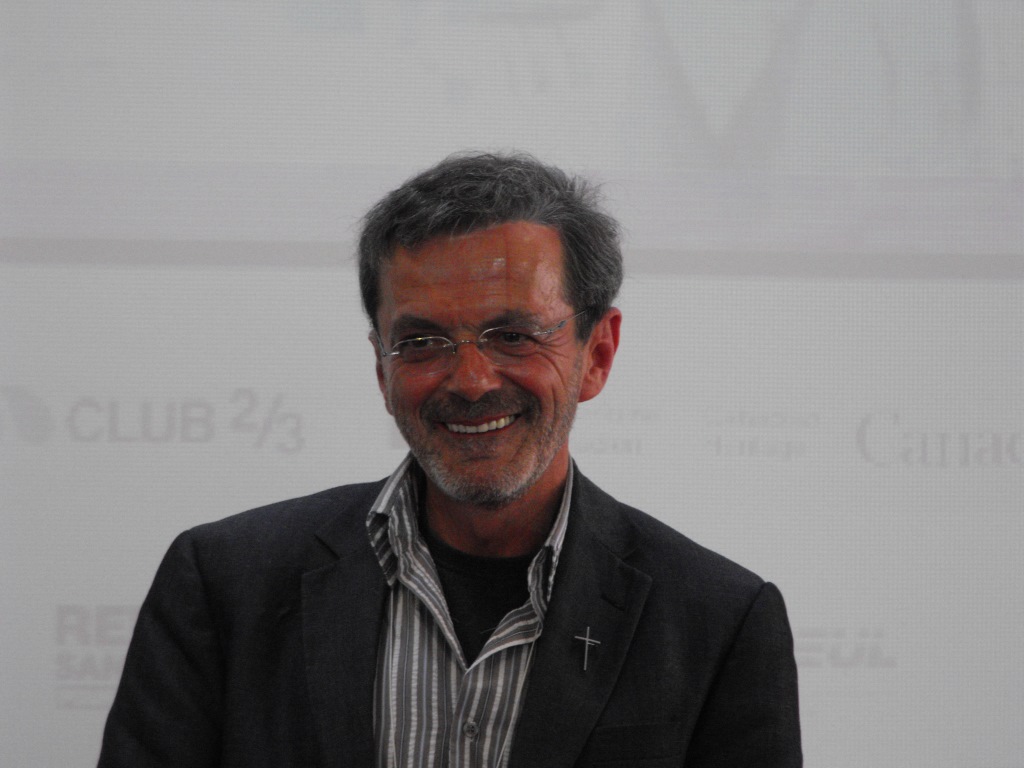

Troubled childhood and adolescence

Raymond Gravel was the fourth child in a family of four boys and two girls. His parents, Yvon Gravel and Réjeanne Mondor, owned a dairy farm in the municipality of Saint-Gabriel, in the township of Brandon, QC. Raymond was his mother’s favourite son, but he had a conflictual relationship with his father, who was physically violent with him. A brilliant, hard-working student nonetheless, Raymond attended secondary school at the École Sacré-Cœur in Saint-Gabriel-de-Brandon, QC, where the teaching was supervised by Catholic brothers.

Under the influence of unsavory friends, he experimented with several types of drugs. At age 16, he left the family home and went to live with Roméo and Simone Allard, a childless couple who owned a hotel where he did odd jobs in exchange for lodging and where he seems to have found some peace of mind.

In 1971, he began attending the École Thérèse-Martin in Joliette, QC, where he completed his secondary studies. In September 1972, he entered the labour market. He worked first as a clerk at the National Bank of Canada in Sorel, QC, then as a teller at a Bank of Montreal branch on Montréal Island.

The night life of the big city afforded him great freedom and many distractions. He developed a dependence on drugs and worked for a while as a male escort. But he found that prostitution did not suit him as a lifestyle and soon gave it up.

In 1977, Gravel began to think about his future. In his diary, he wrote, “I can’t take it anymore. I need help. I can’t seem to find my way back.” After a short stay at the Trappist monastery in Oka, QC, he decided to become a priest. He then completed his college studies at the Cégep Marie-Victorin and the Cégep du Vieux-Montréal, entered the Faculty of Theology at Université de Montréal in September 1979 and received his bachelor’s degree from that institution on 17 February 1982, at the age of 29.

Path to the priesthood

As a candidate for the priesthood, Gravel worked in several Catholic parishes and schools in Québec’s Lanaudière region. Aurélien Breault, a parish priest in the community of Saint-Henri de Mascouche, became his mentor and spiritual father. The young candidate was already concerned about many issues that were controversial among Catholics, including priestly celibacy and Church acceptance of divorced people who had remarried.

Gravel’s path to the priesthood was long and arduous, and he sometimes questioned his vocation. To ease his impatience, he pursued more education and earned a master’s degree in pastoral studies from Université de Montréal in 1984. He was ordained a deacon on 23 February 1986 and a priest on 29 June of the same year, in the church of his native village of Saint-Damien, QC. The ceremony was attended by 500 guests, including 90 priests and the members of his family. Raymond Gravel was 33 years old, and he considered this the best day of his life. During the ceremony, he knelt before his father and asked for his blessing. Touched by the gesture, Yvon Gravel placed his hand on his son’s head and bowed to him in turn. Thus the father and son were reconciled after all those years.

A priest with modern ideas

Fr. Gravel then began to devote himself to his priestly mission. He provided end-of-life support to numerous AIDS patients and became a chaplain for the Cursillos (a lay Catholic organization), the scouting movement, the fire departments of Berthierville and Mascouche, QC, and the police department of Laval, QC. He published articles in diocesan magazines and officiated at weddings, baptisms and funerals.

In 1991, Gravel left for Italy to pursue a second master’s degree, this time in Biblical studies. His proposed research topic was the conception of Jesus or the virginity of his mother, Mary. In Rome, the Jesuits took a dim view of this idea and suggested that he go back to finish his studies in Montréal. On returning to Québec, Fr. Gravel wrote his thesis under the supervision of Professor André Myre of Université de Montréal and received his degree in June 1992.

Although religion had become less of a force in Québec life since the Quiet Revolution, Fr. Gravel still took strong stances on many contemporary social issues and questioned certain positions of the Catholic Church, such as its ban on same-sex marriage (see Lesbian, Gay, Bisexual and Transgender Rights in Canada) and its opposition to abortion and to medically assisted death (see Medical Ethics).

With his forthright manner, Fr. Gravel had no trouble in attracting media coverage — for example, in 2007, when he defended the Christian values of Québec society during the public controversy over reasonable accommodation on cultural and religious grounds.

Political career

As Bloc Québécois Member of Parliament for the riding of Repentigny from 2006 to 2008, Fr. Gravel was the first priest from Québec to sit in the House of Commons. While serving in Parliament, he voted against the controversial Bill C-484, which would have recognized unborn fetuses as crime victims independent of their mothers. He also expressed his support for Dr. Henry Morgentaler when the Canadian cardinals opposed his nomination for the Order of Canada. This position earned Gravel the animosity of his colleagues and the pro-life movement, which demanded that he be suspended from the priesthood under canon law. In 2011, Fr. Gravel launched lawsuits for libel and defamation of character against a pro-life association and an anti-abortion website. One of these cases was settled out of court in 2013. The other continued until it was dropped following Fr. Gravel’s death in 2014.

Disappointed by his experience of political life and strongly encouraged by the Vatican to choose between politics and the Church, Fr. Gravel decided not to run in the federal general election of October 2008. But he remained faithful to the cause of Québec sovereignty (see Separatism) and proudly wore his blue stole, with its embroidered cross and fleur-de-lys, every time he celebrated mass on Saint-Jean-Baptiste Day.

Honours

In 2004, Raymond Gravel received the Fondation Émergence Fight Against Homophobia Award (known since 2014 as the Laurent McCutcheon Award) for the message of hope that he gave by championing inclusion and acceptance of homosexuals. Shortly before his death, he was also honoured by the City of Mascouche, which named a fire hall after him.

In August 2013, Fr. Gravel learned that he had lung cancer. The cancer spread, and on 11 August 2014, he died in the Lanaudière regional hospital at age 61. He lay in state in the cathedral of Joliette and was laid to rest in the city’s Saint-Pierre cemetery.

In August 2015, a documentary film about his life — Raymond Gravel, un sacré curé!, directed by Patrick Brunette — was shown on the Télé-Québec public television network.

Share on Facebook

Share on Facebook Share on X

Share on X Share by Email

Share by Email Share on Google Classroom

Share on Google Classroom