Daphne Odjig, CM, OBC, visual artist (born 11 September 1919 on Wiikwemkoong Unceded Territory, Manitoulin Island, ON; died 1 October 2016 in Kelowna, BC). Odjig was a founding member of the 1970s artists’ alliance Professional Native Indian Artists Inc., also known as the Indian Group of Seven.

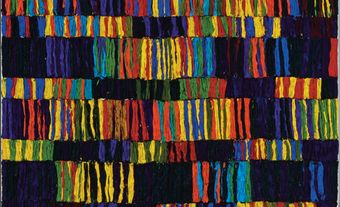

Her artistic career spanned six decades and includes lyrical legend paintings, personal reflective memories, and trenchant historical and political critiques. Experimental and creatively fearless, Odjig’s styles and media varied widely with her subject matter. Fluid calligraphic lines characterized her early narrative paintings in t he 1960s, while her history paintings in the 1970s were densely expressive. Odjig’s elegiac colour studies of the British Columbia forests were featured in her work in the 1980s. In her long career, Odjig combined her originality as a painter with her social awareness as a feminist to create a body of work that helped bring an Indigenous voice to the foreground of contemporary Canadian art.

Early Life

Daphne Odjig is the first-born child of Potawatomi First World War veteran Dominic Odjig and his English war bride, Joyce Peachy. Odjig’s earliest artistic influence was her paternal grandfather Jonas Odjig, a stone carver and storyteller. When she contracted rheumatic fever at age 13 and was forced to withdraw from school, her education fell mostly to her grandfather who instructed her in drawing, carving and the oral traditions of her family. Luckily hers was an artistic, musical family that gave her a strong foundation in sketching and drawing, an ambition to continue her education and a love of painting.

When she moved to Toronto during the Second World War, Odjig spent her weekends teaching herself to paint by observing and copying works of the masters at the Royal Ontario Museum and the Art Gallery of Toronto (now the Art Gallery of Ontario). Her early oil paintings were well-received and show the influence of Picasso, Matisse, and the Impressionists.

Indigenous Art Focus

In 1964, Odjig was invited to attend the fourth annual powwow at Wiikwemkoong and experienced a life and career-altering awakening. As a young adult in northern Ontario she had encountered racial discrimination and faced barriers to employment because of her Anishinaabe name and appearance. In response, she began to identify herself instead as Daphne Fisher and tried to suppress her Indigenous identity. While dancing with her relatives to the beat of the powwow drum, though, she suddenly understood herself as an Indigenous woman. The exuberant pride and defiance she witnessed and participated in at the powwow inspired her to accept and honour her heritage. She chose to redirect her artistic work to celebrate and investigate the history and traditions of her people. Her painting style became more graphic, incorporating the sweeping calligraphic lines she had learned from her stone carver grandfather.

Her subject matter also changed as she illustrated traditional legends, such as the old trickster tales of Nanabush, and the darker histories of upheaval, land loss and survival. In 1966, she and her husband Chester Beavon, who was a community development officer for the Department of Indian Affairs, were posted to a small Cree settlement in northern Manitoba. The Chemawawin Cree at Easterville had recently been displaced from their homeland to make way for a dam and generating station. Inspired by the people’s struggle to cope with the disorder, poverty and confusion their relocation had caused, Odjig made a series of pen and ink drawings to document the daily life of the community. The intimacy and force of these drawings encouraged her to probe the realities of Indigenous people in Canada even further. (See also Social Conditions of Indigenous Peoples in Canada.)

Artistic Career

Daphne Odjig’s first solo exhibition at the Lakehead Art Centre in Thunder Bay in 1967 and a second in Brandon, Manitoba in 1968 brought her work to wider public attention. Commissions and larger projects followed. She completed a series of illustrations for Dr. Herbert Schwarz’s book Tales From the Smokehouse in 1968, a collage Earth Mother for the Canadian Pavilion at Expo ’70 in Osaka Japan, and a large-scale mural The Great Flood for Peguis High School in Manitoba in 1971. During that year she established Odjig Indian Prints of Canada Ltd. and a small craft shop at 331 Donald Street in Winnipeg. There, she distributed prints of her drawings and works by other Indigenous artists struggling to participate in the local art market. By 1974, the craft shop had expanded and was renamed the New Warehouse Gallery. It was the first Indigenous-owned art gallery in Canada.

The Warehouse was a convivial setting where Indigenous artists could meet to talk about art and organize projects. They also voiced their concerns and aspirations about the place of Indigenous art in the Canadian art world. Until that time, the artistic production of First Nations peoples was seen as little more than exotic handicraft to be housed in museums and was rarely exhibited as fine art. The rowdy group at the Warehouse was determined to change that perception and formed a collective called Professional Native Indian Artists Inc. to further their goals. Daphne Odjig, Alex Janvier, Jackson Beardy, Eddy Cobiness, Norval Morrisseau, Carl Ray and Joseph Sanchez began to organize group shows in venues across Canada and were soon dubbed "The Indian Group of Seven." Though the group was relatively short-lived, its ideas and influence endured and were critical to the early development of contemporary Indigenous art and curatorial practice in Canada.

Meanwhile, Odjig’s personal artistic practice continued to expand. She began to make murals and large paintings depicting historical events and legends that were imbued with themes of cultural survival and regeneration. These narrative works were explorations of personal and collective memory that challenged national stereotypes of Indigenous life and drove her painting technique. The mature Odjig was an experimental and dynamic painter. She eschewed the structural norms of Norval Morrisseau’s Woodland style. Odjig began to break the traditional black form line and disrupt the flat planes of colour that typified Morrisseau‘s paintings. She developed several distinct visual languages and graphic styles that she deployed across a number of thematic interests and concerns. In Odjig’s long career she painted about family life and colonial history. She produced complex abstractions that derive from Anishinaabe stories, and she created art that responded to the ecological urgencies of the forests of British Columbia where she lived since 1978.

Legacy

Daphne Odjig’s active commitment to Indigenous artists and their cultural production was a formative influence during the 1960s and 1970s when Indigenous communities were faced with economical and social adversity in Canada. Her art, which speaks from a feminist, Indigenous and aesthetically engaged perspective, continues to contribute to the Canadian narrative. Odjig contributed significantly to the visual arts community and to the cultural survival and professional success of Indigenous artists in Canada.

Awards and Honours

Daphne Odjig has received numerous awards and accolades, including many honourary doctoral degrees from universities across Canada.

She was appointed to the Order of Canada in 1986 and received the Governor General’s Award in Visual and Media Arts in 2007.

Odjig was the subject of a solo exhibition at the National Gallery of Canada, The Drawings and Paintings of Daphne Odjig: A Retrospective Exhibition, in 2009.

Share on Facebook

Share on Facebook Share on X

Share on X Share by Email

Share by Email Share on Google Classroom

Share on Google Classroom