Family Background

Susan Agnes Bernard was the youngest of five children (and only surviving daughter) born to Theodora and Thomas Bernard. The Bernards were plantation owners and held a number of key positions in the military and government in Jamaica. When Thomas died during a cholera epidemic in 1850, the two eldest Bernard sons, Hewitt and Richard, established a new home for the family in what is now Barrie, Ontario. The Bernard and Macdonald families first met after Hewitt become private secretary to John A. Macdonald, then attorney general of Canada West. It is believed that Hewitt discouraged any initial romantic interest between John A. and Agnes because he was aware of his employer’s heavy drinking and feared for his sister’s happiness.

In any event, political events complicated such personal matters when Ottawa was made capital of the Province of Canada in 1865. The young city was known as a rustic and rowdy place, and Agnes and Theodora may have received similar advice as Frances Monck (sister-in-law of Governor General Monck), who was warned to “Keep out of it [Ottawa]… as long as you can.” Therefore, while Hewitt made plans to join the government in Ottawa, the two women chose instead to join family and friends in England.

One year later, political events prompted a different outcome for Agnes and John A. After a chance encounter in England during the London Conference, the couple courted, wed and enjoyed a short honeymoon in Oxford — all while attending the meetings and social events that accompanied Confederation proceedings. Pleased by the personal and political success of his time in London, the witty John A. was said to have “alluded to the plan of confederation, whereby all the provinces of Canada were united under one female sovereign, and that perfection of the idea of union had so occupied his mind that he had sought to apply it to himself.”

Through marriage, Agnes gained a stepson, Hugh John, and she and Sir John A. had a daughter together. Mary Theodora was born in February 1869, and suffered from a hydrocephalic condition, which meant that she required extensive care and was never able to live independently. However, Mary was a much-loved child who lived a full life. When she died at the age of 64, she had outlived both of her parents, as well as her stepbrother.

Prime Minister’s Wife

As part of the official ceremonies that marked Canada’s first Dominion Day, John A. Macdonald received the title of Knight Commander of the Bath. As such, Agnes Macdonald enjoyed a similar change in social status and address, and the couple was thereafter known as Sir John A. Macdonald and Lady Agnes Macdonald.

Lady Macdonald held the position of prime minister’s wife twice: from 1867 to 1873, and from 1878 to 1891. This second period ended when Sir John A. died in June 1891. As prime minister’s wife, Lady Macdonald set the standard for the 19th-century ideal of womanly behaviour — one that was devoutly religious, dedicated to family and committed to various good works in the community. This devotion translated into regular attendance at St. Alban’s Anglican Church, constant concern for the health of her husband and mother and the position she held as First Directress of the Ottawa Orphans’ Home. We encounter this womanly ideal throughout Lady Macdonald’s diary, where she reveals her desire to “walk more closely with Him — be more entirely His — spend & be spent in his service — die to Him & live unto righteousness” (12 January 1868).

Lady Macdonald was also expected to support her husband’s political career by hosting social events and dinner parties for his colleagues, and adopting his “pursuits & occupations” (Lady Macdonald, 7 July 1867). Evidence suggests that she did not find social events easy or enjoyable, but was far more comfortable in the Ladies’ Gallery in the House of Commons. There she was known for transmitting messages to her husband using sign language for the deaf, or railing against his political opponents. Following a particularly heated debate during the 1878 session, Prime Minister Alexander Mackenzie observed a rather unseemly outburst when “Lady Macdonald in the gallery, like the Queen of the day, stamped her foot and exclaimed ‘Did ever any person see such tactics!!’”

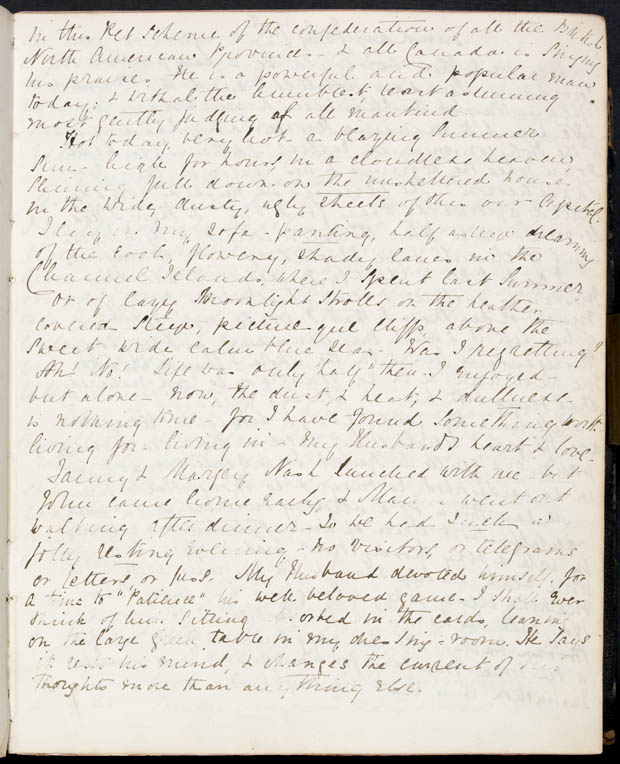

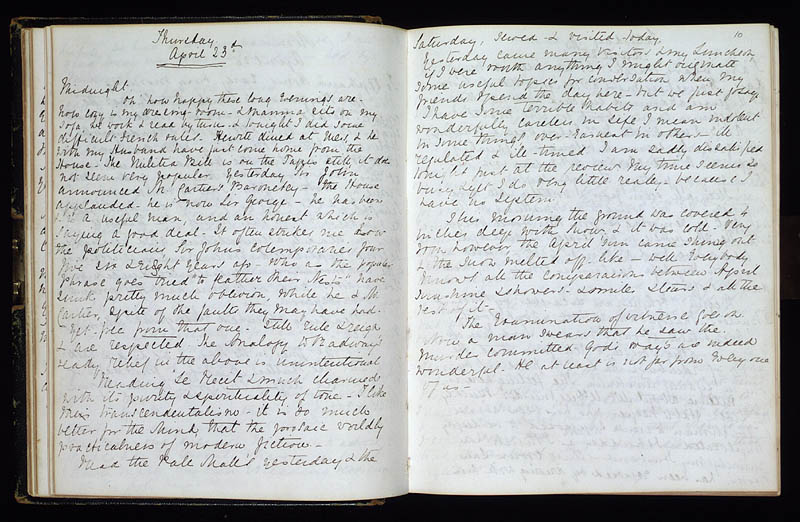

Diarist

Lady Macdonald began keeping a diary soon after Canada’s first Dominion Day (1 July 1867), and wrote over 100 individual entries during the years 1867–72, 1875 and 1883. The earliest entries are alive with her excitement of being at the centre of Ottawa’s political and social life. She jokes that “[h]ere — in this house — the atmosphere is so awfully political — that sometimes I think the very flies hold Parliaments on the Kitchen Table cloths!” (5 July 1867). A year later, Lady Macdonald more thoughtfully reflects on her husband’s demanding career and its impact on her home. In her entry for 19 September 1868, for example, she notes “a trying & rather Invalid week. [...] Storms in the Privy Council atmosphere always agitate home air & living so completely as I do — in my Husband’s circle of Interests, I cannot help being influenced by the Political Barometer.”

Although the diary does not contain political secrets, or Lady Macdonald’s opinion about significant events such as the Pacific Scandal , it does offer insight into the domestic world of the 19th-century Canadian matron of social standing in her community. In addition to her basic housekeeping efforts “[t]o make [her husband’s] home cheery & pleasant” (11 January 1868), Lady Macdonald’s days were busy with public appearances and philanthropic and social commitments. Almost a year after her marriage, she records a typical day in her life as prime minister’s wife: “after morning service I dressed for my ‘day’ & belonged to the Public until six o’clock. First came Mrs. Bronson on Orphans’ Home Matters, & then my luncheon party and callers afterwards” (5 February 1868).

Lady Macdonald also used her diary to keep track of her extensive reading of biography, history, travel accounts, religious texts and magazines. Her discussions about these works with her husband, her mother and a reading group of women illustrate the practice by which 19th-century women sought to understand and speak about the politics of their world. It was her reading of such prominent prison reformers and abolitionists as Elizabeth Fry and William Wilberforce that shaped Lady Macdonald’s understanding of principles of justice, punishment and social reform. At the conclusion of the “deeply, fearfully interesting” trial of Patrick Whelan, the suspected Fenian sympathizer charged and convicted with the murder of Thomas D’Arcy McGee (see The Assassination of Thomas D’Arcy McGee), she pauses for a moment to contemplate the value of capital punishment: “They tell me [Whelan] cannot feel!! Cannot feel!! [...] Can a living, healthy man — young & active in whose veins the blood bounds quick & strong, can he know he shall be sentenced to hang by [the] neck, till his Body be dead […] and not feel! If men then do not feel, then capital punishment is useless murder” (19 September 1868).

Travel Writer

Lady Macdonald travelled extensively during her life, covering great distances and using different forms of transportation. In addition to ship, train, canoe and toboggan, she experienced the novelty of riding a bicycle and even driving in a car during the later years of her life. She published two sketches about her travels aboard the Canadian Pacific Railway (CPR) — “By Car and by Cowcatcher,” and “An Unconventional Holiday” — as well as an account of her fishing trip on the Restigouche River in northern New Brunswick, titled “On a Canadian Salmon River.”

Unlike the moralistic tone of the diary, Lady Macdonald’s travel sketches showcase a keen wit and a perceptive mind. Her harrowing ride through the Rockies on the cowcatcher of a train (a device attached to the front of a train to clear obstacles) is laugh-aloud funny, although much less amusing to the unfortunate pigs that wandered out onto the track. In “By Car and by Cowcatcher,” she deadpans the fate of the pigs: “There was a squeak, a flash of something near, and away we went. [...] The Secretary [Joseph Pope] averred that the body had struck him in passing; but as I shut my eyes tightly almost as soon as the pigs appeared, I cannot bear testimony to the fact.”

Far more sobering is Lady Macdonald’s depiction of the Aboriginal persons she encounters during her travels aboard the CPR. Her support of the Indian Act (1876), and her husband’s project to assimilate Canada’s First Nations is evident through her reference to a “wild people, which civilization is fast ‘improving’ off the face of the earth altogether.” But what Lady Macdonald identifies as the civilizing success of her husband’s undertaking will read as a devastating betrayal by many 21st-century readers.

Her portrayal of “[t]wo delightful Sioux boys [who] were brought to Government House by the priest who is educating them at his Mission School” whose “bright black eyes alone gave sign of life as, during a long visit, they stood perfectly rigid in brand-new broad-cloth, never stirring a finger” unconsciously acknowledges the residential school system that disrupted and destroyed generations of Aboriginal families, their traditions and their languages. And her notice of “a low, long, horrid-looking wall of neatly-piled, bleached [buffalo] skulls, gathered from the prairie” is grisly evidence of the further impact of European settlement on traditional Aboriginal hunting practices (see Buffalo Hunt), as well as the ecological cost of building the CPR through buffalo territory.

Political Writer

Lady Macdonald is credited as the writer of two anonymously published political sketches (“Canadian Topics” and “Men and Measures in Canada”) as well as a political and biographical sketch that pays tribute to the life of Sir John A. Macdonald (“A Builder of the Empire”). Full of political detail and opinion, these sketches reveal a much different Lady Macdonald than the one who appears in her diary and travel writing. The narrator speaks knowledgeably about specific details of “the most hotly contested, the most exciting, and the most interesting altogether” general election of 1886. She also writes critically about the trade oversight of Canada’s inshore fisheries that “must absolutely be protected from invasion [because] Americans seem to have a national aptitude for destroying, or rather exterminating, game and fish.”

The sketch about Sir John A. is a complex piece of work in which Lady Macdonald (writing as “Macdonald of Earnscliffe”) situates herself as an expert eyewitness to the personal and political lives of the former prime minister. When referring to Sir John A.’s thoughts on Confederation, for example, she asserts that “[the] fixed idea of a united empire was his guiding star and inspiration. I, who can speak with something like authority on this point, declare that I do not think any man’s mind could be more fully possessed of an overwhelmingly strong principle than was this man’s mind of this principle.” Published a few years after Sir John A.’s death, this sketch positions Lady Macdonald as a key voice in speaking about him and his life as politician.

Later Life

In 1891, Lady Macdonald was a 55-year-old widow who found herself on the outside of Ottawa’s political world. After accepting a peerage appointment from Queen Victoria, the new Baroness of Earnscliffe (or Macdonald of Earnscliffe) witnessed the slow but steady decline of her husband’s Conservative Party. Soon after Wilfrid Laurier’s Liberal victory in 1896, the Baroness permanently relocated her household to England. Settling in Eastbourne, she and Mary spent the next two decades wintering in popular European destinations, at one point finding themselves stranded in Switzerland at the outbreak of the First World War. Agnes Macdonald died a few years later in Eastbourne, after a series of strokes, on 5 September 1920.

Significance

Lady Agnes Macdonald may be considered one of the Mothers of Confederation for her commitment to nation building. She could not vote or hold office, and therefore could not directly contribute to the political processes and policies that created the Dominion of Canada. But she was an informed and engaged observer of her world, and recorded her insights and experiences in her diary and her published travel and political sketches. Clearly, Lady Macdonald wished to preserve her work. At one point, she anxiously wrote to Joseph Pope that “[m]y only fear is that letters, papers and diaries of mine should get astray. Any of these [...] must, when possible, be sent to me.” Such concern reveals her awareness, or indeed her hope, that a future audience would one day read her narratives about the new nation of Canada.

Share on Facebook

Share on Facebook Share on X

Share on X Share by Email

Share by Email Share on Google Classroom

Share on Google Classroom