Origin

The first point blankets were created by French weavers who developed a “point system” — a way to specify the finished size of a blanket — sometime in the 17th century. (See alsoWeaving.) The term “point,” in this case, originates from the French word empointer, which means “to make threaded stitches on cloth.” The points were simply a series of thin black lines on one of the corners of the blanket, which were used to identify the size of the blanket. Though the points on the blankets did not have an inherent value, merchants during the fur trade often priced point blankets according to the number of points on the blanket, with one point assigned for small blankets and four points designated for very large blankets.

History

The Hudson’s Bay Company (HBC) had been trading blankets since the company incorporated in 1670. By 1700, blankets comprised more than 60 per cent of goods exchanged in the fur trade. The HBC did not commission its very own point blanket until 1779. During a job interview with the Hudson Bay House in London, England, that year, Germain Maugenest, an independent and experienced fur trader, offered suggestions to improve the company as part of his service to the HBC. One of his recommendations included regular stock and trade of “pointed” blankets. A month later, the HBC commissioned the Witney mills — a collective name for textile mills in Witney, Oxfordshire in Britain — to produce “30 pair[s] of 3 points to be striped with four colors (red, blue, green, yellow) according to your judgement.” (See alsoWoven Textiles.)

During the fur trade, the value of trade goods, including blankets, was compared to “made beaver” pelts (finished and processed pelts), not to blankets. However, the point system made it easy to sell the blankets through fur trading, as the points became a reliable pricing convention. At first, a one-point blanket was worth one beaver pelt. However, as the HBC moved out into the Pacific Northwest in the early 19th century, there were less beavers around, and therefore beaver pelts started to lose their value as the staple fur. The point blankets then became the standard for measuring every item the HBC was trading. In fact, the blanket had become so synonymous with the standard measure for trade that in the HBC records, the term “blanket” was used to convey a collection of smaller trade goods.

The Bay Blanket. These warm blankets are as iconic as Mariah Carey's lip-syncing, but some people believe they were used to spread smallpox and decimate entire Indigenous communities. This Secret Life of Canada episode dives into the history of The Hudson's Bay Company and unpacks the very complicated story of the iconic striped blanket.

Note: The Secret Life of Canada is hosted and written by Falen Johnson and Leah Simone Bowen and is a CBC original podcast independent of The Canadian Encyclopedia.

Uses

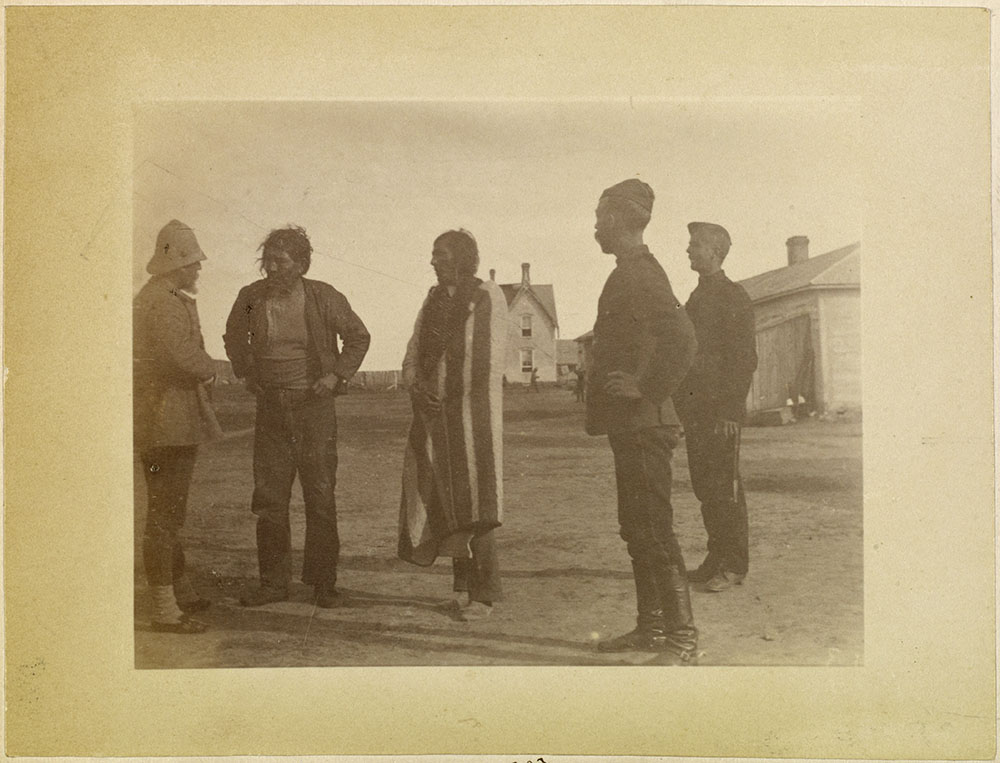

Point blankets were bought by Indigenous and settler communities alike to use as bedding, clothing, room dividers and fabric for other items. Prior to the European blanket trade, many Indigenous nations wore hand-woven blankets made of animal hides and furs. Blankets played an important role in many Indigenous communities as all-purpose clothes and household items, as well as status symbols. (See alsoChilkat Blanket.)

Point blankets were also sometimes used in the potlatch, a gift-giving feast practiced by various First Nations communities in the Pacific Northwest, including the Haida, Tlingit, Nuu-chah-nulth, Kwakwaka’wakw and Coast Salish. To show their wealth during potlatches, participants cut blankets into many small pieces so that everyone at the potlatch would receive a gift. Often these small pieces were collected by weavers, unraveled and then woven into a new blanket. Occasionally, therefore, the wool used in the Hudson’s Bay Point Blanket mixed with traditionally-sourced wool to form a new creation. Before the point blankets arrived in North America, Indigenous blankets were used in such ceremonies. For many Coast Salish nations, the point blankets led to the decline of traditional weaving skills as HBC blankets became more plentiful and accessible.

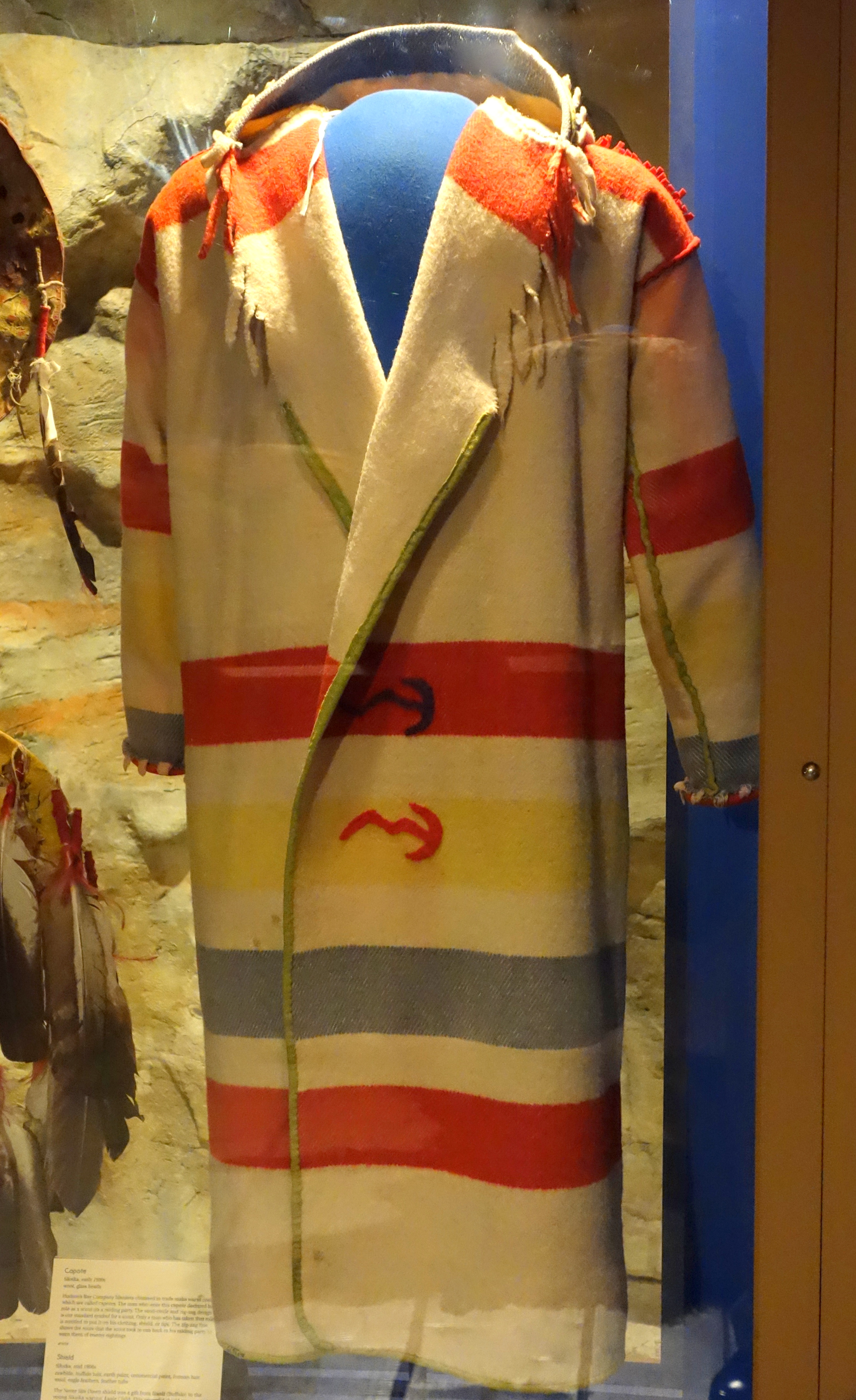

In central and eastern Canada, many Métis and French settlers and traders wore their Hudson’s Bay Point Blankets as outerwear robes, and later turned them into capotes — handmade wrap-style coats. Capotes became so popular that, in 1706, the HBC hired a tailor to construct the blankets into these coats. The capote was particularly popular with trappers as the wrap style made it easy to move and hunt in, while keeping them warm.

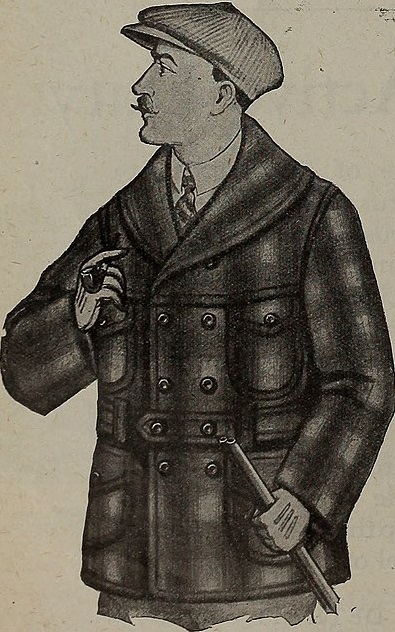

In 1811, a new style of coat was created using the point blanket: the Mackinaw, a shorter coat with a double-breasted style. The Mackinaw was created after British Captain Sir Charles Roberts found the winter in a fort near Sault Ste. Marie, Ontario, too cold, and commissioned settler and Métis women to create 40 coats for his men out of 3.5 point blankets.

In 1922, the HBC introduced its first commercial blanket coats, which had the doubled-breasted lapels of the Mackinaw and the longer length and hood of the capote. By 1929, the HBC launched a full line of blanket coats for women, men and children. (See also Cowichan Sweater.)

Today, the distinctive design of point blanket strips has been used as part of the HBC Collection brand on products ranging from umbrellas to smart phone cases. The point blanket has become an icon of Canadian style, often featured in Canadian home and style magazines and blogs. (See alsoFashion Design in Canada.)

DID YOU KNOW?

The most iconic Hudson’s Bay Point Blanket colours — white with red, indigo, green and yellow stripes — have no specific meaning. The colours were popular when the blankets were first produced, and are sometimes known as Queen Anne’s colours, as they were favoured during her reign (1702–14).

Design

Hudson’s Bay Point Blankets were traditionally made in plain red, white, green or blue background, with a single bar (called “heading”) of indigo on either end. Over the years of fur trading, the design of point blankets grew to accommodate the preferences of various Indigenous nations. For example, when the HBC first established trading posts and forts in the Pacific Northwest, Coast Salish women — who had been weaving blankets out of mountain goat and dog hair since well before European contact — became determined to get high-quality point blankets. Chief factor for the HBC’s Columbia District, John McLoughlin, informed the company in 1845 to make blankets resembling the more favourably-designed American point blankets: “The American Blanket though generally inferior to ours, meets a readier sale with Indians in consequence of its gaudy color and we beg that those we have ordered may be made in respect of color and texture fully equal to the samples.” Therefore, when the Coast Salish preferred a purer white colour, the HBC complied. Occasionally, Coast Salish women would sew in folds and add borders to adjust the size and form of the point blankets for ease of use.

In other Indigenous communities, the preferred design of point blankets differed. For example, many Inuit liked plain white blankets that provided camouflage, while the Tsimshian and Tlingit typically preferred deep blue designs. Nuu-chah-nulth nations tended to like green blankets, and in many Coast Salish communities, red. Though the reason for these differences is not certain, it is thought that certain patterns and colours held important spiritual meaning, as well as practical use. (See also Religion and Spirituality of Indigenous Peoples.) Trade blankets were so popular on the West Coast that British weavers altered the colours of designs to meet local demand.

By 1929, the HBC expanded their variety of colours in order to make the blankets an essential part of home décor. Occasionally, the HBC would produce blankets for special events or anniversaries; for instance, for the coronation of Queen Elizabeth II, a royal purple blanket with white stripes and point was produced. According to the HBC, the hue and colour order in the famous white and colour-striped point blanket were not standardized until the mid- to late-19th century.

DID YOU KNOW?

In 1916, Pendleton, an Oregon-based blanket company, created its Glacier Stripe design, which uses the same stripe and colour design as the Hudson’s Bay Point Blankets. The HBC sews a label of authenticity in one corner of their point blankets in order to distinguish them from similar-looking blankets. The Glacier Stripe blankets continue to be produced today through Pendleton.

Controversy

For some Indigenous peoples, the point blanket represents the forces of colonization. Cree artist Kent Monkman uses the point blankets in his series of paintings, “Shame and Prejudice: A Story of Resilience,” as a representation of “the imperial powers that dominated and dispossessed Indigenous people of their land and livelihood.” In 2011, Anishinaabe artist Rebecca Belmore created the video installation “The Blanket,” which features Winnipeg dancer Ming Hong rolling down a snow-covered hill in a point blanket. Belmore argues that while the “blanket is an object of beauty, a collector’s item that belongs to the Hudson’s Bay Company’s history,” it is, for many Indigenous peoples, “still viewed as a trade item that once contained the gift of disease.”

Belmore is referring here to the history of Europeans intentionally giving blankets contaminated with smallpox and other infectious diseases to Indigenous peoples. The story originates in a notorious series of letters from the 1763 Pontiac Uprising in Fort Pitt, Pennsylvania, in which Jeffrey Amherst, Commander-in-Chief of British Forces in North America, encouraged the use of blankets infected with smallpox as a means of biological warfare: “You will Do well to try to Innoculate [sic] the Indians by means of Blankets, as well as try every other method that can serve to Extirpate this Execrable Race.” While there was an outbreak of smallpox among the Indigenous peoples around Pennsylvania that spring, the disease had already been in that area, and it is therefore unknown if Amherst’s thoughts were put in action.

Some scholars, such as historian Robert Boyd and artist and anthropologist Marianne Nicolson, believe that colonial authorities knew that smallpox would spread into Western Canada, and that it would help colonial authorities claim Indigenous lands without treaties or compensation. Even if they did not intend to use the blankets to spread smallpox, trading blankets easily allowed for the transferring of European diseases to Indigenous people.

While the HBC acknowledges that smallpox decimated Indigenous populations across Canada, it states that its company “had nothing to do with the use of smallpox blankets as biological warfare.” In fact, the company claims that HBC employees tried to stop the spread of disease by practicing quarantine and providing care for the infected.

Share on Facebook

Share on Facebook Share on X

Share on X Share by Email

Share by Email Share on Google Classroom

Share on Google Classroom