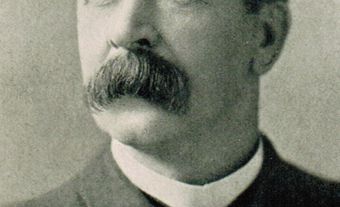

Frances Gertrude McGill, teacher, bacteriologist, forensic pathologist (born 18 November 1882 in Minnedosa, MB; died 21 January 1959 in Winnipeg). McGill was Canada’s first female forensic pathologist and a pioneer in the field. She assisted police in solving numerous difficult criminal cases and unusual deaths, earning the nickname “the Sherlock Holmes of Saskatchewan.” She is often regarded as the first female member of the Royal Canadian Mounted Police (RCMP). Her personal motto is said to have been “Think like a man, act like a lady and work like a dog.”

Early Life and Education

Frances McGill grew up on a small farm in southwestern Manitoba with three siblings. In 1900, both of her parents, Edward McGill and Henrietta Wigmore, died of typhoid fever after drinking contaminated water at a county fair. (See also Salmonella.) McGill attended the Normal School (now the Manitoba Teachers’ College) in Winnipeg and taught at a rural school (see Normal Schools; Rural Teachers in Canada). She considered a career in law but decided to follow the example of two of her siblings and study medicine (see Medical Education). She enrolled in the University of Manitoba and took teaching jobs during the summer to pay for her education. She graduated with a degree in medicine in 1915 and received the Dean’s Prize and the Hutchinson Gold Medal for having the highest academic standing. McGill interned for a year at the Winnipeg General Hospital and then undertook postgraduate studies at the Provincial Laboratory.

Provincial Bacteriologist

As an expert in bacteriology, Frances McGill accepted a position as the provincial bacteriologist for the Saskatchewan Department of Health in Regina in 1918. This was when the influenza pandemic, more commonly known as the Spanish flu, was beginning to sweep across Canada and the world (see 1918 Spanish Flu in Canada). As provincial bacteriologist, McGill was also responsible for treating venereal disease (see Sexually Transmitted Infections), especially among soldiers of the Canadian Expeditionary Force returning home from the European theatre of the First World War. Her office and laboratory were on the top floor of the Saskatchewan Legislative Building. Animals used for research were kept in cages on the roof.

Pioneer Pathologist

In 1920, Frances McGill moved to the post of provincial pathologist. Two years later, she was appointed director of the Provincial Laboratory, which meant she would have the task of investigating suspicious deaths through the application of forensic science. The fact that it was a relatively new field in Canada meant that McGill, as a qualified professional, was able to avoid the obstacles that women typically faced in male-dominated scientific fields. Nonetheless, she had to prove her professional capabilities to the RCMP, who were seemingly reluctant to accept a female pathologist.

As the RCMP would not establish its first forensic lab until 1937, McGill had to undertake all of the forensic autopsies and related analysis and evidence preservation for police forces and the RCMP across Saskatchewan. ( See also Law of Evidence.) Investigations required her to cover thousands of kilometres at all hours, often in extreme weather. Her work took her all over the province, sometimes to remote locations and even to the Arctic Circle. When she could not reach a destination by car, she would travel by horseback, dogsled, floatplane or snowmobile. In 1934 alone, McGill made 43 trips out of town for these criminal investigations. McGill proved to be a strong, robust person whose dedication, energy and stamina, as well as her ability to undertake gruesome investigations unflinchingly, impressed her male colleagues.

McGill’s workload decreased after the RCMP set up its first official laboratory for forensic detection in 1937. In 1942, she retired from the Provincial Laboratory to go into private medical practice, specializing in skin ailments and allergies. However, in 1943, Dr. Maurice Powers, director of the RCMP’s forensic laboratory in Regina, died in a plane crash and McGill was called upon to serve as his replacement. In her capacity as director, McGill continued to conduct investigations across Saskatchewan. She also lectured and trained police officers and detectives in medical jurisprudence, pathology and toxicology. She taught students how to study crime scenes, distinguish between animal and human blood, and collect and preserve evidence. She advised students on the importance of critical thinking when examining a crime scene and documents such as death certificates. In her determination to uncover the facts of a case, she was both medical investigator and police detective. When giving evidence in court, McGill was thorough, though she could allegedly be impatient with lawyers and pointed in her remarks to them.

Noteworthy Cases

In 1932, police were certain that farmer Joseph Shewchuk of Lintlaw, Saskatchewan, who had been found dead with a gunshot wound to the head, had been murdered. They charged a neighbouring farmer with the crime. McGill’s examination of the evidence proved that the victim had committed suicide by shooting himself and that the blood on the accused’s clothing was blood from a calf.

In the South Poplar case of 1933, police believed that a hitchhiker whose body had been found frozen in a field had been killed by a blow to the head. McGill proved that the victim had died from a heart attack and that what appeared to be trauma to the skull had, in fact, been the result of a childhood case of rickets combined with the victim’s exposure to extreme cold after consuming alcohol.

In the 1936 Bran Muffin case, McGill proved that a woman had murdered her grandparents while trying to poison her father. Prior to her investigation, a crime had not even been suspected because there had been no obvious motive.

Later Career

Frances McGill stepped down when the RCMP hired a new, permanent laboratory director, Dr. C.D.T. Mundell. According to a 2013 article by Susanna McLeod in The Kingston Whig Standard, Mundell suggested that “this lady be given some title and official position with the Force … as a reward for the very excellent service she has given and also to ensure that her services will be available if necessary in the future.” McGill was subsequently appointed honorary surgeon to the RCMP on 16 January 1946.

In 1952, McGill toured England as the only female member of the RCMP and was permitted to inspect the forensic laboratories of Scotland Yard. McGill never married and reportedly said that she would not abandon a rewarding career for a man. McGill continued serving as a consultant to the RCMP until her death in 1959.

Legacy

Frances McGill was inducted into the Canadian Science and Engineering Hall of Fame in 1999. Lake McGill in northern Saskatchewan was named after McGill following her death in 1959. McGill was the inspiration for the French-language novel La pathologiste : Dr. Lesley Richardson enquête (2022) by Elisabeth Tremblay.

Share on Facebook

Share on Facebook Share on X

Share on X Share by Email

Share by Email Share on Google Classroom

Share on Google Classroom