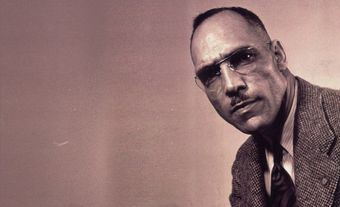

Clement Courtenay Ligoure, physician (born 13 October 1887 in Trinidad; died 23 May 1922 Port of Spain, Trinidad). Dr. Ligoure was Halifax’s first Black doctor and an unsung hero of the Halifax Explosion, as he treated hundreds of patients free of charge in his home medical office. Dr. Ligoure was also instrumental in the formation of the No. 2 Construction Battalion, Canada’s first and only all-Black battalion (see Black Canadians; Caribbean Canadians).

Early Years and Education

Not much is known about Clement Ligoure’s early life. What is known is Dr. Ligoure was born in Trinidad and emigrated first to New York City and then to Canada to attend medical school at Queen’s University in Kingston, Ontario. (See also Black Canadians; Caribbean Canadians.) Dr. Ligoure graduated in 1916. Two years later, in 1918, the university banned Black students from attending its School of Medicine. Black students would not be welcome back into the school again until 1965. (See also Racial Segregation of Black Students in Canadian Schools; Racial Segregation of Black People in Canada.)

Life in Halifax

Following graduation, Clement Ligoure moved to Halifax with the hopes of joining the war efforts (see First World War). At the time, Black men were being turned away at recruiting stations based on the colour of their skin (see Anti-Black Racism in Canada). Ligoure banded with Reverend William Andrew White and others to push for the Canadian Forces to allow Black men to enlist. In 1916, a segregated all-Black unit was proposed. Ligoure, White and others recruited Black soldiers across the country to join what would become the No. 2 Construction Battalion. Ligoure was eager to become the Battalion’s chief medical officer but was told by the department of defence that he had failed the medical exam by one point. While this was the explanation given, there was speculation that the real reason Ligoure was denied the role was that a Black man, at that time, could never be given the rank of a captain. The job instead went to Captain Dan Murray, grandfather of Nova Scotia singing great Anne Murray.

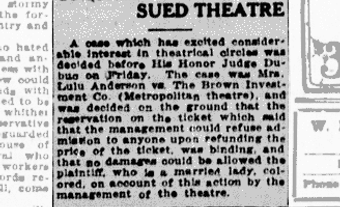

Ligoure was an active member of his North End Halifax community and spearheaded and/or supported several initiatives to combat racism and discrimination in Canada. While his hopes of joining the war efforts were dashed, he ended up taking on the role of publisher for a newsmagazine called the Atlantic Advocate. The opportunity arose after the founding publisher, W.A. DeCosta, left Halifax to become a member of the No. 2 Construction Battalion. The Atlantic Advocate was Nova Scotia’s first Black news publication and covered a variety of topics in the hopes of informing and uplifting African Nova Scotian issues and interests. (See also Magazines; Newspapers in Canada)

Ligoure also came to Halifax in the hopes of putting his medical degree to work locally. He quickly discovered that this was not an easy task for a Black man and was faced with racism and discrimination once again when he tried to obtain hospital privileges. Determined to practise within the City of Halifax, he decided to set up a private clinic in his home at 166 North Street (now 5812-14 North Street) in the North End of Halifax. He called it the Amanda Private Hospital, which was named after his mother.

The Halifax Explosion

Clement Ligoure had not been in Halifax long when its residents were faced with what would become one of the most well-known and devastating explosions in Canadian history (see Halifax Explosion). On the morning of 6 December 1917, a French cargo ship called the SS Mont-Blanc collided with a Norwegian vessel, known as the SS Imo, in the Halifax Harbour. Upon making contact, the Mont-Blanc, which was carrying high explosives, caught fire and exploded. This blast was not only heard, it destroyed the Richmond district of Halifax and the results were shattering. The explosion killed approximately 2,000 people and injured 9,000.

Following the explosion, the Amanda Private Hospital began filling with injured civilians, many of whom had been turned away from the main hospital in the city. Ligoure was the only doctor in the Cotton Factory and Willow Park district, and he worked around the clock tending to the wounded. He was assisted only by his housekeeper and a Pullman porter named H.D. Nicholas, who was boarding with Ligoure at the time. On the first night, seven people slept on blankets on the floor of Ligoure’s office. Despite the warning of a potential second explosion that could further devastate the area, Ligoure continued to work. And when the injured could not travel to him, he travelled to the injured during all hours of the night. After continuing in this manner for several days, an exhausted Ligoure went to city hall and met with Lieutenant Ryecroft to plead for the urgent need of a dressing station in his district. Ligoure’s request was approved, and several nurses and military personnel were sent to support him and the patients of Amanda Private Hospital. The No. 4 dressing station tended to around 180 people per day and this intensity continued throughout most of the remainder of December.

Ligoure continued to support relief efforts and would tend to up to 51 cases at a time due to ongoing medical conditions following the explosion. Throughout this time, it is believed he did not charge one single patient.

Legacy and Commemorations

Clement Ligoure eventually closed Amanda Private Hospital and bought a home in Schmidtville. Not long after, in 1922, Ligoure passed away at 34 years of age. For decades, there was no known information about Ligoure’s death. In 2023, Halifax researcher and historian Joel Zemel published new findings about Ligoure. Zemel found Ligoure’s obituary and funeral announcement in the Port of Spain Gazette and was able to describe — 101 years after Ligoure’s death — his final years and the circumstances of his passing. An obituary from 30 May 1922 recounts that Ligoure contracted malignant malaria while visiting one of his brothers in Tobago. After being transported to the Colonial Hospital in Trinidad, Ligoure died on 23 May 1922.

Ligoure’s life and legacy has been honoured in a number of ways and people are still learning more about this incredible hero of the Halifax Explosion. In 2020, playwright David Woods wrote a play called Extraordinary Acts, which highlights the experiences of the Black community during the explosion. (See also People on the Margins of the Halifax Explosion.)

In 2021, Doctors Nova Scotia announced the Dr. Clement Ligoure Award. The award was created to recognize “exemplary service during a medical crisis.” The inaugural award recipient was Dr. Robert Strang, Nova Scotia’s chief medical officer of health.

Development Options Halifax, a group located in the City of Halifax, is determined to preserve what remains of the once bustling Amanda Private Hospital. As of 2022, the group petitioned to stop the demolition of the building. Similarly, Friends of Halifax Common submitted an application to the Halifax Regional Municipality for the former home and office of Nova Scotia’s first Black physician to be designated a historic property. As of January 2023, the Halifax regional council voted in favour to register the building as a heritage property. (See also Heritage Conservation.)

Share on Facebook

Share on Facebook Share on X

Share on X Share by Email

Share by Email Share on Google Classroom

Share on Google Classroom