Ukrainian Canadians are Canada's eleventh largest ethnic group; Canada has the world's third-largest Ukrainian population behind Ukraine itself and Russia. Slightly more than 110,000 Ukrainian Canadians reported Ukrainian as their mother tongue, and more than half live in the Prairie Provinces.

Ukrainian immigrants and their descendants have left a profound mark on the development of Ontario and Western Canada. They have made and continue to make remarkable contributions to Canada in the fields of culture, the economy, politics and sports. Distinguished Canadians of Ukrainian ethnic origin include Stephen Worobetz, Michael Luchkovich, Sylvia Fedoruk, Peter Liba, Ramon Hnatyshyn, Paul Yuzyk, Roy Romanow, Gary Filmon, Ernest Eves, Mary Batten, Filip Konowal, Jaroslav Rudnyckyj, William Kurelek, Luba Kowalchyk, Luba Goy, George Ryga and Roberta Bondar, the first Canadian woman to walk in space, as well as many players in the National Hockey League, such as Johnny Bucyk, Wayne Gretzky, Dale Hawerchuk and Mike Bossy.

Overview

In the 19th century, the Russian Empire ruled 80 per cent of Ukraine; the rest lay in the Austro-Hungarian provinces of Galicia, Bukovina and Transcarpathia. As serfs in Austria-Hungary until 1848 and in the Russian Empire until 1861, Ukrainians suffered from economic and national oppression. When attempts to establish an independent Ukrainian state from 1917 to 1921 collapsed, the greater portion of Ukraine became a republic in the USSR, while Poland, Romania and Czechoslovakia divided the remainder. Following the Second World War the western Ukrainian territories were annexed by the Ukrainian Soviet Socialist Republic.

In 1991, with the collapse of the Soviet Union, Ukraine became an independent state. Canada was the first western country to recognize Ukraine and has maintained strong ?bilateral ties with it ever since. During Ukraine’s Orange Revolution in 2004, Canada sent a group of election observers into the field. On several occasions since the Russian incursion in 2014, Canada has demanded that Russia withdraw its soldiers from Ukrainian territory. The Ukrainians constitute, after the Russians, the largest Slavic nation in Europe.

Immigration History and Settlement

Isolated individuals of Ukrainian background may have come to Canada during the War of 1812 as mercenaries in the de Meurons and de Watteville Swiss regiments. It is possible that others participated in Russian exploration and colonization on the West Coast, came with Mennonite and other German immigrants in the 1870s, or entered Canada from the US.

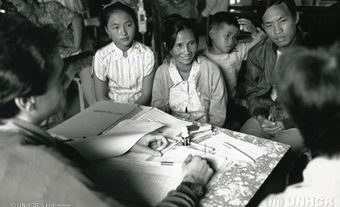

The first major immigration (170,000 rural poor, primarily from Galicia and Bukovina) occurred between 1891 and 1914. Ivan Pylypow and Wasyl Eleniak, who arrived in 1891, are generally considered the first two Ukrainian immigrants to Canada. Immigration grew substantially after 1896 as Canada promoted the immigration of farmers from Eastern Europe.

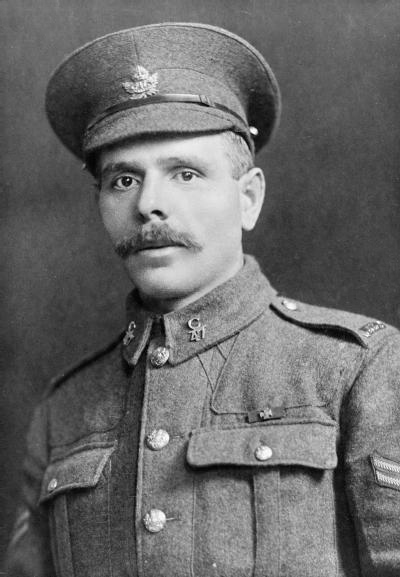

With the outbreak of the First World War, immigration virtually ceased and unnaturalized Ukrainians were classified as "enemy aliens" by the Canadian government. At the same time, over 10,000 Ukrainians enlisted in the Canadian Armed Forces. (See Filip Konowal.) Between both world wars some 70,000 Ukrainians immigrated to Canada for political and economic reasons. They included war veterans, intellectuals and professionals, as well as rural farmers. Between 1947 and 1954, some 34,000 Ukrainians, displaced by the Second World War, arrived in Canada. Representing all Ukrainian territories, they were the most complex socioeconomic group.

While the Prairie Provinces absorbed the bulk of the first two immigration cohorts, displaced persons settled mainly in Ontario. From the mid-1950s through the 1960s, only a few Ukrainians entered the country annually. In the 1970s and 1980s, however, limited renewed immigration from Poland and the Soviet Union saw perhaps 10,000 ethnic Ukrainians and Soviet Ukrainian Jews come to Canada. Since 1991, a modest but growing number of immigrants have come to Canada from Ukraine, largely because of the country’s political and economic instability. From 2001 to 2016, Canada welcomed 40,015 new permanent residents from Ukraine.

Commemoration of First World War Concentration Camps

During the First World War, approximately 80,000 Ukrainian Canadians were forced to register as "enemy aliens," report to the police on a regular basis, and carry government-issued identity papers at all times. Those naturalized for less than 15 years were disenfranchised. Another 5,000 Ukrainians, mostly men, were placed in concentration camps where they endured hunger and forced labour, helping to build some of Canada's best known landmarks such as Banff National Park. Some died and many fell sick or incurred injuries.

For many years, Canada’s internment of Ukrainians (along with Germans, Romanians, Slovaks, Czechs, Hungarians and Poles) was a taboo subject rarely addressed in history books. But in 2005, Parliament acknowledged its responsibility for these events by passing the Internment of Persons of Ukrainian Origin Recognition Act. The Act also provides for recognition of these events through “public education and the promotion of the shared values of multiculturalism, inclusion and mutual respect.” In 2008, in keeping with this legislation, the Government of Canada and a number of Ukrainian Canadian associations established a $10 million endowment known as the Canadian First World War Internment Recognition Fund to finance projects for the purpose of educating Canadians about this subject.

In June 2013, Parks Canada opened a permanent exhibit in Banff National Park about the history of internment in Canada during the First World War. The title of this 305 m2 exhibit is Enemy Aliens, Prisoners of War: Canada's First World War Internment Operations, 1914-1920, and its purpose is to increase public awareness about Canada’s internment of 8,579 enemy aliens as prisoners of war at locations throughout the country. However, critics argued that the exhibit did not go far enough in addressing Canadian government culpability. On 22 August 2014, on the 100th anniversary of Parliament’s adoption of the War Measures Act, the Ukrainian Canadian Civil Liberties Association, together with the Government of Canada, unveiled 100 plaques across the country to commemorate the internment of several thousand people during the First World War.

Urban and Rural Patterns of Settlement

By 1914, the Prairie Provinces were marked by several rural Ukrainian block settlements, extending from the original Edna (now Star) colony in Alberta through the Rosthern and Yorkton districts of Saskatchewan to the Dauphin, Interlake and Stuartburn regions of Manitoba. While most Ukrainians chose to homestead, some became wage workers in resource industries in such places as the Crowsnest Pass, Alberta, Cape Breton Island, Nova Scotia and Northern Ontario.

During the 20th century, immigrants and migrants from the rural blocks also began to develop Ukrainian urban communities in various Canadian towns and cities. Today, Edmonton has by far the largest such community. In 2016, 12 to 16 per cent of the residents of Edmonton, Winnipeg and Saskatoon had Ukrainian heritage, compared with only 2.5 per cent in Toronto, which nevertheless has a Ukrainian Canadian population of more than 144,000. Also in 2016, 51 per cent of Ukrainian Canadians resided in the Prairie Provinces, 27.7 per cent lived in Ontario and 16.8 per cent in British Columbia and only 3 per cent in Québec. Of the 1,359,655 Canadians who reported Ukrainian origins, 273,810 reported Ukrainian as their only ethnic origin and another 1,085,845 reported partial Ukrainian ancestry.

Economic Life

Ukrainians homesteaded initially with limited capital, outdated technology and no experience with large-scale agriculture. High wheat prices during the ?First World War led to expansion based on wheat, but during the 1930s, mixed farming prevailed. Since the ?Second World War mechanization, scientific agriculture and out-migration (movement to a different part of a country or territory) in the Ukrainian blocks have paralleled developments elsewhere in rural western Canada. Ukrainian male wage earners found jobs as city labourers, miners, and railway and forestry workers; their female counterparts became domestic servants, waitresses and hotel help (see ?Domestic Service in Canada). Discrimination and exploitation radicalized many Ukrainian labourers. As a group, Ukrainians benefited from occupational diversification and specialization only after the 1920s; teaching was the first profession to attract significant numbers of both men and women.

By 1971, the proportion of Ukrainian Canadians in agriculture had decreased to 11.2 per cent, slightly above the Canadian average, and workers to 3.5 per cent of the Ukrainian male labour force. In 1991, Ukrainians remained overrepresented in agriculture compared to Canadians as a whole, but they were well distributed across the economic spectrum, including the more prestigious and semi-professional and professional categories.

With Ukrainian integration into Canadian society, it has become increasingly difficult to determine if or how ethnicity affects the occupational and career patterns of younger Canadian-born generations.

Social Life and Community

The first Ukrainian block settlements and urban enclaves cushioned immigrant adjustment but could not prevent all problems of dislocation. Local cultural-educational associations, fashioned after Galician and Bukovinan models, maintained interest in the homeland and instructed the immigrants about Canada. The existing Ukrainian Canadian community assisted the adjustment of both interwar and postwar immigrants. It also extended material and moral aid to various humanitarian and political causes in Ukraine, including state-building efforts after independence.

National organizations emerged in the interwar years. The pro-communist Ukrainian Labour-Farmer Temple Association (ULFTA) established in 1924 attracted the unemployed in the 1930s. The Ukrainian Self-Reliance League (established in 1927) and the Ukrainian Catholic Brotherhood (established in 1932), together with their women's and youth affiliates, represented Orthodox and Catholic laity. Moreover, organizations introduced by the second wave of immigration reflected Ukrainian revolutionary trends in Europe. The small conservative, monarchical United Hetman Organization (established in 1934) was counterbalanced by the influential nationalistic republican Ukrainian National Federation of Canada (established in 1932).

Despite tensions, all non-communist groups publicized Polish pacification and Stalinist terror in Ukraine in the 1930s. The ULFTA criticized foreign rule in western Ukraine but condoned the Soviet purges and artificial famine of 1932–33, known today as the Holodomor, that killed several million people; its successor, the Association of United Ukrainian Canadians (established in 1946), has declined steadily, first with the Cold War and then the collapse of the Soviet Union. In 1940, to unite Ukrainian Canadians behind the Canadian war effort, non-communist organizations formed the Ukrainian Canadian Committee (known as the Canadian Ukrainian Congress since 1990). It became a permanent coordinating superstructure with such political objectives as the admission of Ukrainian refugees after 1945, support for multiculturalism and Canada-sponsored projects in independent Ukraine.

The major organizations introduced by the third wave of immigration were the intensely nationalistic Canadian League for the Liberation of Ukraine (established in 1949; now the League of Ukrainians Canadians), and Plast Canada, a scouting youth group (established in 1948). Both groups maintain ties with like-thinking Ukrainians around the world. In the 1970s, the Ukrainian Canadian Professional and Business Federation (established in 1965) was politically significant and was able to secure public benefits for the Ukrainian community.

The St. Petro Mohyla Institute, founded in 1916 and located near the ?University of Saskatchewan, hosts cultural activities for the Ukrainian Canadian community of Saskatoon and provides a residence for university students of Ukrainian ancestry. The institute also offers summer courses on Ukrainian language, literature, art and history. The Ukrainian Cultural Centre of Toronto, until it sold its building in 2013, hosted various cultural events for Toronto’s Ukrainian Canadian community and housed the offices of the Ukrainian Canadian national newspaper Homin Ukrainy (Ukrainian Echo) and the Ukrainian Youth Association of Canada. English-language courses and cultural activities for Ukrainian Canadians and Ukrainian newcomers in Toronto are now held at St. Volodymyr’s Ukrainian Orthodox Cathedral.

Ukrainian Canadians have published nearly 600 newspapers and periodicals, most of which espouse a particular religious or political philosophy (see Ukrainian Writing). Increasingly, Canadian-born generations no longer find the ethnic press relevant, but there is still a healthy interest in Ukrainian topics and affairs. Bilingual and English-language publications compensate for the decline in Ukrainian-language readers.

Religious Life

While Ukrainians from Galicia were Eastern-rite Catholic (see Catholicism), those from Bukovina were Orthodox (see Orthodox Church). No priests initially immigrated to Canada, and other denominations — especially the Methodist and Presbyterian churches — tried to fill the religious and social vacuum. Until 1912, when they acquired an independent hierarchy, Ukrainian Catholics were under Roman Catholic jurisdiction. The Russian Orthodox Church worked among Orthodox immigrants but rapidly lost popularity after 1917. In 1918, Ukrainians who were opposed to centralization and Latinization in the Ukrainian Catholic Church founded the Ukrainian Greek Orthodox Church (since 1989, the Ukrainian Orthodox Church) of Canada. Both churches became metropolitanates (or bishoprics): the Ukrainian Orthodox Church of Canada in 1951 followed by the Ukrainian Catholic Church in 1956.

Long central in preserving the language, culture and identity of Ukrainian Canadians, the two churches have seen their religious dominance, moral authority and social influence undermined by assimilation. According to the 1991 census, 23.2 per cent and 18.8 per cent of single-response Ukrainian Canadians belonged to the Ukrainian Catholic and Ukrainian Orthodox churches respectively; 20.1 per cent were Roman Catholic and 10.9 per cent United Church adherents; another 12.6 per cent reported no religion. According to the 2011 National Household Survey, 51,790 people in Canada belong to the Ukrainian Catholic Church and 23,845 to the Ukrainian Orthodox Church of Canada (respectively 4.1 per cent and 1.9 per cent of all Ukrainian Canadians). One reason for the apparent decline in religion among Ukrainian Canadians is that, like Canadians in general, more and more Ukrainian Canadians report that they do not belong to any religion (the figure for Canadians as a whole in 2011 was 23.9 per cent).

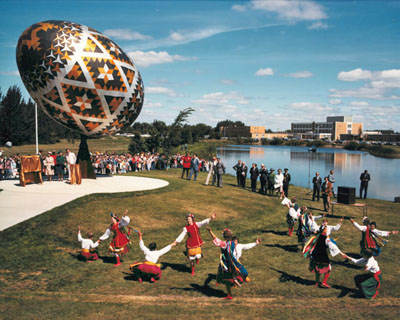

Most agricultural pagan-Christian rituals of Ukrainian rural life were discarded with urbanization and secularization. Embroidery, Easter egg ornamentation, dance, music and foods remain popular and have also won widespread appreciation outside the Ukrainian Canadian group. Ukrainian Canadians have also introduced a distinctive religious architecture that artfully combines Ukrainian traditions with contemporary North American motifs. It is characterized by exterior domes, interior wall murals and a partition (the iconostasis) separating the nave from the sanctuary.

Cultural Life

Many Ukrainian Canadian artists look to their heritage in both Canada and Ukraine for inspiration and subject matter. Community archives, museums and libraries — like the Ukrainian Cultural and Educational Centre in Winnipeg established in 1944 by the Ukrainian National Federation of Canada, and the Ukrainian Cultural Heritage Village located east of Edmonton — actively preserve the Ukrainian Canadian heritage. Certain art forms have remained static while others have evolved. Dance ensembles have experimented with Ukrainian Canadian themes (see Ukrainian Shumka Dancers) and Ukrainian Canadian country music has combined Ukrainian folk and western Canadian elements.

The paintings of William Kurelek, inspired by his Ukrainian prairie pioneer experience, have been widely recognized in Canada. In the musical field, the 1980s Juno-winning Luba Kowalchyk began her career in Ukrainian popular music (see Ukrainian Music in Canada). Numerous Ukrainian-language poets and prose writers have described Ukrainian life in Canada; George Ryga is one of a handful of English-language writers of Ukrainian origin to achieve national stature.

Since the 1970s, several films have recorded and critically interpreted the Ukrainian Canadian experience. Once-vibrant live theatre, particularly important to immigrant generations, has all but disappeared. Ukrainian Canadians publicly celebrate their heritage through a number of annual events — the best known is Canada's National Ukrainian Festival, held for the past 50 years in Dauphin, Manitoba.

Education

After 1897, Ukrainians in Manitoba took advantage of opportunities for bilingual instruction (in English and Ukrainian) under specially trained Ukrainian teachers. Bilingual schools operated unofficially in Saskatchewan until 1918 but they were not allowed in Alberta. Criticized for retarding assimilation of Ukrainian children, they were abolished in Manitoba in 1916 despite Ukrainian opposition.

Vernacular community-run schools expanded rapidly after the First World War to preserve the Ukrainian language and culture. They now reach only a fraction of youth; most schools exist in urban areas at the elementary level and are particularly popular in Toronto. Pioneer residential institutes provided Ukrainian surroundings for rural students pursuing their education and produced many community leaders.

Russification of Ukraine spurred Ukrainian Canadians to mobilize politically and seek public support for their language and culture. Between the 1950s and the 1980s, they obtained Ukrainian-content university courses and degree programs, recognition of Ukrainian as a language of study and subsequently of instruction in Prairie schools. The University of Alberta and the University of Toronto operate the Canadian Institute of Ukrainian Studies (established in 1976).

In 1981, the Centre for Ukrainian Canadian Studies was established by the University of Manitoba and St. Andrew’s College of Winnipeg. The Prairie Centre for the Study of Ukrainian Heritage, an academic unit of St. Thomas More College of the University of Saskatchewan, was created in 1999, with the mission of promoting the study of various aspects of Ukrainian heritage in Canada.

The 2016 Census recorded 110,580 people who reported Ukrainian as their mother tongue (first language learned). Illiteracy, common among the first wave of immigration, has virtually disappeared. Any persisting educational disparities between Ukrainians and their fellow citizens are largely linked to age and immigration. Otherwise, Ukrainian educational levels generally reflect Canadian norms.

Political Life and Legacy

At the polls, Ukrainians initially tended to vote Liberal, but their low socioeconomic status also drew them to protest parties — later, many approved the anti-communism of the Diefenbaker Conservatives. Increasingly, Ukrainians' voting patterns reflect those of their economic class or region.

Ukrainians originally entered Canadian politics at the municipal level, and in rural areas where they were numerically dominant they came to control elected and administrative organs. William Hawrelak in Edmonton and Stephen Juba in Winnipeg were prominent mayors. The first Ukrainian elected to a provincial legislature was Andrew Shandro, a Liberal, in Alberta in 1913. In 1926, Michael Luchkovich of the United Farmers of Alberta became the first Ukrainian in the ?House of Commons.

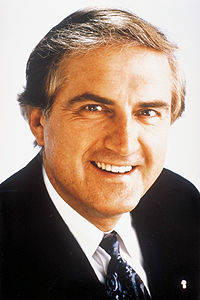

Since then, many Ukrainian candidates have been successful provincially and federally, and Ukrainians have been appointed to federal and provincial Cabinets. There have been many senators of Ukrainian origin and three Ukrainian Canadians have received vice-regal appointments. Stephen Worobetz was lieutenant-governor of Saskatchewan (1970–76) as was Sylvia Fedoruk (1988–93). From 1999 to 2004, Peter Liba was lieutenant-governor of Manitoba. In 1990, Ramon Hnatyshyn became the second governor general of non-British and non-French origin. Other notable figures of Ukrainian origin have included Roy Romanow, premier of Saskatchewan (1991-2001), Gary Filmon, premier of Manitoba (1988-99), Ernest Eves, premier of Ontario (2002-03), ?Ed Stelmach, premier of Alberta (2006-11), Mary John Batten, the first woman to sit as a District Court judge in Saskatchewan and the second woman to sit on the ?Federal Court of Canada, and Chrystia Freeland, Canada's Minister of Foreign Affairs (from 2017 to 2019) and Minister of Finance (since 2020.

Many intellectuals from the Ukrainian Canadian community, such as historian and senator Paul Yuzyk and linguist Joroslav Rudnyckyj, have played a prominent role in defining Canadian multiculturalism. In 2009, the Government of Canada established the Paul Yuzyk Award for Multiculturalism, which was given each year to individuals, groups and organizations that made exceptional contributions to multiculturalism and the integration of newcomers. In 2018, the award was renamed the Paul Yuzyk Youth Initiative for Multiculturalism and repurposed by the Department of Canadian Heritage as a grant to support youth engagement initiatives.

Share on Facebook

Share on Facebook Share on X

Share on X Share by Email

Share by Email Share on Google Classroom

Share on Google Classroom