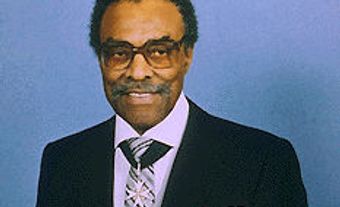

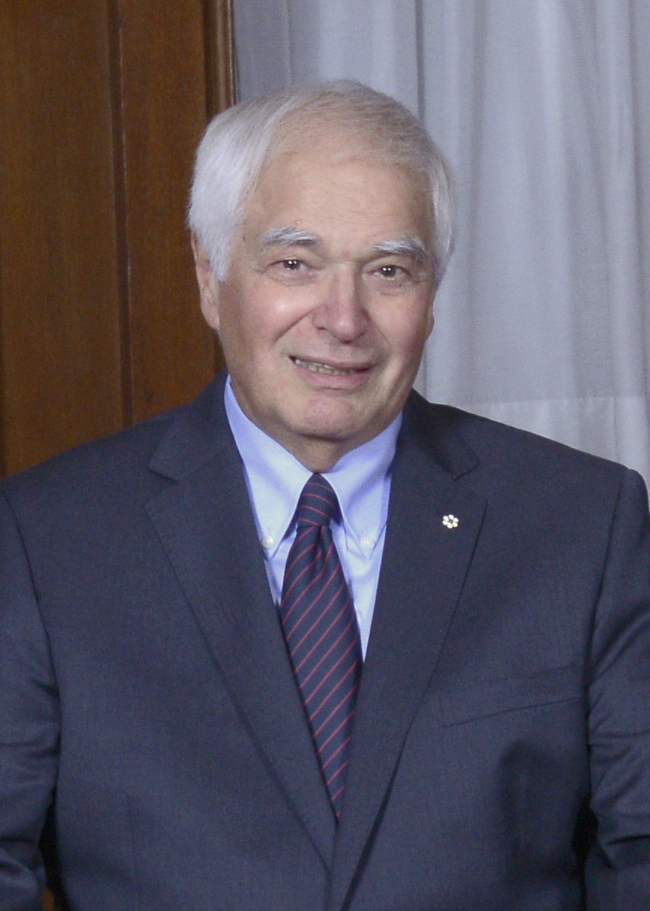

James Karl Bartleman, OC, OOnt, diplomat, author, lieutenant governor of Ontario 2002–07 (born 24 December 1939 in Orillia, ON; died 14 August 2023). James Bartleman spent nearly 40 years as a career diplomat. He served as high commissioner and ambassador to many countries, including South Africa, Cuba and Israel. He was also a foreign policy advisor to Prime Minister Jean Chrétien. A member of the Mnjikaning First Nation, Bartleman became Ontario’s first Indigenous lieutenant-governor in 2002. He was known for his advocacy for literacy and education in Indigenous communities and his efforts to end the stigma around mental health issues.

Early Life

Bartleman was born in Orillia, Ontario. His mother, Marie Simcoe, was Chippewa, from the Mnjikaning First Nation. She lost her Indian Status due to provisions of the Indian Act when she married Scottish Canadian Percy Bartleman. (See also Indigenous Women and the Franchise.)

The family moved to Port Carling, Ontario, in 1946. They spent summers in a tent close to the dump and wintered in a rented, ramshackle house. Bartleman’s father was a labourer and sold fish to local restaurants. His mother fought depression, something Bartleman later associated with the difficulty of balancing Indigenous and non-Indigenous worlds. He faced similar challenges as he dealt with racism and discrimination in the small town. He later recalled the wounds left from being called “dirty half-breed” as a youth. Despite this, he came to embrace his Indigenous heritage. “I thought it gave me, as an individual, a much richer life, knowing what Aboriginal life was like,” he said.

Trips to the local library with his father, an avid reader, opened new worlds to Bartleman and instilled a love of learning. Port Carling’s small school did not include Grade 13 (then the final year of high school), which would have ended Bartleman’s formal education. However, he had spent the summers of his youth working for American Robert Clause, the chair of the Pittsburgh Plate Glass Company and a Muskoka cottager. In 1958, Clause offered to fund not only a move to London, Ontario, so that Bartleman could complete high school, but his university education as well.

Education

Bartleman enrolled in history at the University of Western Ontario (now Western University) in London, where he again confronted racism and discrimination. As the only Indigenous student at the university, he soon observed “that mainstream Canadians were uncomfortable with Indians.” He recalled that the Canadian history lectures he attended often made generalizations about Indigenous peoples. Indigenous peoples’ interactions with European settlers were simplified, and their contributions to the nation’s development were largely erased. Still, Bartleman immersed himself in this new learning environment. He focused on literature and history and graduated in 1963 with an honours bachelor degree.

After teaching for a year in southwestern Ontario, Bartleman set off for Europe. He backpacked across the continent, travelling to countries such as Spain, Norway and France. He stopped to teach for a time in England and at The Hague. He also worked in centres for travelling students. His year abroad included events that helped inspire his career in the Canadian Foreign Service.

On 6 December 1964, Bartleman arrived for an organ recital at St. Paul’s Cathedral in London. Instead, he found himself in the audience for a speech by American civil rights leader Martin Luther King, Jr. King’s words resonated with Bartleman, stoking his growing belief that peace and co-operation were messages he wanted to spread. The next month, he was among the throngs lining London’s streets for Sir Winston Churchill’s funeral procession.

Diplomatic Career

Bartleman entered the Foreign Service in 1966. He took a position with the Department of Foreign Affairs and International Trade. This began nearly four decades of public service and world travels. In 1972, as acting high commissioner, he opened Canada’s first diplomatic mission in the newly independent Republic of Bangladesh. Bartleman was named to numerous diplomatic posts over his career, including ambassador to Cuba (1981–83). He was simultaneously high commissioner to Cyprus and ambassador to Israel from 1986 to 1990. He then served as ambassador to the North Atlantic Council of NATO for four years.

In 1994, Bartleman became foreign policy advisor to Prime Minister Jean Chrétien and assistant secretary to the cabinet for foreign and defence policy, Privy Council Office. Relations with several nations in Africa were especially tense in the mid-1990s, a period that included the Rwandan genocide of 1994. (See also Canadian Peacekeepers in Rwanda.) Bartleman later stated that he wished he had done more as the prime minister’s advisor. He also felt that Canada — like the United Nations (UN) — had been tarnished by its relative inaction in Rwanda. Bartleman worked with General Roméo Dallaire, commander of the UN’s Rwandan mission, and later recalled finding “it difficult to look into Dallaire’s eyes.” In 1996, hoping to avoid a similar situation in Zaire (Congo), the Canadian government — with Bartleman playing a key role — tried to organize an international rescue mission. However, the international community largely rejected the mission.

Bartleman served with the Chrétien government until 1998. In 1998, he served for one year as the high commissioner to South Africa. He then moved to the high commission in Australia (1999–2000). From 2000 until 2002, he was ambassador to the European Union.

Lieutenant-Governor of Ontario

On 7 March 2002, Bartleman was installed as Ontario’s 27th lieutenant-governor. He was the province’s first Indigenous vice-regal. He focused on three initiatives during his time in office: fighting racism and discrimination; championing Indigenous youth education and literacy; and eliminating the stigma around mental health issues.

During his first tours of Northern Ontario communities as lieutenant-governor, Bartleman noticed that the region’s school libraries had few books. In response, he established a book drive in 2004. Around 900,000 books were delivered to schools. Fly-in communities were prioritized for delivery. A second drive in 2007 included deliveries to Nunavut and northern Quebec.

In 2005, Bartleman initiated a twinning program between Indigenous and non-Indigenous schools in Ontario and Nunavut to encourage cultural understanding and community-building. Students participated in exchanges and pen-pal programs. There were also supply drives for educational resources, including books and musical instruments.

In July 2005, Bartleman announced the creation of literacy camps for Indigenous communities in northwestern Ontario. The camps also included sports and Indigenous language and culture. In 2006, the camps expanded to fly-in communities. About 3,500 children and youth across the region enrolled. Camp-goers became members of Club Amick, a reading program that eventually included 5,000 Indigenous participants.

Bartleman’s literacy initiatives were meant to help build youth esteem and provide opportunities. But he believed more should be done to improve mental health in Northern Ontario’s Indigenous communities. He therefore publicly shared his own experiences to lessen the shame often associated with mental illness. This included witnessing his mother’s struggles as well as his own fight with clinical depression. Bartleman’s candidness extended to the post-traumatic stress and depression he suffered after surviving a brutal beating and armed robbery in South Africa in 1999. “I managed to escape with my life,” he said, “but fell into a deep depression. I entertained suicidal thoughts… I wasn’t too ashamed to seek help.” With this openness he hoped to alleviate the stigma around mental illness that keeps many people from getting treatment.

Air India Bombing

In 1983, Bartleman was named head of intelligence for the Department of Foreign Affairs (now Global Affairs Canada). He was in the position at the time of the Air India bombing in June 1985. The terrorist bombing of Flight 182, which took off from Toronto’s Pearson Airport, killed 329 people, including 280 Canadians. Sikh separatists from British Columbia planned the attack. The Canadian government began an inquiry into the official response to the bombing in May 2006.

In May 2007, Bartleman (then lieutenant-governor of Ontario) testified before the Air India commission. He claimed to have seen an intelligence report in the days before the tragedy warning of an imminent attack on Air India. He stated that he had discussed it with an RCMP official but with none of his superiors in Foreign Affairs. He did not share this information for some 20 years. Bartleman’s disclosure rocked the inquiry. He was criticized for not coming forward with the information sooner. Several intelligence and RCMP officials questioned the accuracy of his recollections. The inquiry’s final report found major lapses in communication between Canada’s government agencies, the RCMP and the intelligence community. Bartleman apologized publicly to the victims’ families after his appearance before the commission.

OCAD University Chancellor

Bartleman completed his term as lieutenant-governor of Ontario in September 2007. He was then named chancellor of the Ontario College of Art and Design (now OCAD University). He served in the position until 2012.

Author

Bartleman was a bestselling author of both non-fiction and fiction. He detailed his diplomatic and personal life in four memoirs. Out of Muskoka (2002) and Raisin Wine (2007) are reflections on his childhood in Port Carling. He also touches on the challenges of navigating non-Indigenous and Indigenous cultures, dealing with racism and discrimination and embracing his Indigenous heritage. He donated the proceeds from Out of Muskoka to the National Aboriginal Achievement Foundation. The proceeds from Raisin Wine were used to ship books to northern communities. In On Six Continents (2004) and Rollercoaster (2005), Bartleman shares his decades as a diplomat and foreign policy advisor. The latter also focuses on his time working with the Chrétien government.

Bartleman also mined his life experiences for works of fiction. His first novel, As Long as the River Flows (2011), explores the generational impact of Canada’s residential school system on an Indigenous family in Northern Ontario. Exceptional Circumstances (2015) is a novel of diplomatic intrigue set amid the October Crisis in 1970.

Personal Life

While posted to NATO headquarters in Brussels, Bartleman met his wife, Marie-Jeanne Rosillon. They married in 1975 and had three children.

Honours

Bartleman was the honorary patron for numerous organizations. These include the Mood Disorders Association of Ontario, the Institute of Mental Health Research and the Centre for Addiction and Mental Health (CAMH).

In 2008, the Ontario government established the James Bartleman Indigenous Youth Creative Writing Awards in recognition of Bartleman’s dedication to encouraging Indigenous youth literacy.

Awards

- National Aboriginal Achievement Award in Public Service (1999)

- Member, Order of Ontario (2002)

- Queen Elizabeth II Golden Jubilee Medal (2002)

- Dr. Hugh Lefave Award, Ontario ACT Association (2003)

- Courage to Come Back Award, CAMH (2004)

- Arthur Kroeger College Award in Ethics in Public Service, Carleton University (2007)

- Joseph Brant Award (Raisin Wine), Ontario Historical Society (2008)

- National Child Day Award, Canadian Institute of Child Health (2008)

- Officer, Order of Canada (2011)

- Queen Elizabeth II Diamond Jubilee Medal (2012)

Honorary Degrees

- Honorary Doctorate, Western University (2002)

- Doctor of Laws, York University (2003)

- Doctor of Laws, Laurentian University (2004)

- Doctor of Laws, Algoma University (2004)

- Doctor of Laws, Queen’s University (2004)

- Honorary Doctorate, Ryerson University (2005)

- Doctor of Laws, University of Windsor (2005)

- Doctor of Letters, McGill University (2006)

- Doctor of Education, Nipissing University (2006)

- Doctor of Laws, Wilfrid Laurier University (2007)

- Honorary Doctorate, McMaster University (2009)

- Honorary Doctorate, Carleton University (2013)

- Doctor of Laws, University of Toronto (2016)

Share on Facebook

Share on Facebook Share on X

Share on X Share by Email

Share by Email Share on Google Classroom

Share on Google Classroom