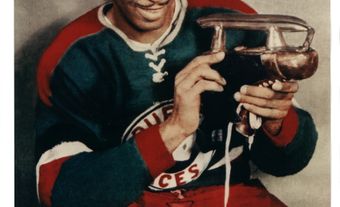

Larry Kwong (born Eng Kai Geong), hockey player (born 17 June 1923 in Vernon, BC; died 15 March 2018 in Calgary, AB). On 13 March 1948, Kwong became the first Chinese Canadian to play a National Hockey League (NHL) game. He also had a long career in professional hockey in Switzerland as a player and a coach. Kwong has been inducted into the Okanagan Sports Hall of Fame, the BC Sports Hall of Fame and the Alberta Hockey Hall of Fame. In December 2022, Parks Canada commemorated him for “breaking racial barriers in the National Hockey League.”

Growing up in British Columbia

Larry Kwong’s father came to Canada in 1884 on a clipper ship. Heoriginally settled in Cherry Creek, British Columbia, where he tried to mine for gold. Unable to find his fortune, Kwong’s father moved to Vernon. In 1895, he opened a grocery store called Kwong Hing Lung, which translates to “Abundant Prosperity.” He had 15 children — Larry, the second youngest, was born Eng Kai Geong on 17 June 1923.

The year Kwong was born (1923), the Canadian government passed the Chinese Immigration Act (Chinese Exclusion Act), which effectively banned Chinese immigrants from entering the country. The strongest calls to ban Chinese immigration came from British Columbia. In a 2011 interview with CHBC News in Kelowna, Kwong recalled that, “When I was a young boy, I couldn’t just go to any barber shop [in Vernon]. They won’t take me because I was Chinese. It didn’t make me feel good.”

Early Hockey Experiences

When Larry Kwong was only five years old, his father died. His mother took over managing the store, and it was there that he spent much of his time. Like many Canadian children, hockey was a major part of Kwong’s childhood. In a 2009 interview, he remembered going to the top floor of the store every Saturday night to listen to Hockey Night in Canada on the radio. Next to the store, his brothers created a hockey rink by dumping water on an empty lot.

Kwong had to beg his mother to buy him skates. She wasn’t very supportive of him playing hockey at first, but finally agreed that he could play as a reward for helping with various duties. She bought him a pair of skates that were too big, so he would grow into them over the next few winters.

Kwong started playing minor hockey in Vernon at the age of seven. Almost from the beginning, racist attitudes affected his experience in hockey. Once, when he was nine, his team was scheduled to play in Nelson, BC. Due to the poor weather, they had to travel through the United States. Even though Larry had a birth certificate that showed he was born in Canada, he was not allowed into the US.

A clever and talented centre, Kwong led the Vernon Hydrophones to the 1939 BC Midget Championship and then the 1941 BC Juvenile Championship. However, with his success came frequent references to his Chinese ethnicity. As a teenager, Kwong was nicknamed the “China Clipper” or “King Kwong.” In the 2011 interview with CHBC News, Kwong remembered that reporters at the time “would say ‘Chinese boy scored so many goals’.”

For the 1941–42 season, Kwong joined the famous Trail Smoke Eaters of the Alberta–British Columbia Hockey League. He scored a very respectable 9 goals and 13 assists for 22 points in 29 games. However, Kwong experienced racism in Trail, too. While his teammates received high-paying jobs at the local smelter, Kwong was only offered a job as a bellhop at a local hotel.

Second World War

In 1944, Kwong was drafted into the army and stationed in Wetaskiwin, Alberta. He explained to Pacific Rim Magazine in 2012 why he was not drafted until the later stages of the Second World War: “At the time, they didn’t want the Chinese to be in the army. Then near the end of the war, they decided to draft us. I was drafted and then I had my basic training.”

Kwong originally thought that he would be given an assignment overseas, like so many other Canadian soldiers. Instead, he was instructed to play hockey and entertain the troops. Kwong played for the Red Deer Army Wheelers of the Central Alberta Garrison Hockey League, a temporary league that was open to the military. One of his teammates was Jim Henry, a goaltender with the New York Rangers. In an ironic twist, “hockey probably saved [Kwong’s] life” according to BC Sports Hall of Fame curator Jason Beck.

New York Rangers

In 1945–46, Kwong played one more season as a centre with the Smoke Eaters, recording 12 goals and 8 assists for 20 points in 19 regular season games. He also played in 10 playoff games for Trail that year and recorded eight goals and one assist for nine points, as the Smoke Eaters won the 1946 Savage Cup (BC Senior A Ice Hockey Championship).

After his season with the Smoke Eaters, Kwong attended a New York Rangers hockey school in Winnipeg in September 1946. He impressed Rangers scout Al Ritchie and was awarded a contract to play with the Rangers’ top minor league affiliate, the New York Rovers of the Eastern Amateur Hockey League. Kwong also moved from centre to right wing.

Like the New York Rangers, the Rovers played at the famous Madison Square Garden. Kwong became very popular in New York’s Chinese community. He was given the keys to New York’s Chinatown and was often seen in its nightclubs, surrounded by beautiful waitresses.

Single Game in the NHL

In 1947–48, Kwong led the Rovers with 86 points. It was also the season he got his chance to play for the New York Rangers. On 13 March 1948, Kwong played for the Rangers against the Montreal Canadiens at the Montreal Forum (the Rangers lost the game 3–2). He had only one minute of ice time in a single shift — not enough time to prove his worth to the team. Kwong never played an NHL game again.

Years later, he still felt disappointed with the lack of ice time. “I didn’t get a real chance to show what I [could] do,” he told the New York Times in 2013. Kwong also expressed his frustration in an interview with the Multicultural History Society of Ontario in 2009: “Just a minute. So, what can you do in a minute? Unless you’re a real magician, what can you do in a minute?”

Seven Years in Quebec

Disappointed by his brief experience in the NHL, Larry Kwong left the Rangers following the 1947–48 season to play hockey in Quebec. From 1948 to 1955, Kwong was a regular member of the Valleyfield Braves, where he was coached by the legendary Toe Blake. (Blake coached the Braves from 1951 to 1954 and later coached the Montreal Canadiens, winning eight Stanley Cups.)

Kwong’s best season with the Braves came in 1950–51. Kwong, who had returned to centre, and teammate André Corriveau were the Quebec Major Hockey League’s (QMHL) co-leaders in assists with 51. That season, Kwong was also third in goal-scoring (34) and second in points (85). With Kwong and Corriveau providing the necessary offence, the Braves won the first Alexander Cup in 1951, a “Major Senior” national championship open to both professional and amateur teams. For his outstanding year, Kwong won the Byng of Vimy Trophy, awarded to the QMHL most valuable player, and was a QMHL first all-star team selection at centre.

Kwong also played against the legendary Jean Béliveau, who was a member of the Quebec Aces at the time. Béliveau had great admiration for Kwong’s abilities: “Larry made his wing men look good because he was a great passer. He was doing what a centre man is supposed to do” (New York Times, 20 February 2013).

After leaving Valleyfield, Kwong played the 1955–56 season with the Trois-Rivières Lions. He also played parts of two seasons (1955–57) with the Troy Bruins of the International Hockey League, and one season with the Cornwall Chevies of the Eastern Ontario Senior Hockey League (1956–57).

European Hockey Career

In 1957, Larry Kwong’s playing career was far from over. He spent an additional seven years playing in Europe — one in Great Britain and six in Switzerland. In his one season in the British Hockey League (1957–58), he scored 55 goals in 55 games with the Nottingham Panthers.

From 1958 to 1964, Kwong both played and coached in Switzerland, where he was the first Asian coach of a professional hockey team. After his playing career ended in 1964, Kwong spent nine more seasons coaching hockey in Switzerland. He also coached tennis there.

Life after Hockey

Kwong returned to Canada in 1972 to operate a grocery store in Calgary, Alberta, with his brother Jack. He was very active in the community and held season tickets for the Calgary Stampeders for over 35 years.

Recognition and Honours

After being overlooked for decades, Kwong began to receive recognition for his accomplishments in the 2000s. In 2009, the Society of North American Hockey Historians and Researchers presented him with a Heritage Award to commemorate the 60th anniversary of when he broke the NHL’s colour barrier. He also received the City of Calgary’s Asian Heritage Month Award in 2009 and the inaugural Pioneer Award from the Okanagan Hockey Group in 2010.

In 2011, Kwong was inducted into the Okanagan Sports Hall of Fame in Vernon. He was inducted into the BC Sports Hall of Fame in 2013 and the Alberta Hockey Hall of Fame in 2016. His story was featured in the award-winning documentary Lost Years: A People’s Struggle for Justice (2011). In 2014, an hour-long documentary titled The Shift: The Story of the China Clipper was broadcast in Cantonese, English and Mandarin on Omni Television.

On 11 December 2022, Parks Canada designated “breaking racial barriers in the National Hockey League” as an event of national historic significance that was achieved by five players between 1931 and 1958: Paul Jacobs, Henry “Elmer” Maracle, Larry Kwong, Fred Sasakamoose and Willie O’Ree. A ceremony was held at the Hockey Hall of Fame to celebrate the designation.

By March 2023, a campaign to have Kwong inducted into the Hockey Hall of Fame had compiled a petition with more than 8,600 signatures. Long-time New York City sports reporter Stan Fischler, who covered the Rangers, said in an interview, “Larry belongs in the Hall of Fame. What bugs me is that I never heard a reason why the Rangers did not give him more of a chance. I watched Larry for two years. He was an ace.”

Share on Facebook

Share on Facebook Share on X

Share on X Share by Email

Share by Email Share on Google Classroom

Share on Google Classroom