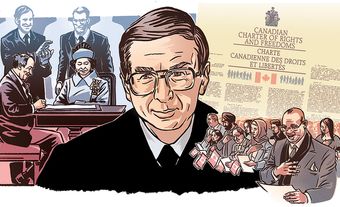

John Sopinka, Supreme Court justice, lawyer, social advocate, author, football player, violinist (born 19 March 1933 in Broderick, SK; died 24 November 1997 in Ottawa, ON). John Sopinka played in the Canadian Football League while studying law at the University of Toronto. As a prominent litigation attorney, he represented Ukrainian Canadians in national and international commissions and handled other influential cases. In 1988, he became the first Ukrainian Canadian appointed to the Supreme Court of Canada.

Early Life

John Sopinka was born in Broderick, a small village south of Saskatoon. His parents, Metro Sopinka and Nancy Kikcio, were ethnic Ukrainian farmers who had emigrated from Poland in 1926. Sopinka and his five siblings spoke the Ukrainian Lemko dialect at home. The family moved to the Stoney Creek area of Hamilton, Ontario, when Sopinka was seven years old. His father became a steelworker.

An accomplished violinist, Sopinka was playing with the Hamilton Philharmonic Orchestra by age 15. He graduated from Saltfleet High School in Stoney Creek and, in 1955, graduated summa cum laude with a Bachelor of Arts from the University of Toronto. Sopinka also played halfback on the Varsity Blues football team that won the 1954 Canadian Intercollegiate Athletic Union championship.

In 1957, Sopinka married fellow law student Marie Wilson. They had two children, Melanie and Randall.

CFL Career

While studying law at the University of Toronto, Sopinka played with the Toronto Argonauts of the Canadian Football League (CFL) in 1955 and 1956. He started the 1957 season with the Montreal Alouettes before returning to the Argonauts. In his CFL career, Sopinka caught eight passes for 116 yards, made six interceptions and 15 punt returns and scored one touchdown.

The Law and Social Advocacy

Sopinka was called to the Ontario bar in 1960. He would later be called to the bar in Newfoundland, New Brunswick, Saskatchewan, Alberta, Yukon and Northwest Territories.

Sopinka began his law career in Toronto with Fasken & Calvin. He then became a senior partner with Stikeman, Elliott. An effective litigator, he also lectured at the University of Toronto and Osgoode Hall Law School. Sopinka wrote The Trial of an Action (1981), which remains a respected source for insights on the topic of trial techniques.

Among his many high-profile clients was Susan Nelles, a nurse who was charged in 1981 for the deaths of four babies at Toronto’s Hospital for Sick Children. The charges were dropped in 1982. Judge Samuel Grange led a Royal Commission that investigated the case. Representing Nelles, Sopinka proved that the police and Crown had engaged in malicious prosecution. Nelles was awarded financial settlements. The case was eventually heard by the Supreme Court. Its ruling ensured that police, Cabinet ministers and prosecutors are held responsible for malicious prosecution.

Beginning in 1985, Justice Jules Deschênes led the Commission of Inquiry on War Criminals. Its purpose was to determine the presence of Nazi war criminals in Canada. The Ukrainian Canadian Civil Liberties Association created the Civil Liberties Commission, which hired Sopinka. Sopinka argued that accusations of Ukrainian Canadians harbouring Nazi war criminals were baseless. He succeeded in preventing them from being deported to the Soviet Union.

In 1988, the World Congress of Free Ukrainians convened the International Commission of Inquiry into the 1932–33 Famine in Ukraine, known as the Holodomor. Sopinka was co-counsel with Alexandra Chyczij and argued issues of international law, including whether the forced famine was genocide. The commission’s final report was submitted to the United Nations.

While Sopinka was serving on the commission, Prime Minister Brian Mulroney appointed him to the Supreme Court on 24 May 1988. When sworn in on 23 June 1988, Sopinka became the first Ukrainian Canadian justice on the Supreme Court, and the first in 10 years who had not first been a judge.

Supreme Court Justice

During his nine years on the Supreme Court, Sopinka wrote many important decisions. Among them was the 1991 R. v. Stinchcombe decision, in which the Supreme Court determined that the Crown must supply the defence council with all relevant information. While the Crown could still define relevance, the ruling ended the practice of prosecutors surprising defence councils with evidence during a trial. The decision is believed to have reduced the number of wrongful convictions in Canada.

Another important case involved Sue Rodriguez, who in 1991 was diagnosed with amyotrophic lateral sclerosis (ALS). She first asked the Supreme Court of British Columbia and then the Supreme Court of Canada to deem unconstitutional section 241(b) of the Criminal Code (a maximum 14-year prison term for aiding or abetting a suicide) so that a doctor could legally assist her in dying. Sopinka voted with the majority in a 5–4 ruling against Rodriguez. He wrote the majority opinion, arguing that section 241 (b) did not violate section 7 of the Charter of Rights and Freedoms, addressing security of the person, and so assisted suicide should remain illegal. A national debate ensued that eventually resulted in Carter v. Canada (2015). It overturned Rodriguez v. British Columbia and led to legislation permitting assisted suicide in 2016.

Sopinka believed that justices are public figures and should speak freely about their decisions, to increase people’s confidence in the court. He helped demystify the court by speaking openly with the media and in public addresses about how cases were decided. While serving on the Supreme Court, Sopinka also co-wrote The Law of Evidence in Canada (1992) with Alan W. Bryant and Sidney N. Lederman. The well-respected book remains widely read.

Death

Sopinka died on 24 November 1997, six weeks after being diagnosed with a rare blood disease. He was 64. His body lay in state in the grand entrance hall in the Supreme Court building. Among the more than 400 mourners were Prime Minister Jean Chrétien and Chief Justice Antonio Lamer. Lamer said that he and the other justices would miss Sopinka’s “blend of profound intelligence, infinite compassion and instinct for justice.”

Honours

Since 1999, the championship trophy at Canada’s national trial advocacy competition, where law students from across Canada compete against each other, has been called the Sopinka Cup. The provincial courthouse in Hamilton was also named the John Sopinka Courthouse in his honour in 1999.

(See also John Sopinka Obituary.)

Share on Facebook

Share on Facebook Share on X

Share on X Share by Email

Share by Email Share on Google Classroom

Share on Google Classroom