Halifax was devastated on 6 December 1917 when two ships collided in the city's harbour, one of them a munitions ship loaded with explosives bound for the battlefields of the First World War. What followed was one of the largest human-made explosions prior to the detonation of the first atomic bombs in 1945. The north end of Halifax was wiped out by the blast and subsequent tsunami. Nearly 2,000 people died, another 9,000 were maimed or blinded, and more than 25,000 were left without adequate shelter.

This is the full-length entry about the Halifax Explosion. For a plain-language summary, please see Halifax Explosion (Plain-Language Summary).

Wartime City

Halifax was a busy, wartime port city in 1917. The First World War had been underway for three years, exposing Canadian servicemen to injury, death and hardship, but bringing prosperity to Halifax. After decades of hard economic times, the city was a hub of Canada's war effort. With one of the finest and deepest ice-free harbours in North America, Halifax was the port through which tens of thousands of Canadian, British Empire and American troops passed on their way to the battlefields of Europe, or on their way home.

The city’s population of nearly 50,000 was swollen by the influx of troops, and by Canadian and British naval officials supervising activity in the port. Millions of tonnes of supplies also passed through the port, en route to the war — wheat, lumber, coal, food, munitions and armaments — arriving by rail and departing on ships. The harbour was not only home to Canada's fledgling Royal Canadian Navy, but was also a base for Royal Navy vessels and merchant ships from around the world, needing repair or resupply.

All this activity boosted the economy, made jobs plentiful, and gave the small city a buzz its residents had not experienced in decades. Civilian migrants arrived in search of available work — at the dockyards, railyards, the sugar refinery and other factories. Women also took up paid jobs once filled by men, who were now away at war. Soldiers and sailors filled the streets. Despite the war's horrors in Europe, it created wealth and opportunity for many in Halifax. It also boosted demand for bootleg liquor and prostitution — upsetting the Victorian-era morals and sensibilities many Haligonians still harbored.

Much of Halifax's industrial activity was centred in the working-class neighbourhood of Richmond, in Halifax's north end — a tightly knit community of wooden homes, schools and churches. Unpaved streets criss-crossed the slopes of Richmond, leading down to the harbour where factories, naval piers, a sprawling dry dock and railway yards bustled with activity. Further north of Richmond was the Black community of Africville. Across the harbour, on the more sparsely populated Dartmouth shore, was the long-time Mi'kmaq village of Turtle Grove.

Imo and Mont-Blanc

The Mi'kmaq called the harbour K’jipuktuk, or Chebucto, meaning "great harbour." During the war, the harbour was protected by a network of fortified gun emplacements and observation posts, manned by military personnel. Many Halifax residents believed that German battleships might one day arrive offshore and shell the city. Underwater nets, to guard against German submarines, were also strung across the harbour entrance. Gates in the nets were opened periodically during the day, allowing surface traffic to come and go.

At the harbour's innermost reaches, the vast, sheltered expanse of Bedford Basin made Halifax an important staging area for transatlantic, naval-escorted convoys — organized as protection against marauding submarines at sea. Convoys of merchant ships assembled in Bedford Basin before ferrying their supplies and soldiers to the war effort in Europe.

In early December, one of the merchant ships in port was the large, Norwegian vessel Imo, en route from Halifax to New York to pick up relief supplies for the beleaguered population of war-torn Belgium. The words "BELGIAN RELIEF" were emblazoned in large block letters on the Imo's side. Another was the French munitions ship Mont-Blanc — filled with tons of benzol, the high explosive picric acid, TNT and gun cotton — arriving in Halifax to join a convoy across the ocean. Before the war, the port of Halifax was under civilian control, and ships carrying munitions or explosives were not allowed into the inner reaches of the harbour. However, the British Admiralty had assumed command of the port in wartime, and ships such as Mont-Blanc were now permitted through the harbour and into Bedford Basin.

Collision

The Imo was departing the harbour on the morning of 6 December 1917. It had emerged from Bedford Basin and was travelling south through the Narrows — the harbour's tightest navigation section — moving on the eastern, Dartmouth side of the channel instead of the Halifax side to the west, where outgoing vessels normally travelled. Imo's path required incoming ships to pass to its right or starboard side, rather than to its left or port side, which was customary. Imo had an experienced, local harbour pilot on board, William Hayes, who knew the navigation rules of the harbour. However, earlier encounters that morning with two inbound vessels moving towards Bedford Basin — both of which Imo had passed starboard-to-starboard — resulted in the unusual position that Imo now occupied, too far to the east, on the wrong side of the Narrows.

The Mont-Blanc had arrived outside Halifax the previous day and anchored overnight at the mouth of the harbour. On the morning of 6 December, the ship was cleared by harbour authorities to proceed toward Bedford Basin. Despite the Mont-Blanc's dangerous cargo, there was no special protocol for the passage of munitions ships in the harbour. Other ships such as the Imo were not ordered to hold their positions that morning until the Mont-Blanc had made safe passage through the port.

Francis Mackey, Mont-Blanc's pilot, was guiding the ship inbound on the Dartmouth-side of the Narrows, when he encountered the Imo heading straight towards him in what he believed was Mont-Blanc's lane. Mackey would later maintain that the Imo was moving at an unsafe speed for such a large, unwieldly ship in the harbour, and also that incoming ships (in this case Mont-Blanc) had the right-of-way over outgoing vessels. Regardless of the accuracy of those claims, what is certain is that the Imo was sailing too far to the east, in what should have been Mont-Blanc's path.

After a series of whistles and miscommunications between the officers and pilots on the two ships, and failed manoeuvres to avoid a collision, the Imo struck the starboard bow of the Mont-Blanc. After a few moments the two ships parted, leaving a gash in Mont-Blanc's hull and generating sparks that ignited volatile grains of dry picric acid, stored below its decks.

For nearly 20 minutes the Mont-Blanc burned. The fire encompassed burning drums of benzol, a form of gasoline, on the ship's top deck, sending a huge plume of black smoke into the sky. The spectacle attracted the attention of people on shore, including children on their way to school, and drew many residents to their windows and others towards the ship itself. In the harbour, teams of firefighters and sailors from other ships headed toward Mont-Blanc,hoping to put out its fire.

Few understood the danger, except for a handful of harbour and naval officials, as well as Francis Mackey and the French-speaking crew of the Mont-Blanc, who fled the ship after the fire broke out, rowing desperately in lifeboats for the Dartmouth-side of the harbour. As they did so, the crippled and burning Mont-Blanc drifted toward Pier 6 on the Halifax shore — a busy area filled with residential homes, businesses, moored ships, the Royal Naval College of Canada, and a large sugar refinery.

Vincent Coleman

At the nearby railway yards, two men learned of the ship’s contents and the danger of explosion. Chief clerk William Lovett told people in the yards about the Mont-Blanc's deadly cargo and called an agent further up the line to warn him of the danger.

Vincent Coleman, a railway dispatcher, controlled the busy freight- and passenger-rail traffic coming and going from the Halifax peninsula. He was about to flee his office when he realized that trains were due to arrive — including the 8:55 a.m. train from Saint John, New Brunswick, with hundreds of passengers on board. As the Mont-Blanc burned and the minutes ticked by, Coleman stayed at his post, tapping out a message on his telegraph key, warning stations up the line to stop any trains from entering Halifax. "Munitions ship on fire. Making for Pier 6. Goodbye." Coleman and Lovett were both killed in the explosion.

The Saint John train was ultimately saved, not because of Coleman's message, but because it was running late and never reached the north end of the city. However, Coleman's message, sent in the final minutes of his life, was among the earliest alerts received by the outside world about the disaster in Halifax.

Explosion and Tsunami

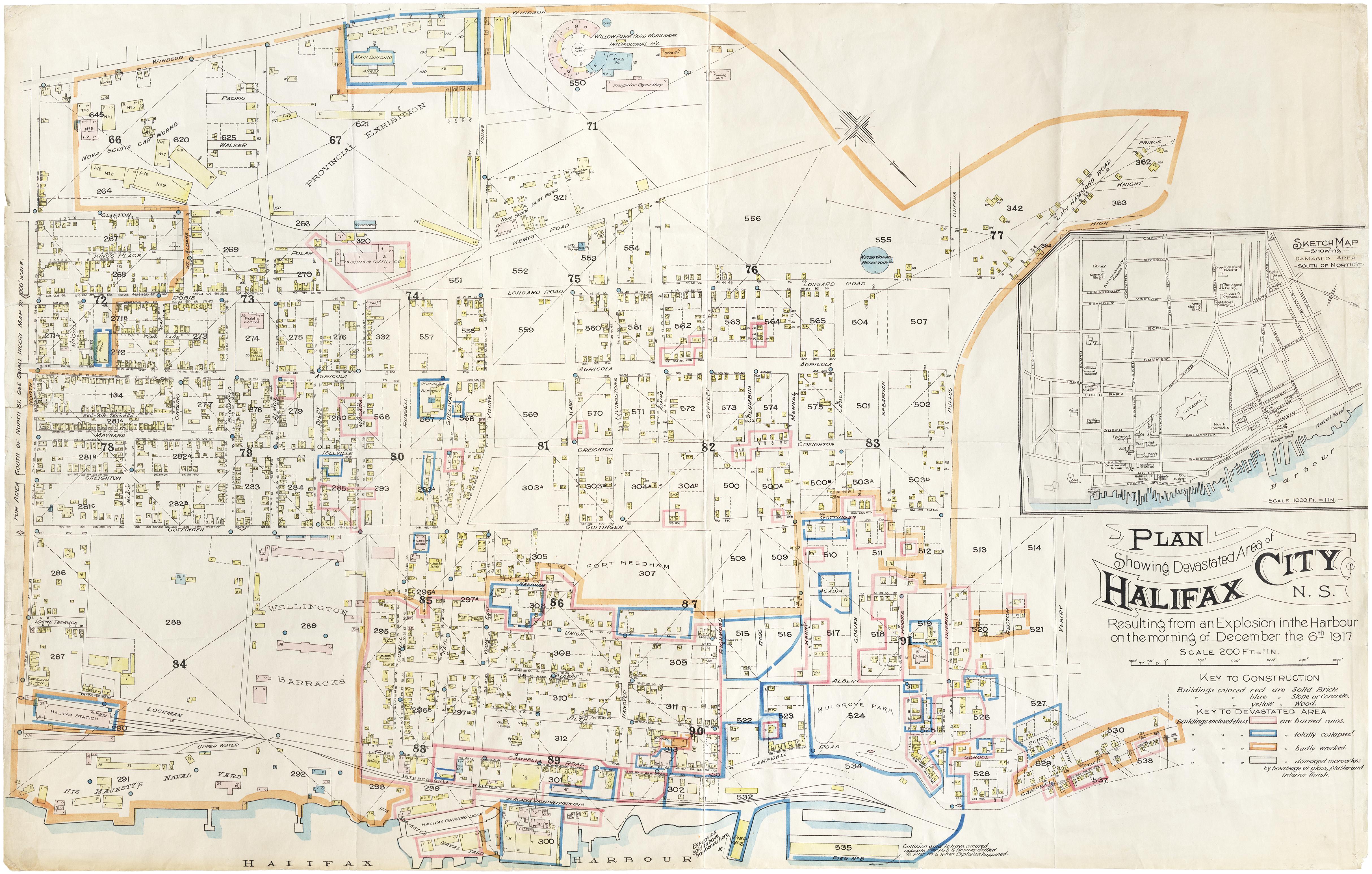

The Mont-Blanc exploded at 9:04:35 a.m., sending out a shock wave in all directions, followed by a tsunami that washed violently over the Halifax and Dartmouth shores. More than 2.5 square km of Richmond were totally levelled, either by the blast, the tsunami, or the structure fires caused when buildings collapsed inward on lanterns, stoves and furnaces.

Homes, offices, churches, factories, vessels (including the Mont-Blanc), the railway station and freight yards — and hundreds of people in the immediate area — were obliterated. Farther from the epicentre, Citadel Hill deflected shock waves away from the south and west ends of Halifax, where shattered windows and displaced doors were the predominant damage.

The blast shattered windows in Truro, 100 km away, and was heard in Prince Edward Island. The crew of the fishing boat Wave, working off the coast of Massachusetts, even claimed to have heard the boom rumbling across the ocean.

Author Laura Mac Donald describes the ferocity of the explosion in her book, Curse of the Narrows:

The air blast blew through the narrow streets, toppling buildings and crashing through windows, doors, walls, and chimneys until it slowed to 756 miles an hour, five miles below the speed of sound. The blast crushed internal organs, exploding lungs and eardrums of those standing closest to the ship, most of whom died instantly. It picked up others, only to thrash them against trees, walls, and lampposts with enough force to kill them. Roofs and ceilings collapsed on top of their owners. Floors dropped into the basement and trapped families under timber, beams and furniture. This was particularly dangerous for those close to the harbour because a fireball, which was invisible in the daylight, shot out over a 1–4 mile area surrounding the Mont-Blanc. Richmond houses caught fire like so much kindling. In houses able to withstand the blast, windows stretched inward until the glass shattered around its weakest point, sending out a shower of arrow-shaped slivers that cut their way through curtains, wallpaper and walls. The glass spared no one. Some people were beheaded where they stood; others were saved by a falling bed or bookshelf.… Many others who had watched the fire seconds before awoke to find themselves unable to see.

The blast shot vaporized sections of the Mont-Blanc upwards in a great fireball. The large shank of the ship's anchor was sent flying across the city and over the Northwest Arm, nearly 4 km away (where it remains to this day). The Imo was tossed like a toy onto the Dartmouth shoreline. Meanwhile, burning metal fragments of Mont-Blanc showered down on Halifax, along with a black rain of carbon particles.

People were also blown through the sky. Where and how they landed largely determined whether they lived or died. Charles Mayers, third officer of the vessel Middleham Castle, was picked up and dropped nearly 1 km from his ship, landing atop Fort Needham Hill in Richmond. "I was wet when I came down," Mayers said. "I had no clothes on when I came to, except my boots. There was a little girl near me and I asked her where we were. She was crying and said she did not know where we were. Some men gave me a pair of trousers and a rubber coat."

Did you know?

Casualties of the explosion included sailors from HMCS Niobe, one of the Royal Canadian Navy’s first two warships. Niobe’s captain had sent his team pinnace (ship’s boat) with seven volunteers to help the Mont-Blanc. When it exploded, Niobe’s pinnace and its crew were blown to pieces. The explosion badly damaged Niobe, but it was repaired and continued as a depot ship for a few years.

Death and Destruction

The north ends of Halifax and Dartmouth bore the brunt of the devastation. Dartmouth's north was sparsely developed, however the Mi’kmaq settlement at Turtle Grove — where Mi'kmaq families had lived for generations — was completely destroyed; those houses in Turtle Grove that were not knocked down by the shock wave were soon swamped by the tsunami.

Richmond was an apocalyptic scene: trees and telegraph poles were snapped; houses were turned into piles of splintered wood, or split open, partially collapsed, or on fire. On the waterfront, the railway yards were destroyed, as were a series of large piers that once jutted into the harbour. Even larger stone or concrete buildings, such as the Richmond Printing Company, were reduced to rubble. Bewildered survivors, including those injured or in shock, wandered or crawled amid the wreckage, trying to make sense of what had happened.

Across Halifax, there were miraculous stories of survival. And equally, stories of tragedy. Many children were killed on their walk to school that morning, or blinded by flying glass. Those that survived the blast stumbled home, only to find their houses shattered, or their parents dead or wounded, among the wreckage.

About 1,600 people died instantly, including hundreds of children. Roughly 400 more died from their injuries in the days that followed. The explosion and its flying debris decapitated some, took the limbs from others, and left many with burns, fractures and open wounds. Morgue records from 1918 show 1,631 known dead or missing — about a third of them under the age of 15. By 2004, the number of dead had been revised at 1,946.

Nine thousand more were wounded, including hundreds blinded or partially blinded by flying glass. (See also: Halifax Explosion and the CNIB.)

More than 1,500 buildings were destroyed and 12,000 damaged. Twenty-five thousand people were made homeless or lacked proper shelter after the explosion — a problem made worse by the winter blizzard that struck Halifax the next day. Total property damage amounted to an estimated $35 million.

Relief

Halifax's civilian administration was ill-equipped to respond to the disaster. Before the explosion, social services were few, and mostly offered by private charities, not government. The city's mayor was away at the time, so leadership of the immediate response fell to Deputy Mayor Henry Colwell. He himself had only a small police and fire service to call on, and to make matters worse the fire chief, Edward Condon, had been killed and the city's only fire pumper truck was destroyed.

Despite these challenges, Halifax could take advantage of legions of well-disciplined military personnel who happened to be in the city, providing a ready and organized workforce to bring aid and a semblance of order. The military response included crews from warships that either survived the blast, or arrived in the harbour in the days afterwards, who came ashore to help in the rescue and relief effort. Many homeless or wounded victims were also given shelter and medical care on board Canadian, American and other ships in the harbour.

Did you know?

Dr. Clement Ligoure, Halifax’s first Black doctor, was one of the unsung heroes of the Halifax Explosion. Ligoure treated hundreds of victims free of charge in the days and weeks after the explosion.

From across Halifax, survivors rushed to Richmond to rescue people trapped in homes, carry stunned and wounded residents to safety, hand out clothing and clear debris from roads. Local businesses donated supplies and offered work crews to help in the immediate aftermath. Rockhead Prison on Gottingen Street was opened up as a shelter for the homeless. Since the city's commercial undertakers couldn't cope with the number of dead, Chebucto Road School, just outside the blast area, was turned into a morgue. Meanwhile, city officials hastily organized committees that provided emergency food, shelter and transport — for delivering the injured to hospital and taking relief workers into devastated areas. The military was given full emergency powers to commandeer automobiles, control looting attempts and to regulate movement in and out of Richmond.

Relief workers and supplies soon flowed into Halifax from virtually every community across Nova Scotia. The explosion also made headlines around the world. Trains from throughout the Maritimes and from central Canada and New England soon brought medical aid, doctors, nurses, food, clothing, building materials and skilled labourers. Huge volumes of relief and assistance, organized in nearby Boston, and provided by the Massachusetts–Halifax Relief Committee, were particularly noteworthy. Many medical workers who came from Canada and the United States were later haunted by the horrors of the injuries they treated, particularly among children.

Money was raised through special appeals for Halifax, in towns and cities and from governments around the world as far away as Australia (whose national government gave $250,000). The funds donated by government, industry and individuals worldwide eventually totalled more than $20 million. The funds were administered from 1918 to 1976 by the Halifax Relief Commission — created by the federal government to oversee claims for loss and damage, rehousing and rehabilitation of explosion victims. The Commission took charge of most areas of relief and reconstruction work. It provided ongoing medical and psychological care; paid out cash for the medical, travel and living expenses of needy survivors; provided housekeepers for widowed parents who needed to return to work; or provided money for people whose wounds prevented them from working. The Commission also oversaw reconstruction of the city, including Canada's first public housing construction project — the Hydrostone development — in Richmond. It later became a pension board, dispensing funds to disabled dependents.

Inquiry and Prosecution

Halifax's angry survivors demanded answers — and scapegoats — in the wake of the tragedy. At first, there were rumours that German saboteurs were behind the explosion. However, a judicial inquiry — heavily influenced by the aggressive tactics of Charles Burchell, the lawyer hired to represent the owners of the Imo — quickly focused blame on three men: Aimé Le Médec, the Mont-Blanc's captain; Francis Mackey, the harbour pilot on board Mont-Blanc; and F. Evan Wyatt, the naval officer in command of the harbour. (Most of the Imo's crew, and its pilot William Hayes, had perished in the blast.) On 4 February 1918, Arthur Drysdale, the Nova Scotia judge presiding over the inquiry, found Mont-Blanc solely at fault for the disaster.

With the approval of many Haligonians, Le Médec, Mackey and Wyatt were arrested and charged with manslaughter. Despite several attempts to prosecute them, the charges were ultimately dropped for lack of evidence.

In 1919, the inquiry's conclusions were appealed to the Supreme Court of Canada, which declared that both Mont-Blanc and Imo were equally at fault. This verdict was upheld by the Judicial Committee of the Privy Council in London, at that time Canada's highest court of appeal.

Ultimately, no one was ever successfully prosecuted for failures leading to the explosion. Le Médec returned to France, where he continued his career as a mariner; Wyatt was sent elsewhere by the Navy; and Mackey remained in Halifax and continued working as a harbour pilot, despite the difficulties he faced amid public anger and suspicion.

In 1958, Mackey told CBC Radio: "[Imo] come out on his wrong side. Broke the rules, come on the wrong side of a steamer on the wrong side up above in the Narrows, and then come down on the wrong side again and struck me… There was no ship allowed to come out when a ship incoming was bound in. Had the right-of-way myself but she come out."

Memory

Memories of the Explosion lived on for decades among the survivors who witnessed it, many of whom told their stories of that terrifying day. One of the last surviving eyewitnesses was Kaye McLeod Chapman, only five years old at the time of the disaster. Despite the destruction to her home and her neighbourhood, Chapman credited her survival to the fact that she was holding a Bible and a Christian hymnbook in her hands at the moment of the blast — playing a pretend game of Sunday School with her dolls. A deeply religious woman throughout her life, Chapman died in New Brunswick in October 2017, aged 105.

There are numerous plaques, markers, pieces of embedded explosion wreckage, and gravestones scattered throughout Halifax that commemorate the disaster. One of the most obvious reminders is the city's famous Hydrostone neighbourhood — a series of housing blocks built in the once-devastated north end, using hydrostone bricks, to provide shelter for homeless victims. The neighbourhood's former name, Richmond, is now mostly forgotten.

Next door to the Hydrostone is Fort Needham Park, a grassy hill topped with a concrete memorial, where every year on 6 December, people gather above the Narrows to hear the ringing of the memorial's carillon bells, and to remember the victims of the disaster. A smaller memorial to the explosion also sits in Halifax's Fairview Cemetery. The graves of those who died are scattered in Fairview and other cemeteries across the city.

Perhaps the most poignant reminder of the tragedy, and the response to it, is the large Christmas tree cut every year from the Nova Scotia woods and erected in central Boston — a gift of thanks from the people of Halifax to a city that provided essential relief and support in the wake of the explosion.

Share on Facebook

Share on Facebook Share on X

Share on X Share by Email

Share by Email Share on Google Classroom

Share on Google Classroom