The CIM-10B Bomarc was the world’s first long-range, nuclear capable, ground-to-air anti-aircraft missile. Two squadrons of the missile were purchased and deployed by the Canadian government in 1958. This was part of Canada’s role during the Cold War to defend North America against an attack from the Soviet Union. Prime Minister John Diefenbaker’s refusal to equip the missiles with nuclear warheads led to a souring of Canada’s relationship with the United States, especially once the Cuban Missile Crisis brought the issue to the fore. The issue split Diefenbaker’s Cabinet and contributed to his party losing the 1963 election.

Background

After the end of the Second World War in 1945, the United States and the Soviet Union entered the Cold War. The North Atlantic Treaty Organization (NATO) was created on 4 April 1949. It was Canada’s first peacetime military alliance. It placed the country in a defensive security partnership with the United States, Britain and Western Europe. In 1957, fear of a Soviet nuclear attack on North America led Canada and the United States to create the North American Air Defense Agreement (NORAD). It placed continental air defence under joint American and Canadian command.

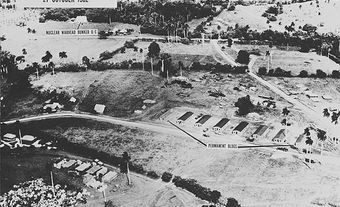

In the fall of 1958, Prime Minister John Diefenbaker announced that as part of Canada’s responsibilities in these alliances, his government would purchase 56 CIM-10B Bomarc missiles. They would be deployed near La Macaza, Quebec, and North Bay, Ontario. Both sites would include custom-built storage and launch facilities and quarters for US personnel. The missiles would replace the increasingly expensive Canadian-made Avro Arrow fighter jets, which at that point were under construction. The missile program would cost less than half of the Arrow program. The savings justified the government’s decision to cancel the Avro Arrow contract. (See Editorial: The Avro Arrow is Cancelled.)

Missile Specifications

The Bomarc was the world’s first long-range, nuclear capable, ground-to-air anti-aircraft missile. The missiles were built in the US by the Boeing Corporation and the Michigan Aeronautical Research Center. They were part of a NORAD defence strategy that used fighter jets and missiles as interceptors; they were to be alerted by lines of radar stations across Canada’s north that would detect a Soviet attack. (See Early-Warning Radar.)

The version of the missile used in Canada was the CIM 10B. It flew farther and had a bigger warhead than the IM-99A Bomarc and the later, faster IM-99B Super Bomarc. The missiles would be fired from the ground at incoming enemy aircraft. They used a booster engine for launch and two Marquardt ramjet engines for speed. A small nuclear warhead was stored separate from the missile, which could travel at a speed of Mach 2.5, at a height of 30,480 m and with a range of 710 km. The range was inadequate for attacking Soviet targets, so the missile were purely a defensive weapon.

Announcement and Reaction

On 20 February 1959, Diefenbaker announced that he was ending the building of the Avro Arrow; he would instead purchase Bomarc missiles from the US. There was immediate criticism from opposition parties and Canadians who believed that killing the Arrow would destroy the country’s aerospace industry. (See Editorial: The Avro Arrow is Cancelled.)

Negative reaction to the Arrow decision led to criticism of the Bomarc missiles. When announcing their purchase, Diefenbaker had failed to mention that they would only be effective if tipped with nuclear warheads; the fact that they would not became public in 1960. The Diefenbaker government then found itself under attack by those who believed that American nuclear weapons were needed in Canada to meet the country’s defence obligations and to keep Canadians safe. Meanwhile, others argued that nuclear weapons should never be allowed in Canada and should, in fact, be abolished altogether. Polls suggested that a minority of Canadians opposed nuclear weapons in Canada. Despite this, anti-nuclear protests became more frequent and determined.

Controversy

The nuclear weapons controversy split Diefenbaker’s Cabinet. Secretary of State for External Affairs, Howard Green, argued against placing nuclear weapons in Canada. Minister of Defence Douglas Harkness, on the other hand, supported arming the Bomarc missiles with nuclear weapons and allowing Canadian forces stationed in Germany to have access to American nuclear weapons if needed. He saw both as an essential part of Canada’s defence strategy.

Diefenbaker tried to appease both sides of the nuclear argument. He stated that American nuclear weapons should not be allowed in Canada without a guarantee that their transportation and storage would be safe. He wanted assurance from the US government and military leaders that Canadian-based nuclear weapons could not be launched without Canada’s approval. Further, he worried about the perceived hypocrisy of accepting American nuclear weapons in Canada while he advocated against nuclear proliferation at international forums.

Cuban Missile Crisis

The nuclear question came to the forefront of public awareness on 22 October 1962. US President Kennedy announced in a televised speech that the Soviet Union was building missile-launching sites in Cuba. They were capable of landing nuclear weapons as far north as Canada. The president demanded that the Cuban sites be dismantled. There was fear around the world that the crisis could escalate into a full-scale nuclear confrontation. But at the end of the 13-day crisis, the Soviets agreed to dismantle their sites in Cuba. (See Canada and the Cuban Missile Crisis.)

Diefenbaker’s refusal to immediately announce support for Kennedy’s action and to quickly bring the Canadian Armed Forces to full alert caused further splits in his Cabinet. In January 1963, NATO’s Supreme Allied Commander General Lauris Norstad said in a press conference in Ottawa that because Canada was not deploying nuclear weapons to its troops in Germany, nor equipping Bomarc missiles with nuclear warheads, it was failing in its obligations to its allies. In February 1963, Defence Minister Douglas Harkness resigned.

The Cuban Missile Crisis and the division in Diefenbaker’s government focussed more attention on whether the Bomarc missiles should be armed with nuclear warheads. The question became an important issue in the April 1963 federal election. The Liberal Party led by Lester Pearson only changed its position to that of supporting nuclear weapons in Canada in January 1963. Pearson campaigned on equipping the Bomarc missiles with nuclear weapons. He also argued that providing Canadian troops in Europe with American nuclear weapons was an essential part of Canada’s NORAD and NATO obligations. Diefenbaker argued that housing American nuclear weapons in Canada would be dangerous and represented a breach of Canadian sovereignty.

The nuclear weapons question and Diefenbaker’s handling of the issue were major factors in the Liberals’ victory in the election. As prime minister, Pearson fulfilled his campaign promise; on 31 December 1963, the Bomarc missiles in Ontario and Quebec were affixed with American nuclear warheads.

End of the Bomarc Missiles

Pierre Trudeau succeeded Lester Pearson as prime minister on 20 April 1968. The next year, his government announced that Canadian forces would no longer be supplied with nuclear weaponry; this was to be part of Canada’s new defence policy, as well as a show of Canada’s support for the Nuclear Non-Proliferation Treaty. All American nuclear weapons stationed in Canada, including those specific to the Bomarc missiles, were returned to the US by 1972. The Bomarc missiles were decommissioned and used as target drones by the US Air Force. The bases and launch pads in Canada were disassembled and sold as scrap metal.

See also Canada and Weapons of Mass Destruction; Armaments; Operation Dismantle; Canadian-American Relations; Canadian Foreign Relations; Middle Power.

Share on Facebook

Share on Facebook Share on X

Share on X Share by Email

Share by Email Share on Google Classroom

Share on Google Classroom