This article was originally published in Maclean's Magazine on April 8, 1996

Lemieux, Mario (Profile)

A small crowd had gathered under the stands at the ThunderDome in St. Petersburg, Fla., waiting excitedly to meet Mario Lemieux after a game between his Pittsburgh Penguins and the Tampa Bay Lightning. As always, Lemieux was well turned out in a tailored jacket and pants, with his dark hair slicked back from a post-game shower. He did not, however, look very comfortable making casual chat with the well-wishers. But as he finished up, his eyes brightened at the sight of David Boulet, a 12-year-old from St. Petersburg whom he had met earlier in the day. Boulet and Lemieux have something in common: Hodgkin's disease, a cancer of the lymphatic system. Pale and thin from months of chemotherapy and radiation treatment, the boy smiled when Lemieux broke away from the crowd to say hello. They talked quietly for a few minutes, after which the six-foot, four-inch, 220-lb. hockey player straightened up and rested a hand on Boulet's shoulder. "You're going to be fine," Lemieux assured him. "If I can do it, you can, too."

The scene was a public relations dream - except that Lemieux has no interest in public relations. In an age of headline-hungry athletes, the 30-year-old Montrealer skates the other way, choosing privacy over celebrity, even though it diminishes his income and often deprives him of his professional due. Timing and geography have also dulled the brilliance of a career in which Lemieux has so often made the play but missed the glory. He is a once-in-a-generation talent whose generation somehow produced two - and the Great One, Wayne Gretzky, arrived in the National Hockey League five years before him. Lemieux works his magic in the media backwater of Pittsburgh, and although he has led the Penguins to two Stanley Cup titles - key components of any legend's résumé - most Americans missed those triumphs because they occurred before the NHL had a U.S. network TV deal. And this season, his heroic return to the NHL from cancer and back problems has been overshadowed on the American sports landscape by the second coming of basketball icons Michael Jordan and Magic Johnson.

But as the regular season wraps up and the playoffs approach in mid-April, there is no hiding the fact that Mario Lemieux has fashioned a remarkable comeback story. Take last week, when Lemieux - going head-to-head against Gretzky and the St. Louis Blues - tallied five goals and two assists to carry the Penguins to an 8-4 victory (Gretzky had a single assist). The goals propelled Lemieux past Guy Lafleur into 11th place on the NHL's career points list, lengthened his lead in the league scoring race this year, and left little doubt that, like Jordan in hoops, he has returned to dominate hockey as if he had never been away. To complete the tale, Lemieux's scoring blowout of the Blues came on his first night back since his wife, Nathalie, gave birth to the couple's third child, Austin, three months prematurely. Mother and son, Lemieux says, "are doing great."

So is Mario, especially considering that he had been off skates for the equivalent of two full seasons since being diagnosed with Hodgkin's in January, 1993. The man the press dubbed the Magnificent One (his teammates simply call him Big Guy) missed 20 games that year while undergoing radiation treatments. He sat out three-quarters of the next season because of complications following surgery to repair a herniated muscle in his back, and later because of another back injury that was so debilitating he was often unable to tie his own skates. That crippling pain, coupled with strength-sapping anemia caused by the radiation treatments, forced him to miss the entire 1994-1995 campaign.

But he is back with a vengeance this year, leading the Penguins to the best record in the tough Eastern Conference and into serious contention in the upcoming Stanley Cup playoffs. They will not be the favorites: that burden falls on the high-flying Detroit Red Wings, who will face a stiff challenge in the Western Conference from the Colorado Avalanche. The Penguins, meanwhile, served notice in the East last week by clobbering their closest competitor, the New York Rangers - without Lemieux in uniform. Pittsburgh's second line - centre Ron Francis between the wild and crazy Czechs, Jaromir Jagr and Petr Nedved - is one of the most potent scoring lines in NHL history. But a healthy Lemieux is still the key to the Cup. "The number 1 reason for us being in first place is because of 66," says Penguins coach Eddie Johnston, referring to Lemieux's jersey number. "He's having an incredible year and he makes everyone around him better."

If the public does not fully appreciate his talents, Lemieux himself is partly to blame. At his request, his agents and the team's public relations staff politely but firmly turn down all but a few interview requests and, even when Lemieux does sit with a reporter for any length of time, he deliberately reveals little of himself. "That is the way I want it," he told Maclean's. "The less people know about me, the better."

Still, his teammates and old friends say he pays too high a price for his shyness. "There are athletes who get bigger accolades than they deserve just because they are in the public eye all the time, and that's not fair," says Rick Tocchet, an ex-Penguin who now plays for Boston. "On pure hockey ability, he's probably the best player in the history of the game next to Wayne, and Wayne's played six or seven more years." Such respect comes even from the man who casts the biggest shadow. "I think this season has been his best performance, and not just because he's coming back," says Gretzky. "The game is better now than it was four or five years ago. The players play a more defensive style now, the goaltending is better. His performance in that style of hockey is amazing."

Harry Neale, the former Vancouver Canucks coach who now works as an analyst on Hockey Night in Canada, puts it most eloquently. Lemieux, he says, "is one of the half-dozen or so players in history who are in the NHL only because there is no better league for them to go to."

That he is still playing at all is a tribute to medical science and his own love of the game. Lemieux had been plagued by back injuries for years, and twice had surgery to relieve the pain. A dangerous infection set in after the first surgery, causing him to miss still more games. In January, 1993, he found a lump on his neck that turned out to be an enlarged lymph node, and a biopsy revealed Hodgkin's disease - fortunately, in its early stages. After six weeks of radiation treatment, he returned to the ice in time to capture the league scoring title once again.

Lemieux's current comeback began a year ago, when he started working with trainer Tom Plasko on a program that strengthened his back, increased his overall flexibility and left him more fit than he had ever been. The program has enabled him to play without pain for the first time in years, so he makes time after every practice to lift weights or ride the stationary bicycle. "I feel better, physically and mentally," Lemieux says, wiping the sweat off his face with a towel after working out at the Penguins' practice facility in suburban Canonsburg, Pa., 30 km south of Pittsburgh. Then, with a chuckle, he adds: "Maybe I should have been doing that earlier in my career."

The truth is that Lemieux has fashioned his brilliant career even while being notoriously unfit by NHL standards. His willingness to work now has impressed his teammates. Standing outside the training room where Lemieux was going through his paces, teammate Francis said it was not as if the Penguins' captain had anything to prove. "He has already shown people what he could do, he had won the Stanley Cup twice and he had made a lot of money," says Francis. "He could have said goodbye, but he wanted to come back, to play. That's what makes the great players great - they absolutely love the game." Opponents have been equally amazed. "It's one thing to come back from a serious injury like he had," says Cam Neely, a rugged Boston Bruins winger who has also been plagued with injuries. "But it's another to beat cancer, be off skates for that long and then come back and play at his level."

Lemieux himself is not surprised. He has always been able to rely on the sublime talent he first showed on the streets of Ville Emard, the working-class Montreal neighborhood where he grew up. Every kid playing shinny pretended to be Lafleur or Jean Béliveau, but Lemieux showed right away that he was more than just a pale imitation. His parents, Jean-Guy and Pierrette, made sure of that: family legend has it that they sometimes packed snow onto the living-room carpet to create an indoor surface on which Mario and his brothers could practise after dark. His first coaches marvelled at his poise and puck control. Throughout minor hockey he was able to manipulate the flow of the game, scoring at will. And like Gretzky, Lemieux seemed to have 360-degree vision on the ice - his passes were often more exciting than his goals.

Though otherwise reticent, Lemieux is not shy about his athletic talent. At 15, when he was drafted by the Laval Voisins of the Quebec Major Junior Hockey League, he boldly predicted that he would break the league scoring records. Sure enough, in the 1983-1984 season he tallied 282 points, obliterating the single-season record of 251 set by Pierre Larouche, who went on to star in the NHL with the Penguins and Canadiens. And on the final night of that season, needing three goals to tie Lafleur's record of 130, Lemieux scored six. While the NHL scouts drooled, the prodigy was cool. "I have always been very comfortable with what I do on the ice," he now says matter-of-factly. "I grew up doing it and it came pretty easily to me, so it's nothing special."

Lemieux is equally confident - some say arrogant - in off-ice matters. Both as a junior and as a professional, he has been widely criticized for declining invitations to play for Canada at world tournaments. And at the 1984 entry draft, after the Penguins selected him No. 1, Lemieux refused to honor the tradition of donning a jersey at the Pittsburgh table because the team had not yet signed him to a contract. Incidents such as those made Lemieux appear selfish and unpatriotic, a perception the aloof player did little to dispel. He felt he had good reasons - injuries, mostly - and that his actions were misunderstood.

He has also confounded his sponsors - which early in his career included Gillette, Micron Mega skates and Coca-Cola - by occasionally failing to show up at appointed times. "All that smiling-for-the-camera, shaking-hands stuff, that's not him at all," says Tocchet. Nowadays, Lemieux simply turns down most endorsement offers. Unlike Gretzky, who earns up to $8 million a year endorsing everything from soup to insurance, Lemieux lends his name mostly to hockey equipment manufacturers and trading cards. Still, he will not go hungry. With bonuses, he is scheduled to make $15 million next season, which will almost certainly enable him to overtake the still-unsigned Gretzky as the league's highest-paid player. "I just tell my agents that I'd rather not do much in the off-season," he says. "I know that is costing me a little bit of money, but I am lucky to make enough that I don't have to do those things."

When Lemieux does speak, people listen - which can be a problem. During the run-up to the Quebec referendum last summer, he told an inquiring reporter that the vote was of no concern to him because he lived in Pittsburgh. "Mario has done things his own way," says Marcel Dionne, the former Los Angeles Kings star. "He's the best player in the game, and he rates with the best players of all time, but he'll come out and say things that, in Montreal, would get you killed."

In fact, although he was the logical heir to the mantle worn by Aurel Joliat, Maurice Richard, Béliveau and Lafleur, Lemieux says he would never have survived had he been drafted by the Canadiens and played in the hockey hothouse that is Montreal. "I am such a private person that it would have been very difficult," Lemieux says. "All the media attention and fan pressure demand so much of your time, and I don't think I would have lasted too long in Montreal."

In Pittsburgh, Lemieux has found an unlikely but happy home. Steel City fans have embraced their reluctant hero, admiring his performance on the ice and honoring his desire for privacy off it. Although he is not much of a civic rah-rah type, he does host an annual golf tournament to benefit cancer research - "We collected nearly $100,000 last year," he says proudly. He lives in Sewickley, a leafy community 25 km west of Pittsburgh, with Nathalie and the kids: baby Austin joins daughters Lauren, 3, and Stephanie, 1. Lemieux indulges his passion for golf - he is very good at that, too - as a member at two local clubs, including storied Oakmont Country Club, site of several U.S. Opens. "Mario's idea of a perfect summer day," says Tocchet, "is to play golf with a few friends and then go home to his family for a quiet dinner."

Home life has not always been serene. Lemieux was scarred by a 1992 incident in a Bloomington, Minn., hotel when a friend, Dan Quinn, was accused of raping a young woman in Lemieux's hotel room. The charges were soon dropped, but the revelation that he and Quinn had women in the room while Nathalie was pregnant at home damaged Lemieux's public image, particularly in Quebec. His relationship with Nathalie survived. And Lemieux now credits her with helping him recover from his illnesses. "With the back infection, she was my nurse for three months," he says. "She learned how to do the intravenous and all that other stuff. She was there every day."

At work, certainly, Lemieux appears to be having more fun this season. His competitive fire is more evident, particularly against tougher opponents. In a home game against Eric Lindros and the Philadelphia Flyers, for instance, Lemieux made it clear that he was not about to cede any ground to his younger opponent. With mesmerizing puck control, Lemieux rang up three goals and two assists as the Penguins beat their cross-state rivals 7-4. And while he is still undemonstrative - Lemieux can make scoring a goal look about as much fun as going to the dentist - he took great pleasure in one of his goals, which he banked in off goalie Garth Snow from an impossible angle.

"The thing I like about Mario this year is the sparkle in his eye, the enjoyment of the game that I'd seen slipping when he got hurt," says Neale of Hockey Night in Canada. Lemieux agrees. "Every time you get away from something you love, it makes you appreciate it more," he says. "That's what I found out last season. I'm just glad to have the chance to come back to the game."

And the game is glad to have him - especially when he works his wizardry. In February, Lemieux produced what may have been the highlight of the 1995-1996 season. Bearing down on Canucks goalie Kirk McLean, he had the puck knocked off his stick by Martin Gelinas. But as it slipped behind him, Lemieux reached his stick back between his legs and astonishingly flipped a shot over McLean's shoulder into the far top corner of the net. No one could recall seeing anything like it. "He's so creative with the puck and something like that catches you off-guard," a stunned McLean told reporters afterward. "You don't mind being on a highlight film when it's a guy like him."

To cap his unlikely comeback, of course, Lemieux would like nothing more than to capture the Stanley Cup again. And he says he hopes to play in this summer's World Cup (the revamped Canada Cup). It was at the 1987 Canada Cup, where he teamed with Gretzky to score the series-winning goal against the Soviet Union, that Lemieux emerged as a leading force in the NHL. At the time, he seemed a good bet to break the Great One's single-season records for goals (92) and total points (215). But his health always got in the way. "What if he'd never been hurt, never been sick?" asks Dionne, the NHL's No. 3 all-time scorer. "People once said that Gretzky's records would not be broken but, I'll tell you, the Big Guy would have beaten them."

Despite the millions awaiting him next season, Lemieux says he will not play only for his paycheque. "If my back's OK, if I'm healthy, I'll play," he says. "But I'll see how it goes this summer." Cancer taught him that he cannot take anything for granted, even in this extraordinary season. In December, he found a lump on his neck near where his Hodgkin's had first appeared. "It can be alarming, especially with what I had gone through before," he now says. "But I kept an eye on it, showed it to the doctors, and did all the tests - CT scans, MRIs and so on. There was nothing serious."

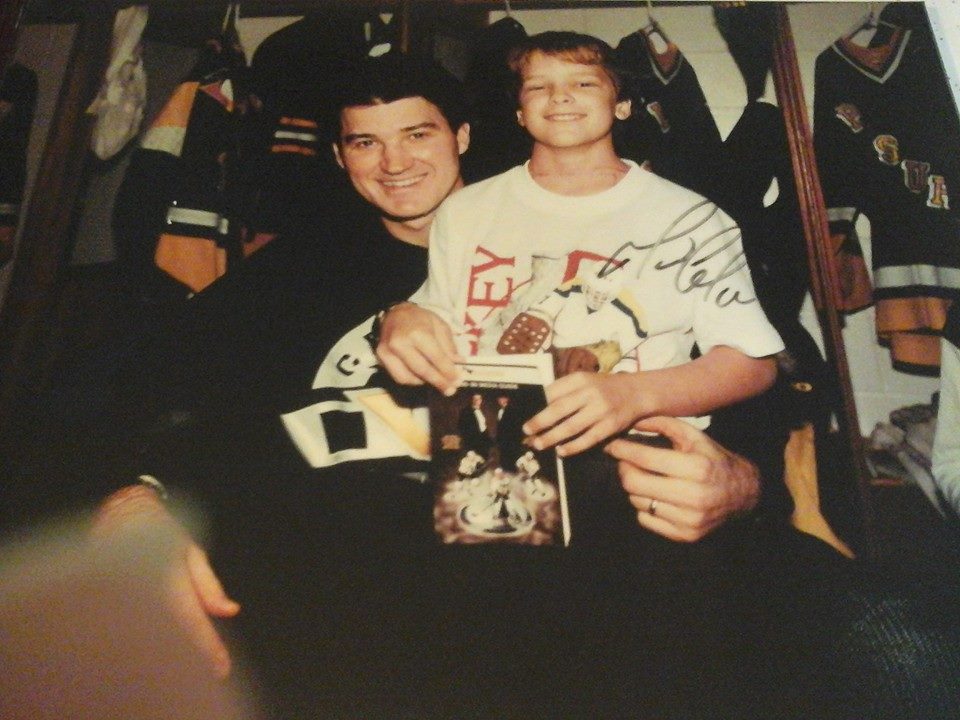

Without fanfare, Lemieux takes time to cheer up fellow cancer sufferers, especially kids. David Boulet, who went to the practice in St. Petersburg hoping for an autograph, got a lot more. Lemieux gave him a signed stick, set aside four tickets so that the Boulet family could attend that night's game, and then invited the youngster into the Penguins' dressing-room. Boulet waded through the sweaty, post-practice debris, gathering signatures and getting his hair mussed by the players, and then climbed up on the bench beside where Lemieux sat in a towel.

"He would have been happy just to meet Mario, someone who had survived the cancer," said Boulet's father, Pierre, a native of Magog, Que., who moved to Florida seven years ago. "This means so much." The hockey star, of course, played down his efforts, saying he knew how scared the little boy was, because he had been scared, too. Not that Lemieux showed it, of course. That's not his style.

Maclean's April 8, 1996

Share on Facebook

Share on Facebook Share on X

Share on X Share by Email

Share by Email Share on Google Classroom

Share on Google Classroom