Background

The British victory on the Plains of Abraham in September 1759 placed the city of Quebec under British rule. Montreal capitulated the following year. A temporary military regime was set up pending the outcome of negotiations between Britain and France.

By the terms signed on 8 September 1760, the British guaranteed the people of New France the following: immunity from deportation or maltreatment; the right to depart for France with all their possessions; continued enjoyment of property rights; the right to carry on the fur trade on an equal basis with the British; and freedom of religion.

With the Treaty of Paris, signed on 10 February 1763, the colony of New France became a British possession. Shortly thereafter, Britain’s newly acquired territories were politically organized through the Royal Proclamation of 1763.

British Administration

Under the policies laid out in the Royal Proclamation of 1763, the governor became the authority in the new province of Quebec. The governor was appointed by the British government and subject to its directives. English criminal and civil law replaced French law. The imposition of the oath of allegiance for public employees excluded Catholics from public positions.

These seemingly assimilative policies quickly clashed with the realities of a French Catholic society. British governors were the first to renounce these policies. This was reflected in the provisions of the Quebec Act in 1774. The British Parliament expanded the area of the Province of Quebec, re-established French civil law and authorized the collection of tithes. These changes allowed them to win the acceptance of the country’s ruling classes, namely the Catholic clergy and the seigneurs.

Acceptance of British Rule

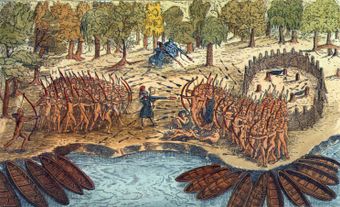

History is filled with military conquests that were never accepted by the conquered, and which gave rise to ongoing resistance, violent or otherwise. The British conquest of New France, however, did not kindle staunch resistance in Canada.

The Seven Years’ War had been long and difficult and was accompanied by vast destruction. The conquest brought a degree of peace and stability that had long been absent. It was therefore relatively well accepted by those who were subjected to it. In the early 20th century, André Siegfried wrote that rarely had foreign domination been so completely accepted by those subjected to it. A number of factors contributed to this.

New France Was Conquered, But Also Abandoned

Abandonment occurred as well as conquest. France could have tried to win Canada back through diplomatic negotiations. After all, it had done so following Sir David Kirke’s conquest of Quebec in 1629, even though this involved giving up its West Indian colonies. But with the Treaty of Paris in 1763, France chose to abandon Canada. This was mainly because the colony had cost more than it had returned.

France also made no subsequent attempt to regain Canada. Even at the height of his power, Napoleon shed the last piece of the French Empire in America by selling it to the Americans in the form of the Louisiana Purchase. This total retreat by France was emotionally difficult for its colonial subjects to accept. It forced Canadians to come to terms with the existing balance of power.

Absence of Nationalism

The Conquest took place prior to the French Revolution (1789–99) and before the birth of the concept of nationalism. The 18th century was a period when monarchs exchanged territories like commodities. Nations defined themselves by religion and common allegiance to a sovereign, not by the language or culture of their inhabitants or by the social and political affiliations that came with it.

In the capitulation treaties of Quebec and Montreal and the Treaty of Paris, not a single word was mentioned about the French language. However, these treaties did guarantee the free exercise of religion.

The Catholic Perspective

The conquered community of Canada was Catholic. The clergy were among the few leaders who remained after the French merchants and colonial administrators had left. In the years after the French Revolution (1789–99), many Canadians saw the Conquest as a divine rescue from revolutionary chaos — an idea that was long influential. Later generations also tended to see the Conquest positively, as it led to religious tolerance and representative government.

The Church was well treated by the conquerors, and thus preached respect for the established authority. This was true even in difficult times, such as during American invasions in 1775 and 1812, as well as the 1837 rebellion and the 1917 conscription crisis. However, Canadians were less welcoming of the ethnic dualism that came from introducing British government and immigration into an established French colony.

Improved Conditions Under British Rule

The final years of the French regime were marred by widespread corruption and many unpleasant memories. The Conquest actually resulted in a peace that New France had hardly known. The conquerors also granted the conquered conditions that were enviable by the standards of the time.

Among the British, there were two competing perspectives on how to handle the Conquest: impose their yoke and reinforce the conquest; or offer concessions and make life under British rule more acceptable to Canadians.

The former attitude (which prevailed in Ireland) was evident in the Royal Proclamation of 1763 in the form of the oath of allegiance and the imposition of British civil law. It would also resurface in the Durham Report in 1839. However, this approach always failed. For example, the English unilingualism that was imposed following the Durham Report was abolished only a few years later.

The latter view was evident in the attitudes of the first governors (James Murray and Guy Carleton) and found legal expression in the Quebec Act of 1774. The Quebec Act was an exceptionally liberal measure at the time in that it granted Canadian Catholics a freedom that British Catholics did not obtain until 1829. This measure, which rallied clergy and seigneurs to the British crown, had its origin in the apprehended rebellion of the American colonies.

Canadians refused to join the American Revolution. If they had, it is doubtful they would have survived total Americanization. British military strength was long viewed as a guarantee against American invasion.

The conquerors also brought with them new ideas that constituted real progress. It was as a conquered people that French Canadians were initiated into the more advanced systems of parliamentary democracy and criminal law. Those seeking a more democratic political regime from the British governors cited England as an example to follow. This vision would predominate in French Canada until the early 20th century, after which the perspective changed.

French-Canadian Nationalism in the 20th Century

French Canadians resisted the notion that they were obliged to take part in defending the British Empire. The Boer War and the 1917 conscription crisis caused them to see Britain as a threat rather than a security against the decreasing threat of American expansionism. Britain’s treatment of Francophone minorities outside Quebec also suggested that British tolerance stopped at the Quebec borders.

The British Empire declined after 1918 and particularly after 1945, when the Church’s hold over Quebec society also began to loosen (see Quiet Revolution). The perspective implied by the motto “Je me souviens. Né sous le lys, j’ai grandi sous la rose,” (“I remember. Born under the lily I grew up under the rose.”) gradually faded. In its place arose a pessimistic reading of French-Canadian history. The Conquest came to be seen as a catastrophic event responsible for a long decline that would only be rectified by independence (see French Canadian Nationalism).

Legacy and Significance

Some modern historians, such as Michel Brunet, have seen the Conquest as a disaster for French Canadians. Brunet pointed to the monopolization of the higher levels of government and business by English-speaking newcomers as evidence that the Conquest made French Canadians second-class subjects. Others, such as Fernand Ouellet, have downplayed any harmful effects, pointing to a fairly continuous development of economic foundations, institutions and culture.

For the Indigenous peoples, the end of Anglo-French hostility meant a fateful decline in their importance as allies and warriors, making them increasingly irrelevant to White society.

The Conquest remains a subject of debate. Its influence is also evident in the American Revolutionary War, which was possible only when the American colonies no longer needed British protection from French forces in North America.

Share on Facebook

Share on Facebook Share on X

Share on X Share by Email

Share by Email Share on Google Classroom

Share on Google Classroom