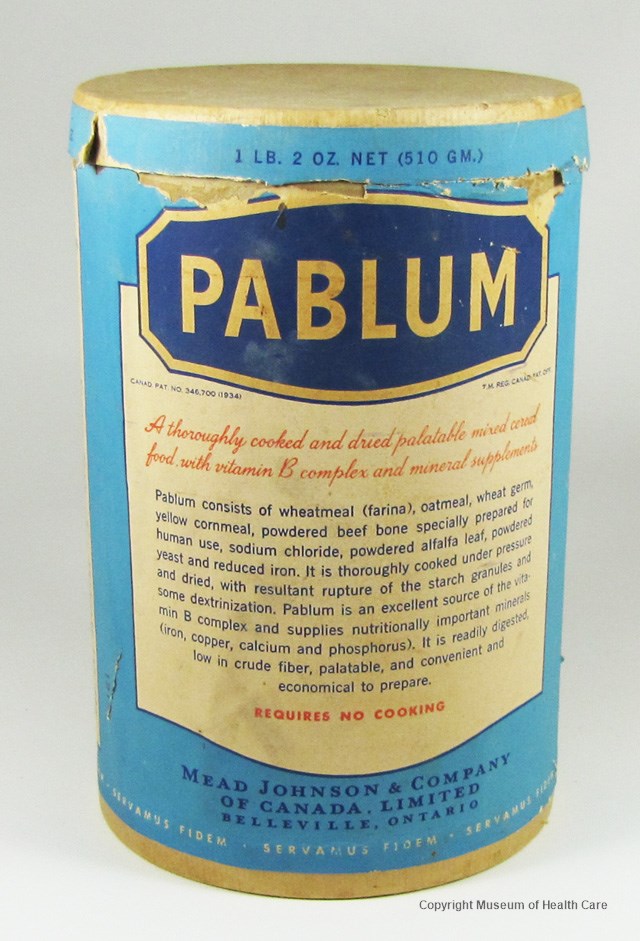

Pablum is a multi-grain processed cereal developed as a nutritious, precooked digestible food for infants. The cereal was first developed at the Hospital for Sick Children in Toronto in 1930 by pediatric doctors Theodore Drake and Frederick Tisdall under the supervision of physician-in-chief Alan Brown. Pablum became commercially available in 1934 through an agreement with the Mead Johnson & Company and was used as a brand name through the early 21st century.

Infant Mortality and Malnutrition

From the 1920s and into the 1940s, Canada recorded high rates of infant mortality. (See also Childbirth in Canada; Death and Dying.) Malnutrition was a leading cause of infant mortality along with diseases caused by contaminated and unpasteurized cows’ milk. (See also Dairy Industry.) During the early 20th century, many mothers produced homemade formulas or cereals to supplement an infant’s diet. These formulas, often made in the form of soaked biscuits, lacked the vitamins and minerals required to prevent childhood illnesses such as rickets, a disease that softened children’s bones. As the digestive tracts of infants were still in the developmental stage, feeding them grain-heavy cereals that sat out unrefrigerated for days accumulating bacteria often led to diarrhea and other gastrointestinal issues.

Research and Development

In 1918, the Nutritional Research Laboratories (NRL) at the Hospital for Sick Children was opened. (See also Dietetics.) Dr. Alan Brown, the hospital’s physician-in-chief, recruited Dr. Fred Tisdall and Dr. Theodore Drake as nutrition researchers. In 1929, Dr. Tisdall was appointed director of the NRL. Under his guidance the NRL investigated the development of nutritious food for children via research into irradiated foods and products that delivered vitamins. The first successful product Tisdall and Drake worked on was a biscuit for children described in a January 1930 presentation as “a new whole wheat irradiated biscuit, containing vitamins and mineral elements.” An agreement was made with the London, Ontario, based McCormick Manufacturing Company to produce the biscuits commercially, which were introduced to the public that year as McCormick’s Sunwheat Biscuits. The hospital established the Paediatric Research Foundation to handle royalties from the biscuits and other future commercial products developed from the NRL’s research. (See also Pediatrics.)

While Sunwheat Biscuits were ideal for children, they were not suitable for infants. Tisdall and Drake worked to solve this problem by developing a cereal that was rich in minerals, protein and vitamins, retained whole grains without causing constipation or other digestive problems, and that could easily be spoon-fed to infants. Ingredients used included whole wheat meal, oatmeal, corn meal, wheat germ, bone meal, brewer’s yeast, alfalfa and salt (see also Wheat; Cereal Crops). The recipe was fortified with calcium phosphorus, iron, copper and five vitamins. Initial formulations still required long cooking times, and initial taste tests among hospital staff and families of the researchers led to complaints the cereal was too bland.

When the research team learned of a new process to dehydrate milk using a heated drum, they experimented with similar techniques to produce the new cereal. The formula was cooked in giant pressurized steam kettles, dried on a heated rotating drum, then scraped off. The resulting cereal was a dry, flaky powder that retained the desired nutrients. Busy mothers could quickly mix the cereal, which kept indefinitely, with milk or water. The new cereal was dubbed “Pablum” after pabulum, the Latin word for food.

Patent and Sale

The Hospital for Sick Children approached Mead Johnson & Company to market Pablum. A patent was taken out in Tisdall’s name on behalf of the Paediatric Research Foundation. As with Sunwheat Biscuits, SickKids received a royalty for every container of Pablum sold for the next quarter century. Writer Max Braithwaite later noted in his 1974 publication, Sick Kids: The Story of The Hospital for Sick Children in Toronto, that “it turned out to be an excellent deal for many years.” By 1978, it was estimated that Pablum had earned the hospital $7 million in royalties. This money was used to support further research into enriched foods, which, by the end the Second World War, led to many foods being enriched with vitamins.

To give Pablum an air of scientific legitimacy, it was initially sold only through drug stores when it was introduced to the public in 1934. Mead Johnson also advertised the cereal in medical and nursing journals.

Controversy

While Dr. Alan Brown has been credited with co-inventing Pablum, his role has been disputed. Often listed with Tisdall and Drake among the product’s discoverers, his position as physician-in-chief at the Hospital for Sick Children entitled him to be credited with all books and papers originating from the institution. It is likely that Brown did not directly participate in the lab work, but provided the support required to carry it out.

Dr. Frederick Tisdall’s reputation was later tarnished through his involvement in experiments conducted on Indigenous children during the 1940s (see Indigenous Peoples in Canada). These experiments compared the nutritional implications of fortified foods by further malnourishing subjects who were already near starvation. (See also Residential Schools in Canada.) At the time of these experiments, Tisdall was a chief scientific officer with the federal Department of Nutrition.

Dr. Theodore Drake’s widow reputedly ate Pablum as her daily breakfast until she discovered in 1974 that the manufacturer had added taste-enhancers like salt, sugar and vegetable oil. (See also Sugar Industry; Vegetable Oil Industry.) “Ironically,” the Globe and Mail noted years later in a 1996 article, “the originators had deliberately not added sweeteners for fear that a baby would develop a sweet tooth, obesity and tooth decay.”

Legacy

By 1951, four additional formulations of Pablum were commercially available, partly to fight the perception that for all of its nutritional value the brand itself had become a synonym for blandness. Print advertisements from Chatelaine Magazine in the early 1960s declared that “from every dish of Pablum, there wafts a gentle, special Pablum aroma” and that “to a wee one, it hints of the baby-delicate flavour to come.”

The rights to the Pablum brand name were acquired from Mead Johnson by H.J. Heinz in 1995. While the copyright was renewed in 2016 to reflect a subsequent corporate merger, the branding ceased to be used commercially during the early 21st century. Pablum was commemorated with a postage stamp issued by Canada Post in March 2000 as part of its “Millennium” series. The stamp depicted a 15-month-old girl with the cereal smeared all over her mouth.

Share on Facebook

Share on Facebook Share on X

Share on X Share by Email

Share by Email Share on Google Classroom

Share on Google Classroom