The term franchise denotes the right to vote in elections for members of Parliament, provincial legislatures and municipal councils. The Canadian franchise dates from the mid-18th-century colonial period. At that time, restrictions effectively limited the right to vote to male property holders. Since then, voting qualifications and the categories of eligible voters have expanded according to jurisdiction. These changes reflect the evolution of Canada’s social values and constitutional requirements.

Historical Background

Pre-Confederation

As the colonies that came to form Canada in 1867 became self-governing, they eventually gained control of defining who could vote. (See Representative Government.) As a result, the rules differed substantially between the colonies. All were heavily influenced by English law; the franchise was restricted to men with property assets of a certain value, and Catholics were prevented from voting. However, the unique circumstances of each of the colonies meant that these rules could not simply be transferred directly.

For most of the pre-Confederation period, most colonies required property ownership to qualify to vote. The amount of property required varied over time and in the different colonies. In Nova Scotia, there were no property qualifications between 1851 and 1863. New Brunswick got an elected assembly in 1785. (See Responsible Government.) It initially chose to extend the franchise to those without property; but it introduced strict property restrictions in 1791. New Brunswick also restricted Catholic people from voting. This disenfranchised the Acadians. Both Upper and Lower Canada (present day Ontario and Quebec) maintained property restrictions throughout this period. Prince Edward Island (PEI) was an exception, as few residents on the Island owned land. (See PEI Land Question.)

Most colonies initially followed the British practice that required eligible voters to take an oath of loyalty. These oaths explicitly renounced papal authority, which disenfranchised Catholics. The references in oaths to the “Christian faith” also excluded Jewish people. In addition, some religious communities, such as Quakers, were prevented by their faith from taking oaths. Nova Scotia abolished religious qualifications in 1789; New Brunswick did so in 1810. PEI enfranchised Quakers in 1785. It allowed non-Protestants to vote in 1830. Upper and Lower Canada had no religious exclusions. However, until 1833, groups such as Quakers could not vote because of the need to take oaths. (See also Voting in Early Canada.)

Finally, women voted regularly in Lower Canada from 1791 until 1849. There are reports of women voting occasionally in Nova Scotia and New Brunswick. However, for most of this period and in most of the colonies only men could vote. (See also Women’s Suffrage.)

Post-Confederation

With Confederation in 1867, the definition of the franchise was left to the provinces. This meant that eligibility to vote in a federal election could vary from one province to another. All provinces, however, restricted the franchise to male British subjects who were at least 21 years old who met a property qualification.

For the first 50 years after Confederation, the Liberal and Conservative parties manipulated the federal franchise in a blatantly partisan fashion. At various times until 1920, the federal franchise was based either on the electoral lists drawn up by the provinces for provincial elections; or on a federal list compiled by enumerators appointed by the governing party in Ottawa. Until 1885, the vote was based on provincial law. Because of this, elections were staggered; they could be held on different days in different places. Voters in one constituency might already know which party was likely to form government. Given the importance of patronage in this era of Canadian politics, this created a powerful incentive to vote for the winning party.

Canada’s most controversial franchise legislation was passed by Parliament during the First World War. The Wartime Elections Act and the Military Voters Act of 1917 enfranchised female relatives of men serving with the Canadian or British armed forces; as well as all servicemen, including those under 21 and status Indians. It also disenfranchised conscientious objectors and British subjects naturalized after 1902 who were born in an enemy country or who spoke an enemy language. Prime Minister Robert Borden’s Conservative government openly admitted that the legislation was biased in its favour. The 1917 election results proved that they were right. Such abuses and shifts in the policies governing the right to vote ended in 1920 with the adoption of the Dominion Elections Act. It established a standard Dominion-wide franchise.

Women

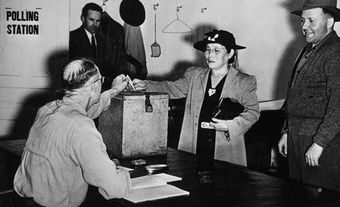

Some instances were recorded of women voting in Canada until 1849. Despite this, Canadian women were systematically and universally disenfranchised. Apart from the temporary and selective right to vote granted to women under the Wartime Elections Act in 1917, women were first granted the right to vote federally in 1918.

In 1916, Manitoba became the first province to enfranchise women for provincial elections. Quebec was the last province to do so, in 1940. In 1951, the Northwest Territories became the last territory to grant women the vote. (See also Women’s Movement; Women’s Suffrage.)

Black Canadians

During the period of Black enslavement in Canada, from the early 1600s until its abolition on 1 August 1834, Black persons were legally deemed to be chattel property (personal possessions). As such, Black people were not considered to be persons; they therefore did not possess the rights or freedoms enjoyed by full citizens. These included protections under the law and involvement in the democratic process. (See Black Voting Rights in Canada.)

Black Canadians secured some rights and freedoms as their social status changed from enslaved persons to British subjects. This occurred with the gradual abolition of enslavement, during the period 1793 to 1834. (See also Chloe Cooley and the Act to Limit Slavery.) As British subjects, Black Canadians were technically entitled to all of the rights, freedoms and privileges that status carried. However, because of their skin colour, they faced racism and discrimination. As a result, their civil rights and civil liberties were limited. The rights and freedoms of Black women were further restricted by virtue of their sex. Most women did not gain suffrage at the federal level until 1918 and between 1916 and 1940 at the provincial level. (See Women’s Suffrage.)

Black men had the right to vote if they were naturalized subjects and owned taxable property. Until 1920, most colonies or provinces required eligible voters to own property or have a taxable net worth. This practice excluded poor people, the working class and many racialized minorities. Black Canadians were not prohibited by law from exercising the right to vote. However, public sentiment against extending the franchise to Black people did exist, and local conventions did prevent Black persons from voting.

Asian Canadians

Asian peoples first began arriving in Canada in the 19th century. From that point through much of the first half of the 20th century, most Canadians of Asian heritage were denied the right to vote in federal and provincial elections. Federally, the Electoral Franchise Act (1885) explicitly denied Chinese Canadians the right to vote. In 1898, new legislation extended the franchise to Asian voters.

In 1920, the Dominion Elections Act said that if a province discriminated against a group by reason of race, that group would also be excluded from the federal franchise. This meant that British Columbia residents of Chinese, Japanese and South Asian background lost their right to vote in national elections. (Saskatchewan also disenfranchised the Chinese.) In 1948, the federal government voted to repeal this section of the Dominion Elections Act. However, the change did not come into effect until 1 April 1949. Japanese Canadians also regained the right to live anywhere in Canada, which was initially restricted following their internment during the Second World War. Only a week earlier, the British Columbia government had amended the Provincial Elections Act to enfranchise all racial groups in the province; with the exception of Doukhobors. The last statutory disenfranchisement of Asian Canadians was removed.

Indigenous Peoples

Indigenous peoples in Canada consist of First Nations, Inuit and Métis communities. Each has a different history of voting rights. (See also Indigenous Suffrage; Indigenous Women and the Franchise.)

First Nations

Through a process called enfranchisement, First Nations people could give up their Indian status and vote in federal elections as early as 1867. (A status Indian is an individual who is registered under the Indian Act. It is a legal recognition of a person’s First Nations heritage. It affords certain rights, such as the right to live on reserve land.) The term enfranchisement was used for those who gave up their status by choice. It also applied to the much larger number of Indigenous men and women who lost status automatically for one of several reasons. These included the loss of status upon completion of university and upon the marriage of a woman to a non-status man. (See Women and the Indian Act.) First Nations men who served during the Second World War gained the franchise without having to relinquish status. But they could only continue to vote if they moved from their homes on reserves.

In the 1920s, the federal government imposed elected leadership structures on top of traditional forms of governance on reserves. A theoretical enfranchisement occurred under this imposition. For example, bands elected leaders that dealt with the federal government. However, this system was not well received and was often boycotted. Many communities did, and still do, have two chiefs: the elected chief, who is officially recognized by government, and a traditional chief, who is often determined by heredity.

Non-status Indians eventually received full voting rights at the provincial level. This started with British Columbia in 1949 and ended with Quebec in 1969. The federal franchise was first extended to non-status Indians in 1950. The franchise fully extended to status Indians in 1960 under the John Diefenbaker government. This was 12 years after a parliamentary committee recommended that First Nations be fully enfranchised. (See also Indian Act; Enfranchisement.)

Inuit

The Dominion Franchise Act (1934) disqualified Inuit, along with status Indians, from voting in federal elections. Most Inuit were enfranchised in 1950. But they were unable to vote for various reasons. Inuit were rarely enumerated (added to official lists of people entitled to vote) and ballot boxes were not brought to Inuit communities in the Arctic until the 1962 general election.

Métis

The Métis have never experienced restrictions on their right to vote. Métis have by and large not been covered by treaties or statutes such as the Indian Act. Therefore, no legal means have existed by which to disenfranchise them.

Charter Rights

Canada now has a virtually universal franchise at both the provincial and federal levels. Section 3 of the Canadian Charter of Rights and Freedoms states that, “every citizen of Canada has the right to vote in an election of members of the House of Commons or of a legislative assembly and to be qualified for membership therein.” This provision paved the way for the successful court challenge to the disenfranchisement of judges and persons with intellectual disabilities. The courts struck down the denial of the vote to these groups by accepting the inclusiveness of Section 3 of the Charter. They also found under Section 1 of the Charter that such limitations could not be justified as “reasonable” in a “free and democratic society.”

In challenges to the Canada Elections Act between 1986 and 2002, prison inmates in Manitoba and Ontario met with mixed success in their various Charter challenges to the denial of their right to vote. The question was eventually resolved in the prisoners’ favour in a 5 to 4 decision of the Supreme Court of Canada (Sauvé v. Canada, 2002). As a result, all restrictions on prisoners’ voting rights at both the federal and provincial levels were struck down.

The courts have generously interpreted the right to vote under Charter challenges. Nonetheless, one restricted category of otherwise eligible voters remained. In 1993, the Canada Elections Act was amended to grant the vote to Canadians living abroad for up to five years at a time. The exclusion of Canadians living abroad for more than five years at a time was subject to a Charter challenge in the Ontario Court of Appeal; it ruled against the challenge. However, in January 2019, the Supreme Court ruled that Canadian citizens can vote in federal elections regardless of how long they have lived outside the country.

National Register of Electors

A National Register of Electors was established in 1997 to prepare voters’ lists. It replaced door-to-door enumerations at election time. These were expensive, time-consuming and labour-intensive. The computerized registry is maintained in Ottawa by Elections Canada. It is an independent and non-partisan agency that administers federal elections. (See Chief Electoral Officer.) The registry is updated with information (e.g., name, address, sex, and date of birth of Canadians eligible to vote) supplied by provincial and federal agencies; these include Vital Statistics registrars, the Canada Revenue Agency, Citizenship and Immigration Canada and Canada Post. The relevant information on electors contained in the register is in turn shared with provincial, territorial and municipal electoral officials for their voters’ lists.

Significance

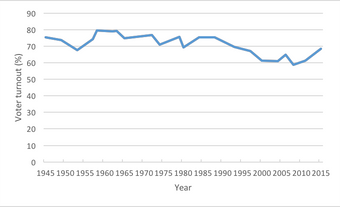

The right to vote is one of the most fundamental rights of citizenship. In Canada, the right to vote has gone from being held by a relatively small group — Protestant men who owned property — to being widely held. The development of the franchise in Canada thus reflects Canada’s maturation as a liberal democracy.

See also Voting Rights Collection; Women’s Suffrage in Canada; Women’s Suffrage Timeline; Indigenous Suffrage in Canada; Indigenous Peoples and the Fight for the Franchise; Black Voting Rights in Canada; Canadian Electoral System.

Share on Facebook

Share on Facebook Share on X

Share on X Share by Email

Share by Email Share on Google Classroom

Share on Google Classroom