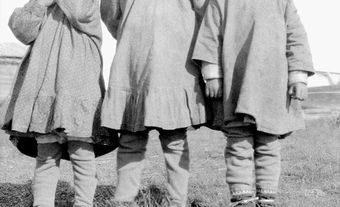

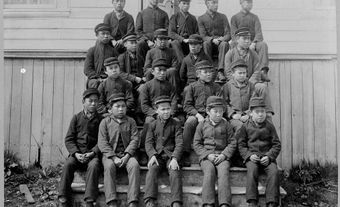

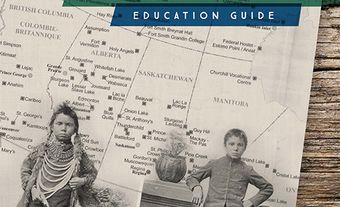

Church-run schools for Indigenous children were created in Canada in the 1600s. In 1883, the Canadian government funded and helped establish more church-run schools. The goal was to assimilate Indigenous children into the dominant white, Christian society. By the time the last residential school closed in 1996, more than 150,000 First Nation, Métis and Inuit children had been forced to attend against their will and the wishes of their parents. Many children were physically, emotionally and sexually abused at the schools. Thousands died. The multigenerational social and psychological effects of the schools have been devastating and ongoing. The federal government and churches have apologized for what is now widely considered a form of genocide. (See also Genocide and Indigenous Peoples in Canada.)

Knowledge of what happened at the schools is an essential part of reconciliation and healing. Many children’s books have been written about residential schools as part of that essential effort. This list includes titles for toddlers to preteens. Together, these books explore a variety of themes related to residential schools, including intergenerational trauma, language revitalization, commemoration and the power of resistance.

1. Phyllis’s Orange Shirt by Phyllis Webstad, illustrated by Brock Nicol (2018). Recommended for ages 4 to 6.

Every 30 September, Canada observes Orange Shirt Day to commemorate the victims and survivors of residential schools. Orange Shirt Day was inspired by the story of Phyllis Webstad. She was given an orange shirt by her grandmother for her first day of residential school. The book tells the story of how the shirt was taken by the nuns. This theft came to symbolize all that was taken from Indigenous children, families and communities. With a gentle rhyming tempo, the book speaks of Phyllis’s time at school.

2. Shi-shi-etko by Nicola Campbell, illustrated by Kim Lafave (2005). Recommended for ages 4 to 7.

The story begins with a little girl named Shi-shi-etko waking her mother and announcing that it is just four days until she will have to leave to attend residential school. They walk to the creek, where Shi-shi-etko’s mother explains that, despite all that will be endured at the school, she must always remember the land and their traditional way of life. As each day is counted down, Shi-shi-etko’s father, grandmother and cousins remind her of more that needs to be remembered. The book powerfully portrays all that residential schools sought to destroy.

3. Kookum's Red Shoes by Peter Eyvindson, illustrated by Sheldon Dawson (2015). Recommended for ages 4 to 8.

Kookum, the Cree word for “grandmother,” equates her happy early life to that of Dorothy in The Wizard of Oz. She even has a pair of red shoes like Dorothy’s. But one day, a truck arrives in a tornado of dust and steals her and other children away to a scary place far from home: the residential school. Cruel nuns mistreat them and enforce rules like not speaking their language. When they are allowed to go home for the summer, the girl finds her family different and sad and discovers that her treasured red shoes, like her, no longer fit. The book talks about the power of healing and reconnecting with culture and community.

4. Arctic Stories by Michael Kusugak, illustrated by Vladyana Krykorka (1998). Recommended for ages 4 to 8.

Set in 1958, the book offers three stories about a lonely 10-year-old Inuit girl named Agatha. In the first story, Kusugak augments his personal experiences with sensational tales, such as Agatha saving her village from a black airship. In the second story, Agatha learns of the natural world by feeding and befriending birds. In the final story, she is forced from her family and home to attend residential school. She finds the nuns and priests cruel and uncaring but nonetheless saves a priest who, while showing off, has fallen through the ice.

5. When We Were Alone by David A. Robertson, illustrated by Julie Flett (2016). Recommended for ages 6 to 8.

The story is told from the perspective of a young girl named Nósism, who is helping her grandmother, Kókom, in the garden. Nósism asks her why she always wears colourful clothing and her hair in long braids, speaks Cree and loves being with her family. The grandmother responds to each question by explaining that all of this was forbidden when she was in residential school. Kókom adds that she and the other children always found quiet ways of rebelling and remembering their culture. The story celebrates the importance of retaining traditions once lost to residential school.

6. When I Was Eight by Christy Jordan-Fenton and Margaret Pokiak-Fenton, illustrated by Gabrielle Grimard(2013). Recommended for ages 6 to 9.

An Inuit girl named Olemaun explains how, at the age of eight, she knows how to live on the land and with the outsiders with whom her family occasionally interacts. Wanting to learn to read, she nags her father to attend the outsider school until he reluctantly agrees. At the school, her Inuit name is replaced by an English one, Margaret. Her braids are cut off and she is made to wear uncomfortable clothing. Along with the other children, she is forced to work more than study and is treated cruelly. Yet, the resilient Olemaun teaches herself to read.

7. The Train by Jodie Callaghan, illustrated by Georgia Lesley (2020). Recommended for ages 6 to 9.

A young Mi’kmaq girl named Ashley is on her way to school when she meets her great-uncle near an abandoned railway track. When she asks why he looks so sad, he begins to tell a story from his past. When he was young, a train came to take him and other children to residential school. He tells stories of his painful experiences as Ashley struggles to understand how something so terrible could have happened. He explains that he is waiting for all that was lost to return someday. Ashley promises to wait with him.

8. Stolen Words by Melanie Florence, illustrated by Gabrielle Grimard (2017). Recommended for ages 6 to 9.

A happy seven-year-old girl skips home with a dreamcatcher that she made at school. She asks her grandfather how to say “grandfather” in Cree, but he sadly responds that he can’t remember the word. He explains how he and other children were taken from their homes and crying mothers by angry men and women to be placed in schools where the old words were stolen. She gives him the dreamcatcher to help him remember his words. The next day, she speaks a few words of Cree to her grandfather and shows him a book entitled Introduction to Cree. Together, they begin to remember the stolen words. (See also Indigenous Language Revitalization in Canada and Indigenous Languages in Canada.)

9. As Long as the Rivers Flow by Larry Loyie with Constance Brissenden, illustrated by Heather D. Holmlund (2005). Recommended for ages 8 and up.

The story is set in northern Alberta in 1944. A 10-year-old Cree boy named Lawrence is enjoying a summer of fun adventures and finds a baby owl. He learns how to tend to the owl and then, on a family journey on the land, learns traditional knowledge and respect for the natural world. Lawrence grows concerned, though, when he hears adults talking about him having to attend a distant residential school in the fall. In September, a truck arrives and Lawrence and other crying kids are taken away by fearsome strangers dressed in black.

10. Fatty Legs by Margaret-Olemaun Pokiak-Fenton and Christy Jordan-Fenton, illustrated by Liz Amini-Holmes (2010). Recommended for ages 9 to 11.

Fatty Legs tells the story of an eight-year-old Inuit girl named Olemaun, later called Margaret at residential school. She is tormented by a nun who the kids call “Raven.” (See also Raven Symbolism.) To humiliate Margaret, Raven forces her to wear baggy red stockings that make her legs look fat instead of the trim gray ones worn by all of the other girls. Margaret’s determined effort to retain her dignity before the actions of the nun and the taunts of the other kids demonstrates the power of resistance and resilience.

Share on Facebook

Share on Facebook Share on X

Share on X Share by Email

Share by Email Share on Google Classroom

Share on Google Classroom

.jpg)