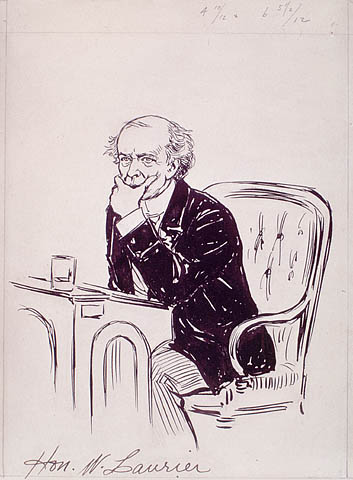

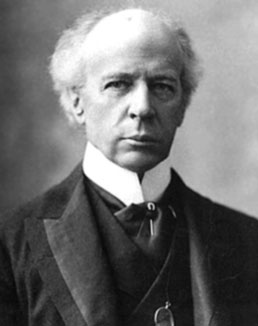

He remains arguably the finest public speaker ever to serve as Canadian prime minister . Urbane, wily and silver-tongued, Wilfrid Laurier was a master at inspiring people with spoken words. Perhaps it was easier in his time — before Twitter and TV soundbites and micro attention spans — when public speaking was the best way to reach voters, and when speeches in Parliament actually mattered. Among his gifts to Canada, Laurier’s words — among them the “sunny ways” resurrected by Justin Trudeau — are his great legacy. This month (20 November to be exact), we celebrate what would have been Laurier’s 175th birthday by remembering him through his oratory.

1871: Confederation

As a young lawyer, Laurier deeply opposed the idea of Confederation. Like the Parti rouge members he associated with in Canada East (formerly Lower Canada), he once described any union of the British North American colonies as “the tomb of the French race and the ruin of Lower Canada."

After 1867, however, Laurier accepted Confederation, and would spend the rest of his life passionately praising his new country — and the legal protections of its Constitution — for allowing French and English to live and thrive peacefully side by side in a single state. On 10 November 1871, as a newly elected member of the Québec provincial legislature, he articulated his freshly acquired admiration for Canada by speaking on what would become his favourite subject.

… the fact is one of which we can be justly proud, that so many different races and so many opposite creeds should find themselves concentrated on this little corner of earth and that our constitution should prove broad enough to leave them all plenty of elbow room, without friction or danger of collision and with the fullest latitude to each to speak its own tongue, practise its own religion, retain its own customs and enjoy its equal share of liberty and of the light of the sun.

1874: Louis Riel

The 1869 Métis uprising in Red River had deeply divided Canadians along religious and linguistic lines. Five years later, the election of Louis Riel as a Member of Parliament (MP) prompted a debate about whether the House of Commons should allow Riel to take up his seat there.

Wilfrid Laurier — by this time a federal MP in the new Liberal government of Alexander Mackenzie — stood firmly on Riel’s side. Laurier had little personal sympathy for Riel. Politically, however, he used Riel and the Métis cause as a way of staking out the moderation and pragmatism that would become a hallmark his career. On 15 April 1874, he issued this stirring defence of Riel in the House of Commons.

It has also been said that Mr. Riel was only a rebel. How was it possible to use such language? What act of rebellion did he commit? Did he ever raise any other standard than the national flag? Did he ever proclaim any other authority than the sovereign authority of the Queen? No, never. His whole crime and the crime of his friends was that they wanted to be treated like British subjects and not to be bartered away like common cattle. If that be an act of rebellion, where is the one amongst us who, if he had happened to have been with them, would not have been rebels as they were?

1877: Political Liberalism

By 1877, Laurier was a rising political star in Québec, although his profile outside his native province was not yet established. On 26 June 1877, Laurier spoke to members of Le Club Canadien in Québec City on the risky topic of liberalism — deemed a radical threat at the time to Québec’s conservative elites and to the Roman Catholic Church.

Laurier disarmed such fears by stating clearly what Liberals held dear: political freedom, respect for the Crown, the continuance of Canada’s democratic institutions and religious tolerance. The speech was a master stroke. Overnight, Laurier created space in Québec for the Liberal Party and became, for the first time, a national figure.

I know that for a great many of my fellow citizens, the Liberal Party is a party composed of men holding perverse doctrines, with and dangerous tendencies, and knowingly and deliberately progressing towards revolution… a new form of evil, in other words, a heresy.… If to be a Liberal is a term of reproach, that reproach I accept. If it is a crime to be a Liberal, then I am guilty. One thing only I claim, that is that we be judged according to our principles.

1886: The Mighty St. Lawrence

By 1886, Louis Riel had been executed, again dividing French- and English-speaking Canadians. Laurier had continued to defend Riel, condemning the Conservative government’s use of violence to suppress the North-West Resistance, and pleading with anglophone Canadians to accommodate the political concerns of francophone minorities. Speaking in Toronto on 10 December 1886, he defended French Canadian identity, and painted an evocative vision of Canada, using the St. Lawrence River as a metaphor for the country.

I will say this, that we are Canadians. Below the island of Montréal the water that comes from the north from Ottawa unites with the waters that come from the western lakes. But uniting, they do not mix. There they run parallel, separate, distinguishable, and yet are one stream, flowing within the same banks, the mighty St. Lawrence, and rolling on toward the sea bearing the commerce of a nation upon its bosom — a perfect image of our nation. We may not assimilate, we may not blend, but for all that we are the component parts of the same country.

1891: Macdonald Eulogy

On 8 June 1891, Laurier rose in the House of Commons to eulogize his political adversary, Sir John A. Macdonald, who had died just two days before. Laurier delivered with his usual eloquence, gesturing broadly at the legacy the “Old Chieftain” had left behind. “The life of Sir John Macdonald…is the history of Canada,” said Laurier. Macdonald, he said, was associated with all the political moves that had brought “two small provinces…united by a bond of paper, and united by nothing else” into nationhood.

But Laurier was sharpest in his assessment of Macdonald’s leadership. After all, Laurier had observed his opponent from across the floor for the last 17 years, and studied his career for even longer. He saw how Macdonald helped forge Confederation, how he built cabinets, filled Senate seats and wielded power over caucus. Laurier had even been outfoxed by the veteran politician in a recent federal election, witnessing Macdonald at his most cunning.

After Macdonald died, a series of Conservative prime ministers followed in quick succession. None could fill the gap left by Macdonald. Laurier would eventually become as great a national figure as Sir John A, but that wasn’t at all clear at the time of Macdonald’s death. This speech, however, gave hints of it.

The fact that [Macdonald] could congregate together elements the most heterogeneous and blend them into one compact party, and to the end of his life keep them steadily under his hand, is perhaps altogether unprecedented. The fact that during all those years he retained unimpaired not only the confidence, but the devotion — the ardent devotion and affection of his party, is evidence that beside those higher qualities of statesmanship to which we were the daily witnesses, he was also endowed with those inner, subtle, indefinable graces of soul which win and keep the hearts of men.

1895: The Sunny Way

The Manitoba Schools Question involved a struggle over the rights of francophones in Manitoba to receive an education in their mother tongue and their religion, constitutional rights that had been revoked by the provincial government of Thomas Greenway in 1890.

Laurier’s solution to the problem followed what he called the “sunny way” — the way of negotiation, diplomacy and compromise — rather than forced legislation. He first used the term 8 October 1895, when he was leader of the opposition, in a speech he delivered in Ontario. The sunny way is a reference to one of Aesop’s Fables, in which the wind and the sun compete to see who can motivate a man to remove his jacket. The sun shines down, pleasantly and patiently, and the wind blows with bluster. The sun ultimately wins the day, proving that patience and enticement are more effective than force and coercion.

After coming to power in 1896, Laurier settled the Manitoba Schools Question with sunny ways — but the politically expedient settlement his government achieved came at a steep price: the sacrificing of French language minority rights in Manitoba.

The government are very windy. They have blown and raged and threatened, but the more they have threatened and raged and blown the more that man Greenway has stuck to his coat.… If it were in my power… I would try the sunny way. I would approach this man Greenway with the sunny ways of patriotism, asking him to be generous to the minority, in order that we may have peace amongst all the creeds and races which it has pleased God to bring upon this corner of our common country. Do you not believe that there is more to be gained by appealing to the heart and soul of men rather than to compel them to do a thing?

1904: Canada’s Century

The 19th century has been the century of United States’ development… Let me tell you, my fellow countrymen, that all the signs point this way, that the 20th century shall be the century of Canada and of Canadian development. For the next 70 years, nay for the next 100 years, Canada shall be the star towards which all men who love progress and freedom shall come.

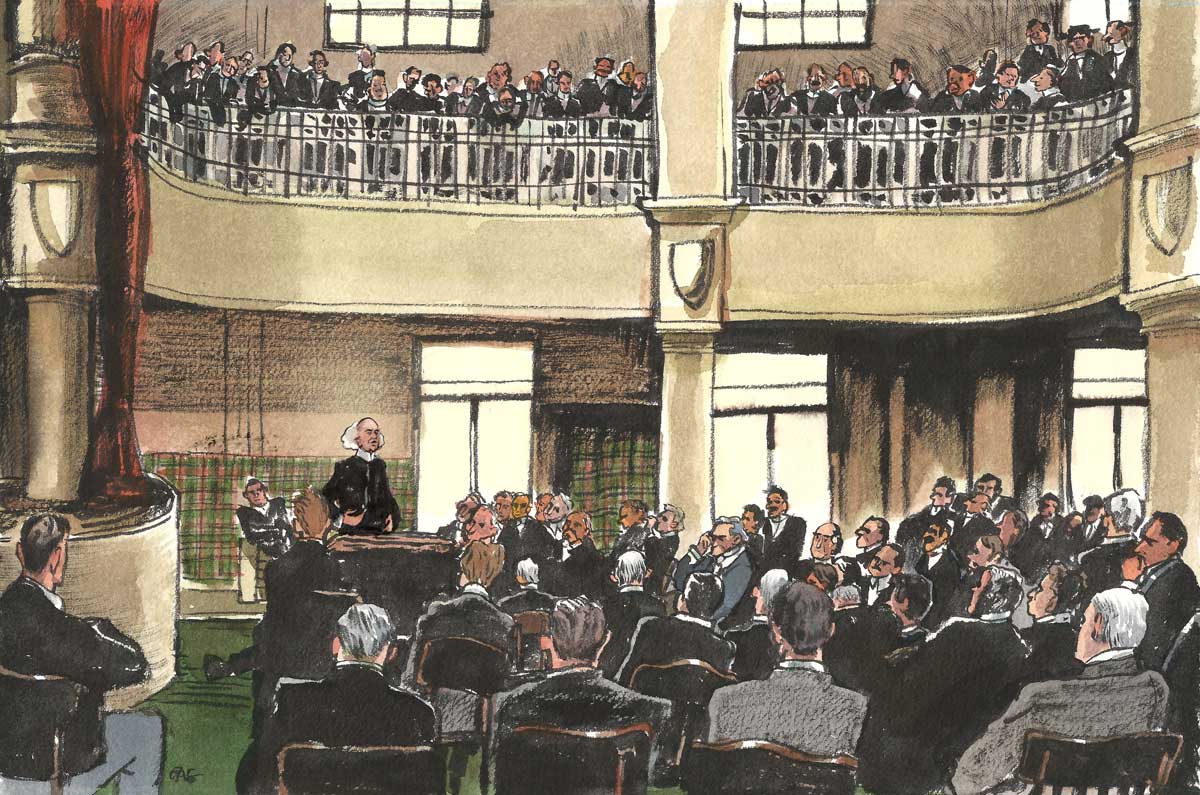

Remembered for his liberal ideals, Laurier was also a skilled political manipulator. He used his oratory on the campaign trail, both to savage his opponents, and to shamelessly pluck the heartstrings of Canadian voters. He did both in this speech delivered while campaigning in Toronto on 14 October 1904 at Massey Hall. He first defends his eight-year record in power by comparing his government’s “minute” and “trivial” mistakes with the “mountain of iniquity” that the Tories built while in power for some 24 years. He then sounds the trumpet of patriotism, uttering a version of his most famous line (delivered in different ways, in several speeches that year) that the 20th century would belong to Canada.

1905: Let Them Become Canadians

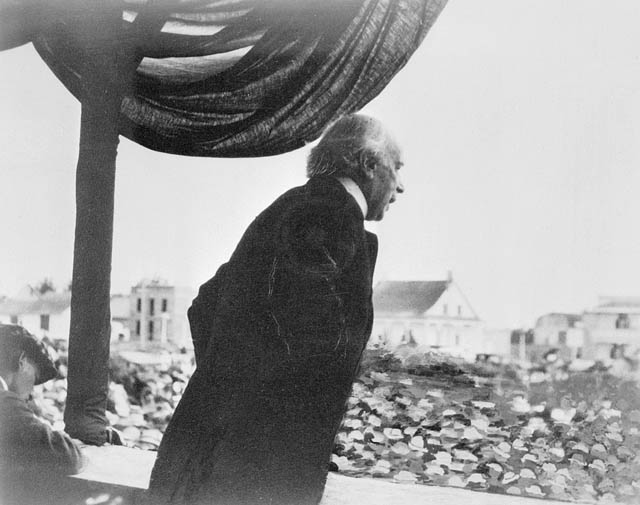

On 1 September 1905, Laurier spoke before an audience of some 10,000 people in Edmonton, the newly minted capital of Alberta, which had just joined Confederation along with Saskatchewan. It had been 11 years since he’d last visited Edmonton, and he remarked that so much had changed in that time. He noted the growth of cities in the West, as well as the development of industry and transportation, agriculture and trade there. “Gigantic strides are made on all sides over these new provinces,” he said.

It was a crowning moment of a movement — to colonize the West — and Laurier was there to thank the immigrants and settlers who had made that possible. Though the Laurier government’s immigration policies championed the arrival of some and barred the landing of others, his comments on acceptance in this speech served as a better model to follow.

We want to share with them our lands, our laws, our civilization. Let them be British subjects, let them take their share in the life of this country, whether it be municipal, provincial or national. Let them be electors as well as citizens. We do not want nor wish that any individual should forget the land of his origin. Let them look to the past, but let them still more look to the future. Let them look to the land of their ancestors, but let them look also to the land of their children. Let them become Canadians… and give their heart, their soul, their energy and all their power to Canada.

1916: Faith Is Better than Doubt and Love Is Better than Hate

As the country’s first francophone prime minister, Laurier worked tirelessly to strengthen and unify the fledgling country and build bridges between its French and English citizens — in spite of the ill will this often brought from his fellow Québécois. Unity and fraternity were ideals that governed his life, as he told a group of young Canadians on 11 October 1916 (sentiments borrowed by Jack Layton at the end of his life).

I shall remind you that already many problems rise before you: problems of race division, problems of creed difference, problems of economic conflict, problems of national duty and national aspiration. Let me tell you that for the solution of these problems you have a safe guide, an unfailing light, if you remember that faith is better than doubt and love is better than hate. Banish hate and doubt from your life. Let your souls be ever open to the strong promptings of faith and the gentle influence of brotherly love. Be adamant against the haughty, be gentle and kind to the weak. Let your aim and your purpose, in good report or in ill, in victory or in defeat, be so to live, so to strive, so to serve as to do your part to raise the standard of life to higher and better spheres.

Pillar of Fire

I am branded in Québec as a traitor to the French, and in Ontario as a traitor to the English. In Québec, I am branded as a jingo, and in Ontario as a separatist. In Québec, I am attacked as an Imperialist, and in Ontario as an anti-Imperialist. I am neither. I am a Canadian. Canada has been the inspiration of my life. I have had before me as a pillar of fire by night and a pillar of cloud by day a policy of true Canadianism, of moderation, of conciliation.

Share on Facebook

Share on Facebook Share on X

Share on X Share by Email

Share by Email Share on Google Classroom

Share on Google Classroom