Irene Ayako Uchida, OC, geneticist (born 8 April 1917 in Vancouver, BC; died 30 July 2013 in Toronto, ON). Dr. Uchida pioneered the field of cytogenetics in Canada, enabling early screening for chromosomal abnormalities (i.e., changes in chromosomes caused by genetic mutations). She discovered that women who receive X-rays during pregnancy have a higher chance of giving birth to a baby with Down syndrome and other chromosomal abnormalities. She also discovered that the extra chromosome that causes Down syndrome may come from either parent, not only the mother.

Click here for definitions of key terms used in this article.

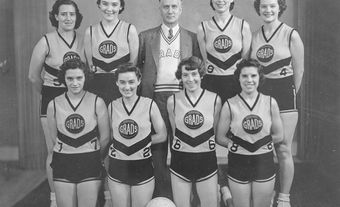

Geneticist Irene Ayako Uchida made strides in the study of genetic conditions such as Down syndrome.

Early Life and Education

Irene Uchida was born Ayako Uchida to first-generation Japanese immigrants Sentaro and Shizuko Uchida. The family lived in the working-class Vancouver neighbourhood now known as Hastings-Sunrise. In her early years, Uchida enjoyed playing piano, organ and violin. She often performed for her church, the Japanese United Church. Her music teacher, claiming to have trouble pronouncing her given name, began calling her Irene. Uchida liked the name and adopted it as her own.

Following the death of her best friend in a car crash and that of her sister Sachi to tuberculosis, Uchida became determined to help people throughout her life.

She enrolled in English at the University of British Columbia (UBC) after high school. During this period, she also worked to advance the rights of Japanese Canadians. To this end, Uchida joined the Japanese Canadian Citizens League and wrote for the community’s The New Canadian newspaper. She took a break from her studies and travelled to Japan after two years at UBC.

Did you know?

Irene Uchida’s aunt, Chitose (Josi) Uchida, was the first Japanese Canadian to enroll at UBC and became its first female graduate in 1916.

Wartime Experience

In November 1941, Irene Uchida returned home on the last ship from Yokohama, Japan, to Canada during the Second World War. Soon thereafter, she and her family were among the 22,000 Japanese Canadians whom the federal government forcibly moved to internment camps. The family was first sent to Christina Lake in British Columbia’s Kootenay region. In 1942, Uchida and her father were moved to Lemon Creek. Her friend from Vancouver, Hide Hyodo, convinced her to open a school for interned children. She took on the roles of principal and teacher at the Lemon Creek camp until 1944. (See also Japanese Canadian Internment: Prisoners in Their Own Country.)

BA and PhD Degrees

After the war, Irene Uchida remained in Canada despite persistent anti-Japanese racism and the return of most of her family to Japan. She continued her education at the University of Toronto with funding and lodging from the United Church of Canada. Uchida graduated with a BA in English literature in 1946. During this period of her life, she also worked as a seamstress to help put herself through school.

Uchida planned to pursue a master’s degree in social work after her BA. However, this changed after Dr. Norma Ford Walker, who had taught her an introductory genetics course, encouraged her to continue in genetics. She pursued a PhD in zoology, which she earned in 1951.

Meet Irene Uchida. A Japanese Canadian scientist, she was one of thousands of Japanese Canadians who were imprisoned as part of the Japanese Internment during WWII. Dr. Uchida went on to become a groundbreaking geneticist, transforming maternal and fetal health around the world.

Note: The Secret Life of Canada is hosted and written by Falen Johnson and Leah Simone Bowen and is a CBC original podcast independent of The Canadian Encyclopedia.

Career Highlights

From 1951 to 1959, as a research associate at Toronto’s Hospital for Sick Children, Irene Uchida developed one of the largest twin registries (databases) in North America. She used it to research the genetic disorders of twins with heart disease.

Encouraged by Dr. Bruce Chown, a prominent pediatrician, Uchida pursued her long-term goal of developing a genetics lab in Winnipeg, Manitoba. In 1959, with Chown’s help, she obtained a one-year Rockefeller Foundation grant to study at the University of Wisconsin. At first, the United States refused her entry. Border officials regarded her as Japanese despite her birth in Canada. Their entry quota for Japanese had been filled for the year. Eventually, with help from the university’s president, she obtained a special pass. Her work in Wisconsin focused on chromosomes in fruit flies.

In 1960, the Children’s Hospital in Winnipeg hired her as its director of medical genetics. There, Uchida developed a clinical test for trisomy-18 (Edwards syndrome), thereby founding Canada’s first cytogenetics program.

Science is a rewarding and challenging career. Young people going into science must keep an open mind to all ideas in an effort to find every possible way to help people.

— Irene Uchida

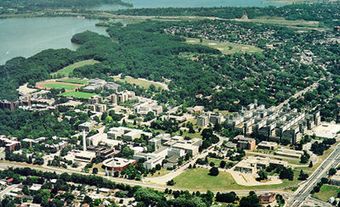

In 1969, Uchida was a visiting scientist at the University of London and at an atomic energy laboratory in Harwell, UK. She learned techniques to study the effects of radiation on mouse eggs and sperm during this year abroad. Following her return, she moved to McMaster University in Hamilton, Ontario. She founded McMaster’s cytogenetics laboratory and became a professor in its pediatrics and pathology departments until 1991. From 1991 to 1995, she directed the cytogenetics lab at Oshawa General Hospital.

Over the course of her career, Uchida published nearly 100 medical papers.

An example of the fluorescence microscopy technology that Dr. Uchida used to study chromosomal defects during her time at McMaster University.

Key Discoveries

In 1960,Irene Uchida developed Canada’s first diagnostic blood test to karyotype the chromosomes of infants. Two years later, she published detailed case studies of trisomy-18 (Edwards syndrome) in humans. Clinicians later used her method to detect chromosomal abnormalities in a fetus by testing the amniotic fluid that surrounds the fetus in the womb.

Uchida studied the relationship between pregnancy, X-rays and chromosomal abnormalities. Through investigative interviews of parents, she demonstrated the prevalence of Down syndrome in people who had been exposed to X-rays before birth.

Uchida later showed that the trisomy that causes Down syndrome can come from either parent. It was previously thought that only the mother could pass it on to her child.

Uchida was also a pioneer in the use of fluorescent chromosome banding to study abnormalities in developmental genes.

Death and Legacy

Irene Ayako Uchida died 30 July 2013 after a long battle with Alzheimer’s disease.

As an early member of the Canadian College of Medical Geneticists, Uchida helped shape the training of many Canadian laboratory and medical geneticists. She also left a legacy in pediatrics. Every two years since 1997, the University of Manitoba has held the Irene Uchida Lecture. The talk is part of the university’s Pediatric Grand Rounds, a series of weekly presentations for pediatricians.

Ingenium (Canada’s Museums of Science and Innovation) featured Uchida as part of its travelling exhibit Iron Willed: Women in STEM. The exhibit began a three-year tour in 2019. Ingenium cited Uchida as “the first Canadian and the first woman to study the effects of radiation on unborn babies.”

Share on Facebook

Share on Facebook Share on X

Share on X Share by Email

Share by Email Share on Google Classroom

Share on Google Classroom