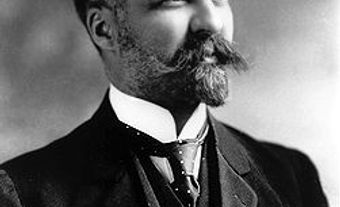

Robert-Errol Bouchette, MSRC, lawyer, journalist, Quebec civil servant and intellectual (born 2 June 1863 in Quebec City, QC; died 13 August 1912 in Ottawa, ON). He is best known for two works: a 1901 essay entitled Emparons-nous de l’industrie (Let’s Take Over the Industry), the title of which already foreshadows the topic, and a 1903 novel, Robert Lozé, which sets his ideas in fiction. Through his ideas, he sought to ensure the economic independence of French Canada.

Childhood and Early Career

Errol Bouchette was the grandson of geographer and surveyor general Joseph Bouchette, the son of Patriote and customs commissioner Robert-Shore-Milnes Bouchette, and a classmate of Léon Gérin, with whom he formed a close friendship at an early age. Errol attended the Petit Séminaire de Québec then enrolled in the Faculty of Law at Université Laval. Although he passed the bar exam in 1885, he did not immediately begin practicing law, but instead worked as a journalist from 1885 to 1893 (see Journalism). In 1898, he moved to Ottawa to work in the public service. He was initially employed as a clerk in the Public Works Department and then as a private secretary to the Minister of Inland Revenue. In 1903, he was appointed clerk to the Library of Parliament of Canada, a position he held until his death. He is best known for two works: a 1901 essay entitled Emparons-nous de l’industrie (Let’s Take Over the Industry), the title of which already foreshadows the topic, and a 1903 novel, Robert Lozé, which sets his ideas in fiction. Through his ideas, he sought to ensure the economic independence of French Canada.

A Passion for Political Economy

Errol Bouchette was active in a number of clubs and learned societies and joined the Institut canadien-français d’Ottawa in 1898 and the Royal Society of Canada in 1905. He made a name for himself with his passion for political economy. As head of the French section at the Library of Parliament, he had access to literature that was virtually unknown to the general public. In 1907, Fernand Rinfret, one of his journalist friends, wrote that “in an intimate conversation, bits of Karl Marx’s or Léon Say’s theories come to him at any moment, and he speaks of economists as though they were his best friends.” Under the influence of Léon Gérin, he also became a devoted supporter of the social science of French sociologist Frédéric Le Play, as disseminated by two of his pupils, priest Henri de Tourville and educator Edmond Demolins.

At a time when the decline of the French-Canadian nation was leading to a mass exodus to the United States, Bouchette was convinced that the solution to the crisis would be found in a rigorous study of the new conditions created by the development of Western civilization (see Franco-Americans). Therefore, he invited his compatriots to conduct empirical studies. Setting an example himself, he devoted a monograph inspired by Le Play (a social science method based on family observation) to the Scots of Cape Breton, in which he studied the social composition of the island’s population; another monograph followed on the francophones of Ontario. At the time of his death, he was working on a large-scale sociographic analysis of the inhabitants of the Chaudière Valley, in Beauce County, which he hoped to explore in the company of Léon Gérin.

According to Bouchette, through the direct and concrete study of social issues, social science will render irreplaceable the services of the French-Canadian community: it will be able to identify problems and suggest solutions for the national community (See also French Canadian Nationalism.)

“And this is where the usefulness of social science comes in. By pointing out the real causes of the inferiority of certain groups of men, it indicates at the same time how they can be combated and eliminated.” (Errol Bouchette, L’Évolution économique dans la Province de Québec (1901))

With agricultural production booming in the United States, and a multitude of factories, banks and businesses springing up there, social science could shed light on the challenges those subjected to this increasingly ruthless competition were facing. After all, Bouchette’s L’Indépendance économique du Canada français (1906), opens with a chapter entitled “Le Canada parmi les peuples américains” (Canada Among the American People).

Launching Reforms

According to Errol Bouchette, there is a law of humanity from which no one can escape: the more civilized people are destined to replace the so-called backward people. For him, advanced people are strong in their entrepreneurial spirit, their ability to innovate and their pursuit of material wealth; backward people neglect industrial activities and cling to dated traditions. “A people’s greatest weapon, the fundamental condition of their existence and progress, is economic superiority.” Therefore, to ensure the survival of the French-Canadian nation, Bouchette argued that French Canadians must “seize industry.”

For this program to have any chance of success, Bouchette recommended a series of reforms. He advocated for moderate intervention by the government, which was asked to encourage more rational planning of agriculture and industry. A system of loans to industrial and commercial enterprises, as well as subsidies and tax exemption policies, were to be organized to encourage French Canadians to exploit the country’s natural resources.

Bouchette also emphasized the role that education must play in national recovery because schools help shape strong, ambitious minds. By receiving an education better adapted to their times, children from “inferior” nations would be transformed until they could compete with children from the most modern nations. But the family had to take responsibility for the new education of which Bouchette dreamed. The social reform brought about by school, Bouchette believed, was only likely to achieve convincing results if it could count on young people who had already learned, at a very early age, the “lesson of race,” a lesson that “systematically exalted effort, but concentrated effort, impassive and without external demonstration, which increases a man’s strength tenfold in the face of an unwary enemy.”

Remembrance of Bouchette

Bouchette died of typhoid fever in August 1912. Although admired by his peers, his ideas had little influence. During his lifetime, his calls for a more economic vision of the future of the French-Canadian people disturbed elites who were more inclined to encourage “things of the mind.” Today, on the contrary, his ideas seem too timid to be claimed by anyone. This explains why the work of Bouchette has mostly been forgotten.

Awards and Distinctions

- Member of the Royal Society of Canada (1905)

Share on Facebook

Share on Facebook Share on X

Share on X Share by Email

Share by Email Share on Google Classroom

Share on Google Classroom