Power was held tightly by the Family Compact. It was a group of ruling elites. It had been blocking economic and social development. Durham felt that this was a leading cause of the rebellion in Upper Canada.

Durham’s fix was to have a system in which colonial governments (in domestic matters, at least) had to answer to the electorate rather than the Crown. This would work if the executive (the Cabinet) was drawn from and had the support of the elected assembly. This would reduce the power of the Family Compact. It would stimulate colonial development. It would also strengthen ties with Britain and curb American influence.

Responsible Government

Durham’s Report was condemned by Upper Canada’s Tory elite. But Reformers there and in Nova Scotia hailed it. In Lower Canada, Montreal’s anglophone Tories were in favour of the union. They saw it as a way to overcome French Canadian opposition to their plans for economic development. French Canadians were opposed to the union. They wanted to defend their nationality.

In the end, the British government decided to unite the Canadas. (See Act of Union [Plain-Language Summary].) The Province of Canada came into being in 1841. It was governed by a joint legislature. The newly formed Canada West (Upper Canada) and Canada East (Lower Canada) had the same number of seats. But Canada West had a smaller population. So the French population in Canada East was under-represented. (See also Rep by Pop.)

The idea of responsible government was too much for the British government. They felt they needed tight control of the colonies to keep them loyal to Britain. It wasn’t until 1847 that the colonies were granted local self-government. (This was mainly so the government in London could reduce spending.) In 1848, the Reformers in Nova Scotia formed the first responsible government in the British Empire. In the Province of Canada, the Reformers were led by Robert Baldwin and Louis H. LaFontaine. Later in 1848, they formed a responsible government. It was also later granted in New Brunswick, PEI and Newfoundland.

Legacy

The Durham Report was controversial. It sought to assimilate French Canadians through a union of Upper and Lower Canada. French Canadians loathed Durham for this. But his report played a key role on Canada’s path toward democracy and independence from Britain.

See also Act of Union (Plain-Language Summary); Act of Union: Timeline; Act of Union: Editorial; Rebellions of 1837–38 (Plain-Language Summary); Responsible Government (Plain-Language Summary).

Share on Facebook

Share on Facebook Share on X

Share on X Share by Email

Share by Email Share on Google Classroom

Share on Google Classroom