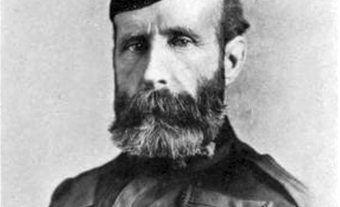

Albert Johnson, also known as the “Mad Trapper,” outlaw (born circa 1890–1900, place of birth unknown; died 17 February 1932 in Yukon). On 31 December 1931, an RCMP constable investigating a complaint about traplines was shot and seriously wounded by a trapper living west of Fort McPherson, NT. The ensuing manhunt — one of the largest in Canadian history — lasted 48 days and covered 240 km in temperatures averaging -40°C. Before it was over, a second policeman was badly wounded and another killed. The killer, tentatively but never positively identified as Albert Johnson, was so skilled at survival that the police had to employ bush pilot Wilfrid “Wop” May to track him. The Trapper’s extraordinary flight from the police across sub-Arctic terrain in the dead of winter captured the attention of the nation and earned him the title “The Mad Trapper of Rat River.” No motive for Johnson’s crimes has ever been established, and his identity remains a mystery.

This article contains sensitive material that may not be suitable for all audiences.

Standoff at Rat River

On 7 July 1931, trappers William and Edward Snowshoes encountered a stranger they mistakenly called Albert Johnson at a camp on the Peel River near Fort McPherson, Northwest Territories. It was the name by which he would be known thereafter. On 21 July, when Johnson was in Fort McPherson to purchase supplies, RCMP Constable Edgar Millen briefly questioned him about his activities. Although Johnson was said little and avoided giving direct answers, Millen only advised him to buy a trapper’s licence and then let him go on his way.

DID YOU KNOW?

Trapping animals for fur is carried out in almost every country of the world. In Canada, trapping is done mostly for animal pelts, though some people trap for food. Fur trapping is a foundational practice in both Indigenous and European cultures in Canada and was a primary reason for colonial settlement (see also Fur Trade).

Johnson moved to the trapping grounds of the Rat River and built a small log cabin there. On 25 December, local First Nations trappers complained to the RCMP at the Arctic Red River post that Johnson had been interfering with their traplines. On 28 December, Constable Alfred King and Special Constable Joe Bernard arrived at Johnson’s cabin to question him. Johnson refused to open the door or even speak to King, who then had to travel 128 km to Aklavik to obtain a search warrant.

King and Bernard returned to Johnson’s cabin on 31 December, along with Constable R.D. McDowell and Special Constable Lazarus Sittichinli. King knocked, and Johnson fired a shot that pierced the door and struck King in the chest. The other officers exchanged gunfire with Johnson and then put King on a dogsled for a desperate race to the hospital in Aklavik.

King survived, but the police were astounded that Johnson would shoot an officer over a minor issue like a trapping violation. Realizing that Johnson was an extremely dangerous individual, RCMP Inspector Alexander Eames personally led a police posse to arrest Johnson. In Eames’s party were Constables Millen and McDowell; Special Constables Bernard and Sittichinli; Knute Lang, Ernest Sutherland and Karl Gardlund; and First Nations guide Charlie Rat.

The police party reached Johnson’s cabin on 9 January 1932. Johnson, who had fortified the cabin, responded to Eames’s demand to surrender with gunfire. Armed with a rifle and a shotgun, Johnson drove back repeated attempts to storm the cabin. On 10 January, the police used dynamite, blowing off the cabin’s roof and partially collapsing its walls. Amazingly, Johnson was unhurt and continued to fire at the police. With the temperature at -43°C and food for men and dogs running low, Eames had to withdraw to Aklavik. Millen and Gardlund returned to the cabin on 14 January and found that Johnson had fled. Snowfall had covered his tracks.

Outlaw Hero

Johnson’s one-man stand against the police had drawn the attention of the media, which labelled him “The Mad Trapper of Rat River.” A public mired in the depths of the Great Depression sympathized with the fugitive. Eames stated that Johnson was not a “demented trapper” but “a shrewd and resolute man… a tough and desperate character.” As the northern drama unfolded, the public eagerly awaited the latest developments.

Fatal Encounter

Police faced the prospect of searching for Johnson in a 260 km2 area between the Mackenzie River in the east and the Richardson Mountains in the west. Eames’s second posse included Sutherland, Sittichinli, Noel Verville, sergeants Earl Hersey and R.F. Riddell of the Royal Canadian Corps of Signals, and 11 First Nations trackers. They joined Constable Edgar Millen and Gardlund at the Rat River.

By 21 January, the searchers had still not found Johnson’s trail, and supplies were again running low. Eames left Millen, Gardlund, Verville and Riddell to continue the hunt while he and the others returned to Aklavik. Millen got a break when a First Nations hunter reported he’d heard a rifle shot in the Bear River vicinity. Guessing that it might have been Johnson shooting game, Millen led his party in that direction.

On 30 January, the police party caught up to Johnson. Millen called on him to surrender, and Johnson opened fire with a rifle. In the ensuing gunfight, Johnson killed Millen with a shot through the heart. The surviving members of the posse thought they had Johnson trapped, but he escaped under cover of darkness by climbing an almost vertical cliff.

DID YOU KNOW?

A cairn commemorating Constable Edgar Millen’s death is a Territorial Historic Site in the Northwest Territories.

Wilderness Fugitive

Johnson had already proven himself to be a resourceful woodsman with remarkable stamina. He confounded his pursuers with tricks like backtracking and leaving blind trails. Where possible, he followed caribou trails, an effective way of disguising his own tracks. He found his way through underbrush that seemed impenetrable. Johnson had to stop to snare small game for food, and in the extreme cold he could risk building only small fires under the cover of snowbanks. He travelled in weather that kept even experienced First Nations hunters in their camps and used the terrain to his advantage at every opportunity. As one veteran trapper put it, “It is rough enough just staying alive under those conditions let alone having to be on the run.”

Air Support

Eames requested the use of an airplane to help track Johnson. It would be the first time the RCMP used aircraft in a manhunt. On 5 February, renowned bush pilot Wilfred “Wop” May landed in Aklavik in a Bellanca monoplane. May’s participation was vital as he ferried men and supplies to strategic locations and searched for Johnson’s trail from the air. His work spared the men on the ground the gruelling task of following Johnson’s blind trails. On 9 February, a blizzard grounded May’s plane and kept ground patrols in their camps. Three days later, the police received the astonishing report that under harrowing conditions Johnson had crossed the Richardson Mountains.

DID YOU KNOW?

Wilfrid Reid (“Wop”) May was a First World War flying ace who was part of the dogfight in which the infamous Red Baron was gunned down. After the war, he was a renowned barnstormer (or stunt pilot) and bush pilot, flying small aircraft into remote areas in Northern Canada, often on daring missions. May flew in several historic flights, carrying medicine and aide to northern locations and assisting law enforcement in manhunts.

Final Confrontation

On 14 February, Wop May sighted Johnson’s trail where the Eagle and Bell rivers join. Fog kept May on the ground for the next two days, but Eames led a party of 11 men, including Gardlund, Sittichinli, Riddell and Hersey, up the Eagle River, leaving directional markers on the ground for May. On 17 February, May was airborne again and was overhead when the police overtook Johnson on a hairpin bend of the frozen river.

At first Johnson tried to run but then threw himself down in the snow and opened fire, using his backpack for cover. He disregarded Eames’s shouts for him to give up. Johnson shot Hersey, though not fatally. Directed by signals from May, the posse spread out and caught Johnson in a crossfire. Johnson was hit several times, with one fatal bullet severing his spine.

Aftermath and Legacy

A postmortem was performed on Johnson’s body in Aklavik, and he was buried in the local cemetery. At the time of his death, Johnson possessed $2,410 in Canadian currency, $10 in American currency, five pearls of low value, and a small amount of gold that included pieces of dental work. No clue to his identification was found on his person or in his cabin. His fingerprints matched none in Canadian or American police files. Johnson’s real identity remains a mystery.

The “Mad Trapper” has been the subject of numerous films, books and articles, including a novella by Rudy Wiebe. Canadian author Dick North presented a strong case for Johnson

actually being an American fugitive named Arthur Nelson in his book Trackdown: The Search for the Mad Trapper (1989).

Johnson’s remains were exhumed by a forensic team and submitted for DNA analysis for the television documentary Hunt for the Mad Trapper, which aired in 2009. Results of the scientific testing suggest that Johnson was either American or Scandinavian and in his 30s when he was killed. The results put several claims and theories regarding Johnson’s identity to rest.

Share on Facebook

Share on Facebook Share on X

Share on X Share by Email

Share by Email Share on Google Classroom

Share on Google Classroom