During the First World War, military personnel from all combatant countries used millions of animals for work and as pets. This includes Canadians who served overseas as members of the Canadian Expeditionary Force (CEF) and the Canadian Siberian Expeditionary Force (CSEF), as well as Canadian service personnel based in Canada. Horses, mules, dogs and birds were the most common animals employed, although there were several others, including reindeer and glow-worms.

Historical Overview

Human beings have interacted closely with animals for about 2.6 million years and domesticated them for several reasons. These include food (meat, milk, eggs, honey), clothing (wool, leather, feathers), work (ploughing, hunting, guarding), transportation (riding, carrying, hauling), companionship (pets, mascots), entertainment (zoos, circuses, rodeos, bullfighting, films), sports (horse and dog racing) and pest control (rodents, snakes). Certain animals have also proven their value during conflict and warfare throughout history.

Horses have likely been used in combat since 1500 BCE, first to pull chariots and then to carry soldiers. Horses also carried or hauled military supplies, along with mules and donkeys. War elephants were first used in ancient India before being employed elsewhere. Dogs have assisted soldiers since at least 600 BC. They would charge into the enemy’s ranks to break up battle formations, followed by soldiers. Camels were first employed in warfare in ancient times. They carried warriors and supplies into battle.

Did you know?

One of the greatest military feats in history involved elephants. In 218 BC, Carthaginian general Hannibal used nearly 40 war elephants in crossing the Alps to attack Rome.

Work Animals

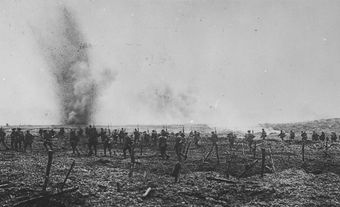

During the First World War, Canadians used horses to carry cavalry into battle and scouts on reconnaissance missions. They also towed artillery guns, while senior officers were entitled to a horse. By the end of the war, in November 1918, the CEF had used nearly 25,000 horses and mules on the Western Front. In addition to cavalry and artillery, they were also employed as pack animals to carry goods and haul wagons and ambulances. The Canadian Army Service Corps used horses and mules to deliver food, forage, ammunition, equipment and clothing, as well as engineer material and stores. In northern Russia, the CSEF used reindeer to haul troops and supplies across frozen tundra.

Did you know?

The PDSA Dickin Medal recognizes “outstanding acts of bravery or devotion to duty displayed by animals” during wartime and is known as the animals’ Victoria Cross. Because it was only instituted in 1943, it automatically excluded any animals from the First World War. In 2014, however, after a successful lobbying campaign, the war horse Warrior was chosen to represent the role that all animals played in the First World War and was awarded the only Honorary PDSA Dickin Medal to date. Warrior was the charger of Brigadier-General Jack Seely, the British commander of the Canadian Cavalry Brigade from its formation in January 1915 to May 1918.

Dogs were employed for several tasks. They carried written messages between units and laid telephone lines from spools on their backs that unrolled as they moved forward. Dogs also accompanied soldiers on patrol and performed sentry duty. They could smell poison gas deployed by the enemy before humans could. Dogs also located wounded soldiers on the battlefield while carrying medical backpacks and hunted rats in dugouts and trenches.

Different types of birds also had a role during the war. Carrier pigeons were the most common. With their unerring sense of direction, they were used to carry messages between front line units and headquarters. Canaries, along with mice, were particularly useful to detect poison gas in front line trenches and signal a growing lack of oxygen in tunnels. Slugs were also used to detect poison gas. They were more sensitive to mustard gas than humans and responded by compressing their bodies and closing their breathing holes; their reaction warned soldiers that gas was present. Another atypical war animal was the glow-worm. Glow-worms were collected, put in glass jars and used as a light source to read maps, messages and letters from home.

Did you know?

The Canadian Army Veterinary Corps (CAVC) was organized in 1914 based on the pre-war Army Veterinary Service (AVS). The CAVC’s main role was to treat horses; by the end of the war, it consisted of more than 800 personnel.

Animals as Pets and Mascots

Many soldiers kept pets on or near the front lines. Small dogs and cats were the most popular and helped soldiers deal with the harsh bleakness of life at the front. They were also very useful in keeping down the large numbers of rats and mice infesting the trenches. Other small animals, such as rabbits, rodents and birds, were also kept as pets.

“Winnie” was a female black bear cub bought by veterinarian lieutenant Harry Colebourn that accompanied him to England. When Colbourn went to France, he left the bear at the London Zoo. Winnie remained there after the war and became the inspiration for A.A. Milne’s Winnie-the-Pooh children’s stories.

Animals were also used as mascots for entire military units, whether based in Canada or overseas. Although dogs were most common, horses and goats were also popular.

Memorials to Animals in War

Canada has two national memorials in Ottawa that recognize the service of animals in wartime. The first was carved in 1927 over the doorway that leads to the Memorial Chamber in the Peace Tower, the central fixture of Canada’s Parliament Buildings. The carving depicts reindeer, mules, pigeons, horses, dogs, canaries and mice. An inscription in both official languages notes, “The tunneller’s friends, the humble beasts that served and died.”

In 2012, the Animals in War Dedication was unveiled in Confederation Park in Ottawa. It honours all the animals that served beside their human counterparts during wartime. The memorial consists of three bronze interpretive plaques set in granite boulders depicting animals in war, along with facts about their service. The paw and hoof prints of dogs, horses and mules are stamped into the concrete leading to the plaques, while a life-sized statue of a medical service dog symbolically stands guard over the site.

Share on Facebook

Share on Facebook Share on X

Share on X Share by Email

Share by Email Share on Google Classroom

Share on Google Classroom