Elizabeth Arden (née Florence Nightingale Graham), entrepreneur, founder of Elizabeth Arden Inc. (born 31 December 1881 in Vaughan Township, ON; died 18 October 1966 in New York City, NY). Arden was an innovator in the cosmetics and beauty culture industry. She used mass marketing to promote her products and change popular perceptions of makeup (see Advertising). Her clientele included British royalty and celebrities such as Marilyn Monroe and Elizabeth Taylor. She rose from humble beginnings to being one of the wealthiest women in the world.

Early Life and Education

Elizabeth Arden was born Florence Nightingale Graham. She was the daughter of William and Susan (née Tadd) Graham, immigrants from the United Kingdom (see Immigration to Canada). Little is known of Florence’s early years due to a lack of documentation and details that she fabricated later in life. A surviving official record testifying to her place and date of birth is a statutory declaration signed by her brother, William Pearce Graham, in 1933. Susan Graham died when Florence was six years old. William Graham worked at various jobs, but the family struggled financially. Florence received a basic education but was obliged to go to work at a young age, finding employment at different times as a cashier, secretary and dental assistant. She briefly attended a nursing school in Toronto but did not complete her training.

Introduction to the Beauty Industry

In 1907 or 1908, Florence moved to New York City, where her brother, William, was already living. She was employed by Eleanor Adair, a pioneer in the cosmetics and beauty industry whose salons in New York, London and Paris catered to women of high social standing. In the short time she worked for her, Florence apparently learned to apply Adair’s range of beauty treatments, which included massage, facials, eye treatments, weight reduction and electrolysis.

Transformation to “Elizabeth Arden”

In 1909, Florence left her job with Eleanor Adair and entered a partnership with another beautician named Elizabeth Hubbard. They opened a salon on New York’s Fifth Avenue with Elizabeth Hubbard’s name on the window. The partnership was short-lived and Florence became sole operator of the salon. She kept the name Elizabeth on the window but replaced the surname with Arden, allegedly because her favourite poem was Alfred, Lord Tennyson’s “Enoch Arden” (1864). It is also popularly recounted that Florence took the name from railroad baron Edward Henry Harriman’s estate, which was called Arden. Although Florence would continue to use her birth name for some purposes, professionally she would now be known as Elizabeth Arden.

Building an Empire

Elizabeth Arden’s establishment, which she called Salon d’Oro, was an overnight success. She was a skilled beautician and an astute businessperson. She advertised extensively, promoting her treatments and newly developed cosmetics (see Advertising). Arden sold products such as Venetian Pore Cream and Venetian Eyelash Grower through mail order and convinced major department stores such as Stern Brothers in New York to carry them. She took trips to Paris and London where she visited beauty salons in search of new products and treatments and to observe how the fashionable women of Europe were using cosmetics. She brought perfumes and other beauty products back to New York for analysis. In 1913, Arden enlarged her New York location and opened another Salon d’Oro in Washington DC. It would be followed by salons in Boston, San Francisco, Palm Beach and Detroit, as well as a beauty product laboratory in New York. In 1920, Arden opened a salon in Paris. Over the following decade she expanded her business with salons opening in London, Cannes, Biarritz, Madrid, Rome and Berlin. This was the beginning of what would one day be a global corporate empire. As her company grew, Elizabeth Arden found herself in competition with such beauty business rivals as Helena Rubinstein and Dorothy Gray. Arden had a reputation for being headstrong and ruthless in business, and the rivalries were fiercely competitive.

Beauty Culture Revolution

Elizabeth Arden played a major role in revolutionizing beauty culture and the public perception of it, especially in North America. Prior to the 1920s, makeup, and more specifically its heavy application, was considered improper and linked with moral failings, as it was associated with sex workers and women of the lowest social class. Arden was among the beauty “experts” who made makeup respectable.

Before her products were available, women could choose from only two shades of face powder, white and pink; and many cosmetics, such as hand cream, were homemade. Arden introduced new products such as mascara and eyeshadow. She sold specially designed chin straps and other equipment as beauty aids. Arden’s product range eventually expanded to include shampoos, soaps, deodorants, bath salts, talcum powder and hair removers. She published booklets, such as “The Quest of the Beautiful,” that provided information on how to conduct home treatments. She successfully made beauty culture part of a healthy lifestyle that included exercise, diet and weight control. Arden’s spas, such as her Maine Chance Farm in Mount Vernon, Maine, were the first establishments of their kind to become destination spas. Elizabeth Arden has been quoted as saying, “I want to keep people well and young and beautiful,” and “I don’t sell cosmetics, I sell hope.”

Personal Life, Later Years and Death

In 1915, Elizabeth Arden married Thomas Jenkins Lewis, a banker whom she made general manager of her company. Although the business benefitted from Lewis’s professional insight, Arden would not permit him to own stock. They were divorced in 1934 and Lewis went to work for Helena Rubinstein, another entrepreneur in the cosmetics industry. In 1942, Arden married Prince Michael Evlanoff, a Russian émigré. That marriage ended in divorce in 1944, and Arden did not marry again. She had no children.

Elizabeth Arden was fond of racehorses and owned several thoroughbreds (see Thoroughbred Racing). In 1945, her horses won a $589,170 at the track. One of her thoroughbreds, named Jet Pilot, won the Kentucky Derby of 1947. Arden’s involvement in horse racing got her photograph on the May 1946 cover of TIME magazine.

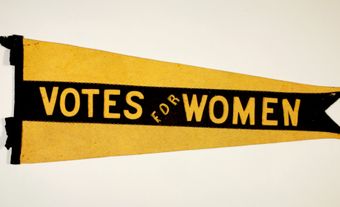

Arden supported the women’s suffrage movement and she marched with the suffragettes in 1912. (See also Women's Suffrage in Canada.) It is popularly said that Arden supplied fellow marchers with red lipstick as a gesture of solidarity. However, there is no evidence that actually happened. During the Second World War she developed a special line of cosmetics for women serving in the military (see Women in the Military). She also contributed to charities such as the Red Cross. In 1962, the government of France awarded Arden the Légion d’honneur in recognition of her contribution to the cosmetics industry. She died of complications following a heart attack.

Share on Facebook

Share on Facebook Share on X

Share on X Share by Email

Share by Email Share on Google Classroom

Share on Google Classroom