Mi’kmaq (Mi’kmaw, Micmac or L’nu, “the people” in Mi’kmaq) are Indigenous peoples who are among the original inhabitants in the Atlantic Provinces of Canada. Alternative names for the Mi’kmaq appear in some historical sources and include Gaspesians, Souriquois and Tarrantines. Contemporary Mi’kmaq communities are located predominantly in Nova Scotia and New Brunswick, but with a significant presence in Quebec, Newfoundland, Maine and the Boston area. In the 2021 census, 70,640 people claimed Mi’kmaw ancestry. In July 2022, the Mi'kmaq language was recognized as the first language of Nova Scotia.

Traditional Territory

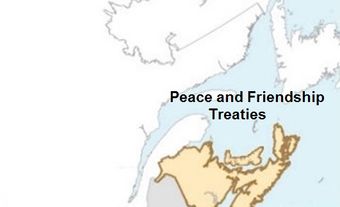

Mi’kmaq are among the original inhabitants of the Atlantic region in Canada, and inhabited the coastal areas of Gaspé and the Maritime Provinces east of the Saint John River. This traditional territory is known as Mi’gma’gi (Mi’kma’ki) and is made up of seven districts: Unama’gi (Unama’kik), Esge’gewa’gi (Eskikewa’kik), Sugapune’gati (Sipekni’katik), Epegwitg aq Pigtug (Epekwitk aq Piktuk), Gespugwi’tg (Kespukwitk), Signigtewa’gi (Siknikt) and Gespe’gewa’gi (Kespek). Mi’kmaq people have occupied their traditional territory, Mi’gma’gi, since time immemorial. Mi’kmaq continue to occupy this area as well as settlements in Newfoundland and New England, especially Boston. Oral history and archeological evidence place the Mi’kmaq in Mi’gma’gi for more than 10,000 years. (See also Indigenous Territory).

Traditional Life

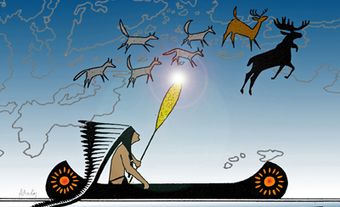

In the pre-contact world of Mi’gma’gi, oral and archeological history tells of seasonally patterned habitation and resource harvesting — spring and summer spent on the coast, fall and winter inland. The people of Mi’gma’gi relied on the variety of resources available, using everything from shellfish to sea mammals to land mammals small and large for nutrition, clothing, dwellings and tools. They also used the bountiful timber of the region to construct canoes, snowshoes and shelters, usually in combination with animal skins and sinews. The Mi’kmaq relied wholly on their surroundings for survival, and thus developed strong reverence for the environment that sustained them.

Population

Mi’gma’gi is home to 30 Mi’kmaq nations, 29 of which are located in Canada — the Aroostook Micmac Band of Presque Isle, Maine, has more than 1,200 members. All but two communities (the Qalipu Mi’kmaq First Nation and La Nation Micmac de Gespeg in Fontenelle, Québec) possess reserve lands. Many Mi’kmaq people live off-reserve, either in Mi’gma’gi or elsewhere. More still may not be included by registered population counts, as they are not recognized as status Indians under the Indian Act.

Social and Political Organization

Historically, Mi’kmaq settlements were characterized by individual or joint households scattered about a bay or along a river. Communities were related by alliance and kinship. Leadership, based on prestige rather than power, was largely concerned with effective management of the fishing and hunting economy.

Mi’kmaq share close ties with other local peoples, including the Maliseet and Passamaquoddy. With the Maliseet, Passamaquoddy, Penobscot and Abenaki peoples, the Mi’kmaq make up the Wabanaki Confederacy, a confederation of nations politically active at least from contact with Europeans to the present.

The Mi’kmaq Grand Council (Sante’ Mawio’mi) is the traditional government of the Mi’kmaq peoples, established before the arrival of Europeans. The council survives to this day, although its political powers have been restricted by federal legislation, such as the Indian Act. In the 1600s and 1700s, the council discussed political issues and entered into treaties with the British. Today, the Mi’kmaq Grand Council members advocate for the promotion and preservation of Mi’kmaq people, language and culture.

Representatives from across Mi’kmaq territory sit on the council. In the past, the Grand Chief (Kji Sagamaw or Kji Saqmaw) was the head of state for the collective Mi’kmaq political body, which consisted of captains (keptins or kji’keptan), who led the council, wampum readers (putu’s or putus), who maintained treaty and traditional laws, and soldiers (smagn’is), who protected the people. Today, the chief, captains and wampum readers still run the council, though their roles have been curtailed by the federal government to focus primarily on Mi’kmaq spirituality and culture. Other organizations, like the Mi’kmaq Rights Initiative (Kwilmu’kw Maw-klusuaqn), advocate politically for the recognition and implementation of treaty rights. (See also Treaties with Indigenous Peoples in Canada).

Culture

Like other Indigenous peoples in the Eastern Woodlands region, Mi’kmaq practised art intrinsically linked to the natural world. Contemporary Mi’kmaq artists like Alan Syliboy have reinterpreted Mi’kmaq artistic traditions, like rock painting and ornate quillwork clothing. (See also Indigenous Art in Canada).

Music is another important element of Mi’kmaq culture. Many traditional songs and chants are still sung during spiritual rituals, feasts, mawiomi (gatherings), cultural ceremonies and powwows. In some cases, Mi’kmaq chants consisted of vocables (spoken syllables) as a means of expressing emotion, rather than words with meanings.

Did You Know?

In April 2019, a video of Cape Breton Mi’kmaq teenager Emma Stevens singing “Blackbird” in Mi’kmaq went viral. The cover of the Beatles’ classic was produced by Emma’s teacher Carter Chiasson, translated by teacher Katani Julian and her father, Albert “Golydada” Julian, and recorded by Emma and fellow students at Allison Bernard Memorial High School in Eskasoni First Nation, Cape Breton. They translated the song into Mi’kmaq to bring awareness to the consequences of the endangerment of Indigenous languages during the UN’s International Year of Indigenous Languages, 2019. The video took off around the world, receiving high praise from public figures, including the original songwriter, Sir Paul McCartney, as well as a tweet from the prime minister of Canada, Justin Trudeau.

Language

Mi’kmaq is among the Wabanaki cluster of Eastern Algonquian languages, which include the various Abenaki dialects, and the Penobscot and Maliseet-Passamaquoddy languages. According to the 2021 census, 9,000 people are listed as speaking Mi’kmaw. (See also Indigenous Languages in Canada).

Mi’kmaq is written alphabetically. It has single- and double-letter constants as well as five vowels that make both long and short sounds. Mi’kmaq has a history of pictographs being used, but this writing system was modified by missionaries learning the language to teach Catholicism in the 1600s. Mi’kmaq had as many as 17 different dialects, including the unique Québec dialect Restigouche, but linguistic contact with French and English speakers has eroded the prevalence of the language and smoothed dialectical differences.

Despite challenges, language programs, including high school immersion programs, have helped to revitalize the language. In 1970, there were approximately 6,000 Mi’kmaq speakers, compared to the 9,000 reported in 2021. However, these numbers may be misleading. While the National Household Survey asks speakers to self-report “an understanding” of a language, linguists measure health of a language by the number of fluent speakers. In 1999, a report by the Nova Scotia Mi’kmaw Language Centre of Excellence indicated fewer than 3,000 fluent speakers.

Nevertheless, Mi’kmaq is the only Indigenous language in significant active use in Mi’gma’gi (Maliseet had less than 800 speakers in 2011), and as such, is an important symbol of cultural strength and perseverance for the community.

On 7 April 2022, the Government of Nova Scotia introduced the Mi'kmaw Language Act. This legislation enshrines the Mi'kmaq language as the province’s first language. It also supports efforts to protect and revitalize the language. The Act is seen as a step toward reconciliation.

Religion and Spirituality

Mi’kmaq spirituality is influenced by and closely connected to the natural world. The Mi’kmaq believe that living a good, balanced life means respecting and protecting the environment and living in harmony with the people and creatures that live on the earth. Analysis of the Mi’kmaq language enhances the fundamental importance of this worldview. Rather than a sequential, time-based verb tense structure (as in English), the Mi’kmaq language is experiential, relying on the evidence of the speaker to convey meaning.

Mi’kmaq culture and traditional religion is based on legendary figures like Glooscap (also written Kluscap) who is said to have formed the Annapolis Valley by sleeping on the land and using Prince Edward Island as his pillow. The Great Spirit is the creator of the world and all its inhabitants, a concept that was not destroyed when Catholic settlers and missionaries began to influence Mi’kmaq spirituality and religion in the 17th century. (See also Religion and Spirituality of Indigenous Peoples in Canada).

Origin Stories

The Mi’kmaq, like most Indigenous groups, use stories to tell about the past and about their spirituality. Mi’kmaq oral tradition explains that the world was created in seven stages. The Creator made the sky, the sun, Mother Earth and then the first humans: Glooscap and his grandmother, nephew and mother. From sparks of fire that Glooscap commanded to come forth, came seven men and seven women — the founding families of the seven Mi’gma’gi districts. There are many other origin stories that describe how things came to be and how to live a good life.

Vistas: Little Thunder, Nance Ackerman & Alan Syliboy, National Film Board of Canada

Christianity

In 1610, Henri Membertou, a Mi’kmaq chief (sagamo or sagamore), became the first Indigenous person to be baptized as a Catholic in New France, beginning a pattern of intense conversion and intermingling of customs. Mi’kmaq peoples, who had readily adapted to European trade goods, were likewise receptive to religious practices.

It has been said that the Concordat of 1610 — a formal agreement between the Mi’kmaq and the Vatican marked by the creation of a treaty wampum — combined trade, treaty and religion in relations between the Mi’kmaq and the French. The Concordat allegedly made the Mi’kmaq Catholic subjects, and therefore legitimized trade and other relations between settlers and Indigenous peoples in Acadia or Mi’gma’gi. However, historians and elders dispute this claim.

While some Mi’kmaq are Christian, traditional Mi’kmaq spirituality is still practised. There is a concerted effort on the part of Mi’kmaq people to protect and promote their religious beliefs and customs.

Colonial History

Due to their proximity to the Atlantic, the Mi’kmaq were among the first peoples in North America to interact with European explorers, fishermen and traders. As a result, they quickly suffered depopulation and socio-cultural disruption. Some historians estimate that European diseases (See Epidemic) resulted in a loss of up to half the Mi’kmaq population from about 1500 to 1600.

As a result of sporadic contact and trade with European fishermen, the Mi’kmaq who encountered the first sustained European settlements in what is now Canada were familiar with the people, their goods and their trade habits. Additionally, Mi’kmaq oral history tells of a Mi’kmaq woman’s ancient premonition that people would arrive in Mi’gma’gi on floating islands, and a legendary spirit who travelled across the ocean to find “blue-eyed people.” The foretelling of the arrival of Europeans meant Mi’kmaq were prepared when they first encountered fishermen off their shores.

Mi’kmaq participated in the fur trade by serving as intermediaries between Europeans and groups farther west, as fur-bearing animals quickly became scarce in the face of high demand. This fundamentally altered the lifestyle of the Mi’kmaq, who focused on trapping and trading furs rather than subsistence hunting and gathering.

Treaties

Prolonged conflict between French and British colonial powers often pulled Mi’kmaq into the fray. The Mi’kmaq were largely allied with French colonial forces, which had established settlements across Acadia until the 18th century. During that time, and after conflicts with Britain, the Mi’kmaq signed treaties in 1726, 1749, 1752 and 1760–61, followed by two treaties to secure alliances during the American Revolution. These were known as the Peace and Friendship Treaties. The 1726 treaty was the foundation for the subsequent treaties. (See also Indigenous Peoples: Treaties).

These treaties between sovereign nations recognize the inherent Indigenous rights of the Mi’kmaq, and form the basis for modern treaty claims and renegotiations. The Royal Proclamation of 1763, though it established Indigenous rights in much of Canada, did not mention Maritime colonies. For this reason, most post-treaty European and Loyalist settlers ignored, or were ignorant of, Mi’kmaq rights.

In 1985, the Supreme Court of Canada confirmed that the Mi’kmaq and the Crown have a historic relation stemming from the treaties of the 1700s, and that the Mi’kmaq have Indigenous rights to the lands described in those treaties. Ever since 1 October 1986, Treaty Day in Nova Scotia and some other parts of Atlantic Canada has commemorated the signing and significance of the Peace and Friendship Treaties.

19th and 20th Century Struggles

Life under British, and later Canadian, governance was not kind to the Mi’kmaq, who were subjected to conscious attempts to alter their lifestyle. Most moves to establish them as agriculturalists failed because of badly conceived programs and encroachments upon reserve lands. Economic patterns that privileged employment as labourers effected irreversible change: crafts, coopering, the porpoise fishery, and road, rail and lumber work integrated the Mi’kmaq into the 19th- and 20th-century economy, but left them socially isolated.

As with many Indigenous peoples in Canada, the Mi’kmaq are strongly affected by the lasting trauma of residential schools. Adding to this cultural, generational and economic dislocation, in the 1940s, the Department of Indian Affairs forced more than 2,000 Mi’kmaq people living in numerous small communities to relocate to government-designated reserves. The moves, undertaken for the sole purpose of streamlining government administration were fraught with mismanagement and experimental tactics, and had disastrous effects on the communities. Homes, churches and industries were abandoned and replaced with poor conditions and economic dependency.

Did you know?

Despite facing discrimination in Canada and a lack of civil rights (Mi’kmaq and other Indigenous peoples were not granted the right to vote until 1960), more than 200 Mi’kmaq warrior-soldiers ( sma’knisk) served with the Canadian Expeditionary Force (CEF) in the First World War. Many were wounded or killed in battle (see Indigenous Peoples and the First World War). In addition, Mi’kmaq soldier Corporal Samuel Glode (Gloade) was highly decorated for bravery on the Western Front. Glode was awarded the Distinguished Conduct Medal (DCM) for disarming 450 land mines and bombs in 1918, saving many Canadian lives.

Contemporary Life and Activism

As of January 2024, there were 13 Mi’kmaq nations in Nova Scotia with a total registered population of 19,157. New Brunswick’s nine nations included 9,107 registered people, while the two nations in each of Prince Edward Island and Newfoundland and Labrador had populations of 1,503 and 28,602, respectively. The three Québec nations had a total population of 7,837. Before 2011, the population of registered Mi’kmaq people in Newfoundland and Labrador was significantly lower; in that year, the federal government recognized the status of more than 23,000 Mi’kmaq people, who formed the Qalipu Mi’kmaq First Nation.

The formation of the Qalipu is one example of continued activism among Mi’kmaq people. In 1999, the Supreme Court of Canada affirmed the rights of Donald Marshall, Jr., and thus all Mi’kmaq peoples, to a “moderate livelihood” through hunting and fishing rights. Marshall had been convicted in 1996 of fishing out of season, but the court ruled that the Peace and Friendship Treaties, signed in 1760 and 1761, guaranteed Mi’kmaq these rights.

The decision sparked what is known as the Burnt Church Crisis, where tensions reached a boiling point between Mi’kmaq and non-Indigenous fishermen, who argued that unchecked harvesting in the lobster fishery would lead to devastation of stocks. Despite the pacifist lobbying of organizations like the Bay of Fundy Inshore Fishermen’s Association among their own members, some non-Indigenous fishermen destroyed Mi’kmaq traps and other equipment. The situation threatened to devolve into violence. The federal government brought the crisis to somewhat of a close by buying licences and equipment from some non-Indigenous fishermen and entering into agreements with several Mi’kmaq communities to regulate a commercial fishery. Other Mi’kmaq communities did not reach agreements and continue to petition the federal government to recognize treaty rights.

Ongoing tensions over lobster fishing between non-Indigenous and Sipekne’katik (Mi’kmaq) fishers escalated in October 2020. A lobster pound was burned down in Middle West Pubnico the night of 17 October. The Mi’kmaq have called on the federal government, which is responsible for fisheries, to provide clear guidance on what a “moderate livelihood” involves.

In October 2013, members of the Elsipogtog First Nation in New Brunswick organized a demonstration against natural gas fracking being conducted on Crown land near their community. The protests centred on environmental arguments against fracking and the unceded nature of the territory in question. Protesters erected blockades on Highway 11 and several organizers were arrested. Non-violent protesters faced off against RCMP officers, producing iconic images and reigniting debate over the scope of Aboriginal title and the politics of environmental stewardship within an industrial economy.

Share on Facebook

Share on Facebook Share on X

Share on X Share by Email

Share by Email Share on Google Classroom

Share on Google Classroom