John Collins’ Purchase of 1785 is one of the oldest land agreements between Indigenous peoples and British authorities in Upper Canada (later Ontario). It concerned the use of lands extending from the northwestern end of Lake Simcoe to Matchedash Bay, an inlet off Georgian Bay in Lake Huron. The purpose was to provide the British with a protected inland water route between Lake Ontario and Lake Huron, away from potential American interference. This passage was necessary for trade and the resupply of British western outposts. John Collins’ Purchase is one of many agreements made during the late 18th and early 19th centuries, known as the Upper Canada Land Surrenders.

Historical Context

Prior to the negotiations, the Crawford Purchase of 1783 had resulted in the transfer of a large area of First Nations land to the British for settlement by Loyalists displaced by the American Revolutionary War. The ceded territory ran along the north shores of Lake Ontario and the St. Lawrence River between present-day Brockville and the Trent River.

Among the possible routes were two that began on the north shore of Lake Ontario. One followed the Trent River from the Bay of Quinte to Rice Lake, then to Lake Simcoe. The other started at York and followed the Humber and Holland rivers to Lake Simcoe. From there, both routes followed the Severn River to Georgian Bay.

The British (and the French before them) had been using these water routes for several years. Originally, they were entirely within Mississauga and Chippewa lands, but the Crawford Purchase had secured the first part of the Trent River Route from the Mississauga for the British. That left the largest portion of the route to be negotiated with the First Nations.

In 1785, Quebec Lieutenant-Governor Henry Hamilton sent Deputy Surveyor General John Collins to survey the Toronto Carrying Place route. He was also to report on what lands it might be necessary to purchase from their Indigenous inhabitants. Although little evidence survives of Collins’ journey, it seems that he succeeded in negotiating an agreement for a right-of-way through some of the land in question.

Negotiations

Collins’ report stated that the agreement allowed the Crown to make roads through Indigenous territory between Lake Simcoe and Matchedash Bay. Surprisingly, he also noted that no payment had been made for this agreement, nor had one been requested. He added that the chiefs stated their people were poor and naked and wanted clothing but would let “their good Father” (King George III) decide what the quantity should be.

Interpreter Jean-Baptiste Rousseau was a member of Collins’ expedition. In 1795, he recalled that Captain William Crawford, who had negotiated the Crawford Purchase of 1783, and he were with Collins when they met with the Mississauga and Chippewa in August 1785. Rousseau stated that the meeting resulted in the negotiation of a right-of-way agreement of “one mile (1.6 km) on each side of the foot path from the Narrows at Lake Simcoe to Matchidash Bay, with three Miles and a half (5.6 km) Square, at each end of the said Road.” The larger blocks of land were intended for storage and transportation infrastructure. Rousseau also maintained that a mile-wide strip stretching along both sides of the Severn River was part of the agreement.

Outcome

Unfortunately, no formal documents exist of this agreement and surviving descriptions of the territory supposedly included in the transfer are contradictory. An agreement for a land transfer in 1815, which involves the Collins purchase, implies a much larger piece of territory than Rousseau recalled. Additionally, his recollections of the agreement do not accord with any existing maps of the purchase, nor do later investigations mention any 1785 agreement.

In September 1786, Superintendent of Indian Affairs Sir John Johnson met with First Nations representatives at the Bay of Quinte to propose a cession of lands along the Toronto Carrying Place and north via Lake Simcoe to Matchedash Bay. One year later, he met there again with Indigenous leaders and concluded a formal cession of land on the central north shore of Lake Ontario with the distribution of goods. Unfortunately, only an incomplete document known as the “Blank Deed” exists to confirm this agreement, which allegedly included the purchase of lands at Matchedash Bay.

In August 1788, Major John Butler met with various representatives of the Mississauga and Chippewa to confirm the previous year’s discussions of the Toronto and Matchedash purchases. As well, the territory along the central north shore of Lake Ontario covered by the Johnson-Butler Purchase (also known as the Gunshot Treaty) was included. Although additional goods were distributed, no deeds or maps have survived. The Toronto Purchase was confirmed in 1805 and was considered as confirmation of the 1787 Blank Deed, although no specific mention was made of the Collins or Johnson-Butler purchases.

Controversy

The boundaries of Collins’ Purchase were not confirmed by colonial officials at the time. Although the agreement is usually dated 1785, it is highly likely that it was transacted in 1787 and not confirmed until 1795–98. Existing evidence indicates that Collins negotiated a right-of-way with Mississauga and Chippewa First Nations in 1785 and the Matchedash tract was purchased in 1787. Later maps show a large rectangular piece of land, which is not in accordance with Rousseau’s recollections of a much narrower tract.

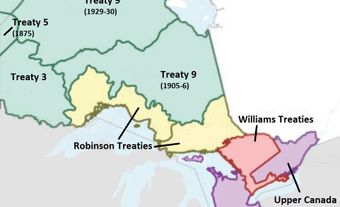

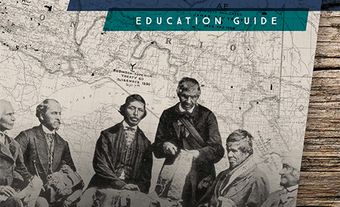

In the 1790s and early 1800s, British officials found few records to confirm the extent and conditions governing the purchase. Later historical analyses are based on the documented memories of First Nations members and government officials long after the purchase. The lack of any valid documentation was raised as an issue by Chippewa and Mississauga representatives at the Williams Commission hearings in 1923. As a result, the larger boundaries were incorporated within those covered by the Williams Treaties of 1923. These treaties also surrendered hunting and fishing rights in off-reserve lands. In compensation, each Mississauga and Chippewa band member received a one-time payment of $25. Additionally, the Mississauga received $233,425, while the Chippewa received $233,375 as one-time payments.

Later Settlement

In 1992, the seven Williams Treaties First Nations filed a lawsuit against the federal government asking for financial compensation for the land surrenders and loss of rights dictated by the Williams Treaties. Ten years later, a trial began in which Canada and Ontario acknowledged limited off-reserve treaty harvesting rights. After discussion, litigation was dropped in favour of out-of-court negotiations. These began in March 2017 between Canada, Ontario and the First Nations involved. A negotiated settlement was approved by First Nations representatives in June 2018, signed by them in July and by Canada and Ontario in August.

The agreement on this longstanding dispute was announced on 13 September 2018 at a ceremony attended by representatives of the First Nations, the Government of Canada and the Government of Ontario. In November of 2018, Canadian Minister of Crown-Indigenous Relations, Carolyn Bennett, and Minister of Indigenous Affairs for Ontario, Greg Rickford, apologized for the negative impacts of the Williams Treaties on the people of the First Nations affected by the treaties.

In addition, the agreement gave $1.11 billion to the First Nations involved ($666 million from Canada and $444 million from Ontario), recognized their harvesting rights and allowed each First Nation to add up to 4, 452 hectares to their reserves by purchase from willing sellers. Speaking for the seven Williams Treaties First Nations, Chief Kelly LaRocca noted the settlement agreement marked “the beginning of healing for our people,” as well as the “renewal of our Treaty relationship with one another.”

Share on Facebook

Share on Facebook Share on X

Share on X Share by Email

Share by Email Share on Google Classroom

Share on Google Classroom