Income Distribution

Income Distribution refers to the share of total income in society that goes to each fifth of the population, or, more generally, to the distribution of income among Canadian households. Annual income is usually chosen as the indicator of a household's ability to meet its needs, primarily because the necessary statistical data are easily accessible. Economic well-being, however, also depends on other important factors.

Determining Factors of Income Distribution

In a capitalist economy such as Canada's, people derive their income from wages if they are employed, from INTEREST if they own financial capital, from profits (or dividends) if they are entrepreneurs and from rent if they own property. The earnings of production factors determine what is known as the distribution of "primary" income; wages and salaries alone account for roughly 85% of this income (see also CAPITAL FORMATION).

The interaction between supply and demand in each market determines the income of individuals and ultimately the distribution of primary income. For example, a hockey player's salary depends upon the supply and demand in the market for hockey players' services. Because a number of variables influence the supply of and demand for factors of production, the income generated is not the same for everyone, with the result that everyone does not receive the same share of primary income.

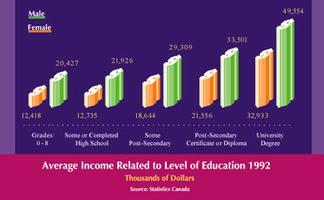

The following variables influence this distribution: skills, education, professional training and experience, working hours, compensatory salary differences, institutional restrictions, discrimination, differences in property wealth (including inherited wealth), opportunity, age and health. Primary income distribution is also modified by government intervention. The government influences income distribution in various ways, eg, through TAXATION, TRANSFER PAYMENTS and the provision of social goods and services.

Income Distribution in Canada

Statistics Canada annually conducts a survey of approximately 35 000 households, including families and single persons. According to Statistics Canada's classification, an "economic family unit" is a group of persons who share a common dwelling unit and who are related by blood, marriage or adoption. An "unattached individual" is a person living alone or in a household with others to whom he or she is not related.Total income includes wages and salaries, net income from self-employment, investment income (interest, dividends, rental income), retirement pensions, miscellaneous income such as scholarships and alimony, as well as government transfer payments (welfare, old-age security, family allowance, unemployment insurance, etc). This concept of total income, therefore, corresponds to primary income before taxes and after transfer payments.

Once information about income has been gathered, families are classified by increasing levels of income, from the poorest to the richest. They are divided into 5 groups, known as "quintiles," each representing 20% of all families. The first (or lowest) quintile comprises the poorest families and the last (or highest) quintile includes the richest. The income of the families of each quintile is then calculated in proportion to the income of all families. The percentage of income going to each group in society can thus be measured.

In 1985 families of the lowest quintile accounted for 6.3% of the total income, while those of the highest quintile earned 39.4%. Families of the first quintile had an annual income of less than $17 928 and those of the fifth quintile an income greater than $53 398 (see ELITES).

Other Statistics Canada figures reveal that families of the lowest quintile depend on govern- ment transfer payments for nearly 60% of their income. This group is composed mainly of welfare recipients and the elderly (who receive the old-age security pension and guaranteed income supplements), as well as single-parent families. However, wages and salaries account for nearly 80% of the income of families in the highest quintile, where there are often 2 breadwinners.

Income distribution, as measured by Statistics Canada, has been very stable over the past 30 years; ie, the share of income going to each quintile has varied only slightly. Such stability in income distribution is surprising because, during the same period, Canada experienced considerable economic growth and the average family income, corrected for INFLATION, nearly tripled. Moreover the WELFARE STATE, which came into existence during this time, created a considerable increase in government transfer payments.

Two factors are generally used to explain this stability. First, the differences in primary income have become more pronounced because of changes in lifestyle. Young adults and the elderly tend to live as independent households more often than they did a few decades ago, and the rise in the divorce rate has resulted in more single-parent families. Because these households generally have low incomes, the inequality of primary income has increased. Second, government transfer payments, a portion of which are earmarked for poorer people, narrow the disparities among total income.

Government intervention is not limited to transfer payments. The government also taxes income and provides social goods and services. The net redistributive impact of taxation and government expenditures is difficult to determine, but a number of hypotheses concerning those who carry the burden of taxation and those who benefit from government expenditures have been developed.

Some observers claim that, using 1969 data, there is a slight shift in income distribution from the richest families to the poorest. The richest families, representing roughly 25% of family units, provided a net contribution of 6.2% of total income. The effect of government redistribution is certainly smaller than might be expected, however, because only some government programs are designed specifically for the poorest people; most consist of transfers within the middle class itself.

A number of adjustments are required to define the "real" distribution of income in Canada. First, Statistics Canada's concept of income underestimates income derived from transfer payments, particularly from welfare. Some income, such as income in kind (eg, accommodation in low-rental housing), capital gains and transfers between persons is not included. Household production as well as income obtained from the UNDERGROUND ECONOMY are also omitted.

In addition, because income varies with age, consideration should be given to income obtained throughout a person's life. Lastly, the size of the family should also be taken into consideration. These adjustments are difficult to make and, as a result, the "real" distribution of income in Canada remains unknown.

Poverty

POVERTY, a complex social phenomenon, is not caused simply by inadequate income, although this is certainly a major factor. The poor in Canada are defined as those whose standard of living is below a certain level (usually called the "poverty line") and those who have serious difficulties participating actively in the life of society. Defined in this way, poverty is a relative phenomenon that can be measured by income levels.

Statistics Canada establishes the poverty thresholds (more precisely known as "low-income cutoffs") most commonly used in Canada. The thresholds are derived from a family expenditure survey conducted in 1978, which revealed that the average Canadian family spent 38.5% of its income on the basic needs of food, clothing and shelter. Statistics Canada then adds 20% to this share and considers that a family that must spend more than 58.5% of its income on basic needs is low income. It then defines low-income thresholds and indexes them annually to reflect increases in the CONSUMER PRICE INDEX. For example, the low-income thresholds of Canadian families living in large urban areas in 1985 were $10 233 for single persons and $20 812 for families of 4 persons.

In 1985, 13.1% of Canadian families and 36.6% of unattached individuals (representing 15.9% of the population or 3.9 million persons), were numbered as poor. Poverty is more common in the Atlantic provinces and Québec (see REGIONAL ECONOMICS), among young people and the elderly and in families (usually single-parent families) in which a woman is the head of the household.

In deciding whether Canada's income distribution in 1985 was slightly or very unequal, it is necessary to apply an ethical standard. If the standard adopted is that of "equal sharing" of income, which would result in equal distribution, it is possible to measure and visualize the inequality using a Lorenz curve. The vertical axis reveals the cumulative proportion of the total income, and the horizontal axis reveals the cumulative proportion of the population. If each family earns an identical income, 20% of families will enjoy 20% of the income, 40% of the families 40% of the income and so on. Income distribution will therefore be represented by the straight line of complete equality. The curve located under the straight line represents income distribution in Canada in 1985. The farther the curve is from the straight line, the more unequal the distribution.

Canadian society is ambivalent in its support of the standard of "equal sharing," although numerous government income-security programs do attempt to compensate somewhat for the disparity in results. Moreover, the principle of "equal opportunity" probably corresponds, at least partly, to the moral philosophy of Canadian society.

A number of government policies focusing on education for young people, for example, are based on the principle of equal opportunity. But even if absolutely equal opportunity were achieved for children, certain income disparities would persist in their adult life because of wealth and other advantages, and because of different attitudes towards education, work and savings.

Guaranteed Annual Income

Since the early 1960s, a universal solution to poverty and income disparities has been proposed regularly in North America: guaranteed annual (or minimum) income (known as "negative income tax" when incorporated into the tax system).

This income has 2 components. First, a guaranteed annual income level is determined, below which no family's income is allowed to fall. This income level is based on the needs of each family (by size) and could be the same as the poverty threshold. Theoretically such an income is now provided through welfare payments. Second, while welfare payments are now taxed at $1 for each $1 earned over and above the welfare payments, a guaranteed annual income would be reduced at a lower tax rate (eg, 50c for each $1 of earnings).

Many people share the view that income disparities could be narrowed considerably if the government had the political will to tax the rich more heavily and redistribute wealth to the poor (see TAXATION, ROYAL COMMISSION ON). However, any significant redistribution would imply a major rise in taxation for families with an income over $40 000, and it is highly unlikely that these families, considered middle class, would want to accept such a tax hike.

Share on Facebook

Share on Facebook Share on X

Share on X Share by Email

Share by Email Share on Google Classroom

Share on Google Classroom