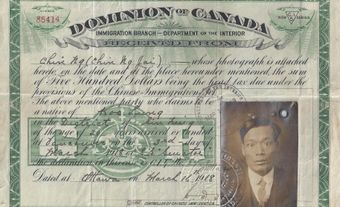

Kew Dock Yip (葉求鐸), community leader, lawyer, school trustee and film actor (born on 23 August 1906 in Vancouver, BC; died 2 July 2001 in Toronto, ON). Yip was the first lawyer of Chinese descent in Canada. (See Chinese Canadians.) He and fellow lawyer Irving Himel played a pivotal role in repealing the Chinese Immigration Act, 1923.

Early Life

Kew Dock Yip, known in the community as Dock Yip, was born in Vancouver in 1906. His father, Yip Sang, was a paymaster of the Canadian Pacific Railway and a prominent merchant. He was also the patriarch in Vancouver’s Chinatown, renowned for his community leadership and philanthropic work in health and education. He had four wives and 23 children.

Kew Dock Yip was educated at numerous universities. (See Universities in Canada.) In 1928, he enrolled at Columbia University. However, after one semester, he transferred to the University of Michigan. There, he graduated with a degree in pharmacology in 1931. He wanted to practice pharmacy in British Columbia. However, he was not allowed to enter the profession because “Orientals” did not have the right to vote. (See Racial Segregation of Asian Canadians.) Instead, he continued his studies at the University of British Columbia and earned a Bachelor of Arts in 1941. By then, he had worked eight years as a secretary at the Chinese consulate in Vancouver. He now turned his attention to a career in law. Yip and his future spouse, Victoria Chow, moved to Toronto, where there were no restrictions to hinder his ambitions to pursue a law profession. They married in 1942 and opened a restaurant with some business partners. The restaurant provided food and work for Yip and his wife. It also gave Yip enough time to study law.

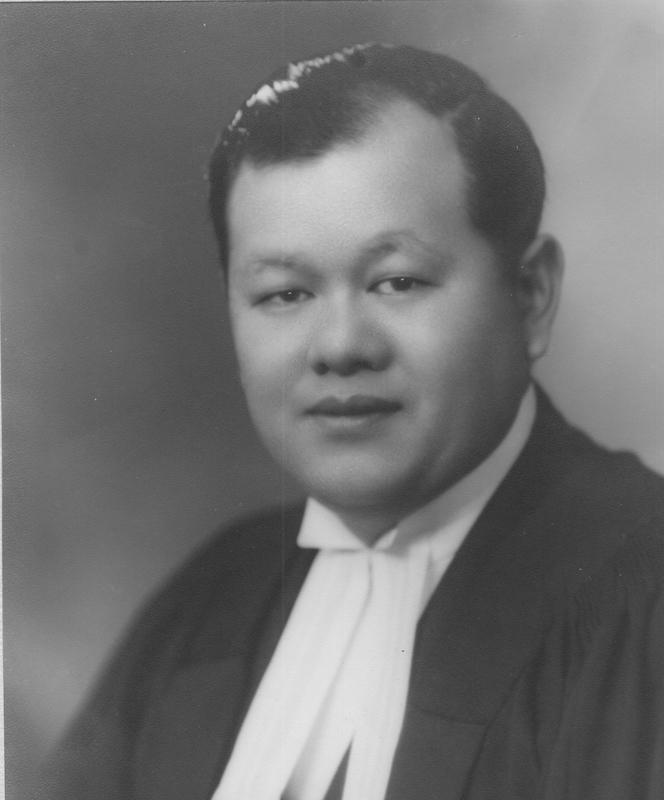

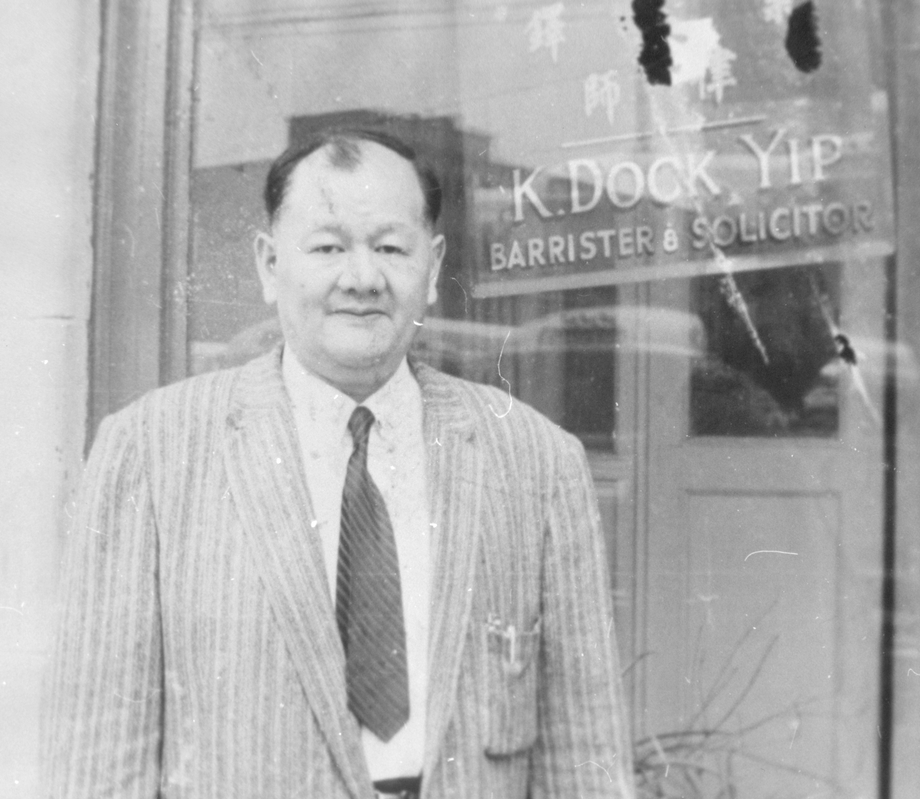

He applied three times before being admitted into Osgoode Hall Law School. Yip finally graduated in 1945 with a Bachelor of Law. He was the first Canadian of Chinese descent ( see Chinese Canadians) to be called to the bar in Canada. He opened a law office on Elizabeth Street, later at Bay and Dundas streets, in Toronto’s first Chinatown.

Immigration Reform

During the Second World War, Canada initially restricted Chinese people from joining the military. (See also History of the Armed Forces in Canada.) However, in 1942, Dock Yip managed to enlist as an army reservist with The Queen's Own Rifles of Canada. (See Canadian Army.) During training, he shared a tent with Irving Himel, with whom he became close friends. Both Dock Yip and Himel experienced discrimination: Yip as a Chinese person and Himel as a Jew. (See Chinese Canadians; Jewish Canadians.) Eventually, they became committed to fighting injustices as fellow lawyers. This united them in the goal of repealing the Chinese Immigration Act, known also as the Chinese Exclusion Act. From 1923 onward, virtually all Chinese were barred from entering Canada. Yip was just a teenager when the exclusionary law was passed.

In 1923 I attended some Chinese mass meetings against the Exclusion Act. Joseph Hope — Ying Hope’s older brother, a businessman — tried to oppose it but he couldn’t do anything. My brother was studying medicine at Queen’s University. He went to Ottawa to protest. He couldn’t do anything either. He was in the gallery at the House of Commons and just watched as they passed the Act. I was at a meeting where Joseph Hope spoke after they passed the Act. We called it humiliation day, July 1st, 1923. I listened to him. Maybe that inspired me to help change the Act when I finished law.

— Dock Yip

In 1946, Yip and Himel worked together with like-minded civil liberties and human rights activists from across the country. By November, the Committee for the Repeal of the Chinese Immigration Act was established under their leadership. They were joined by 69 Chinese and non-Chinese members from labour, political and religious organizations. Together, they successfully lobbied and brought about the repeal of the exclusionary law in 1947.

Yip’s advocacy for his community continued. He lobbied the government until 1966 to lower the entrance barriers for Chinese immigrants and to ease family reunification. (See Immigration to Canada; Immigration Policy in Canada.)

Life Beyond Law

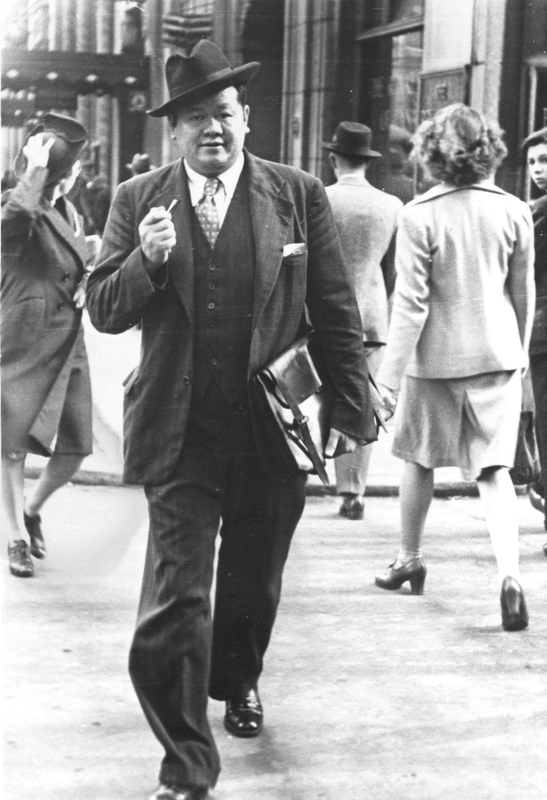

Dock Yip was fluent in Chinese (Taishanese, Cantonese and Mandarin). He served his clients at his Chinatown office for 47 years. Early on, many came to him because he was initially the only Chinese-speaking lawyer in Toronto.

I’m not a lazy man. All my life I’m busy — work, work, work. If I stop working I’ll die. I warn you. Don’t ever stop. Get another occupation rather than retiring.

— Dock Yip

In the 1970s, Yip served two terms as a school trustee on Toronto’s Board of Education. In 1985, at age 79, he turned to acting. He had roles in the movies Year of the Dragon, Diamonds (1987) and Fearless Tiger (1991). In 1988, he appeared in a Cyndi Lauper rock video. He retired from his law practice in 1992.

Honours and Awards

Dock Yip, along with some of his brothers, were members of the Chinese Students Soccer Team that made history in 1933 by winning the Mainland Cup — the championship for soccer clubs in British Columbia. The team is believed to have been the only soccer team composed of Chinese players outside of China. The players competed at a time when Chinese people across Canada faced severe racism. In British Columbia, there were over 100 anti-Chinese policies and laws. (See Racial Segregation of Asian Canadians.) In 2011, team members, many who went on to remarkable success, including midfielder Yip, were inducted into the BC Sports Hall of Fame.

Yip received many awards from a number of Chinese Canadian organizations. Ryerson University recognized him for being the oldest student in its continuing education program. Although he was already known for his wide knowledge and diverse interests, he enrolled to study Shakespearean English there in 1994 at the age of 87.

Yip’s fellow lawyers highly respected him as a role model and person of integrity. In 1998, he was awarded the Law Society Medal by the Law Society of Upper Canada for outstanding service to the legal profession.

He died in Toronto on 2 July 2001 at the age of 94. He was survived by his wife, three sons and five grandchildren.

Share on Facebook

Share on Facebook Share on X

Share on X Share by Email

Share by Email Share on Google Classroom

Share on Google Classroom