An Algonquin man declared to Jesuit missionary Paul Le Jeune in 1639: “To live among us without a wife is to live without help, without home and to be always wandering.” While the importance of having a home and wife may have been lost on the itinerant and celibate Jesuit priest, for many First Nations this quote evokes the social, economic and political advantages of marriages, especially in the context of the fur trade. Indigenous women’s labour produced and mended clothing, preserved meats, harvested maple sugar and root vegetables like turnips, trapped small game, netted fish and cultivated wild rice — all crucial survival and subsistence activities in the boreal forests, prairie parklands and northern plains of fur trade society. Through intraclan marriages (see Clan), First Nations women forged extended kin lineages, established social obligations and reciprocal ties, and negotiated for the access and use of common resources across a vast and interconnected Indigenous world. Marriages between different Indigenous villages, clans and nations shaped regional politics, fostered lateral marital alliances and created a geographically diverse and widespread kinship network throughout the Great Lakes- St. Lawrence River Basin, the Hudson Bay watershed, and the Pacific Slope (see Pacific Ocean and Canada.)

Indigenous Trade Protocols and Kinship

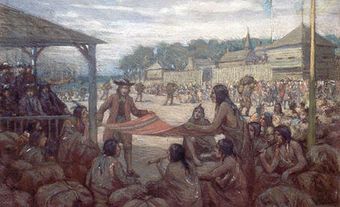

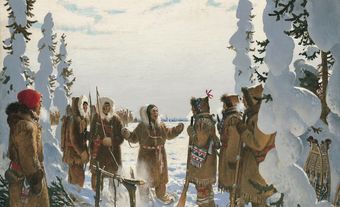

When European mariners first began bartering with First Nations along the Atlantic seaboard for various animal pelts (see Beaver Pelts), they encountered a complex preexisting system of Indigenous alliances and exchange networks. To trade in this overwhelmingly Indigenous world, English and French newcomers had to learn how to play by the rules, which included respecting trade protocols, ceremonial gift-giving, fostering reciprocal relationships and acknowledging family obligations. The fur trade acted as an important social glue that bound Indigenous peoples and newcomers together. Because most First Nations essentially recognized two categories of people — foreigners or relatives — establishing kinship ties to transform strangers into relatives was a prerequisite before commercial exchange could occur. To achieve this, Indigenous peoples often imposed their own conceptions of kinship through adoption or marriage to create reciprocal social connections with the French and English. Indigenous women were central to creating these social connections between Indigenous peoples and newcomers.

Fur-Trade Marriages

Young European fur-trade merchants, voyageurs and labourers who usually originated from settler colonies or trading outposts with few or no European women happily acquiesced to First Nations offers to enter marital unions with Indigenous women. The French referred to this common-law fur-trade union as “mariage à la façon du pays”; the English referred to these intimate relations as “marriages according to the custom of the country.”

Fur-trade marriages created kinship ties, bridged political, social and commercial relations between Indigenous peoples and newcomers and became the basis for a fur-trade society in North America. In the fur trade, Indigenous women were not merely casual bedmates but were also essential contributors to the functioning and conduct of the trade itself. Indigenous wives served as crucial commercial liaisons between their European husband and their male kin — fathers, uncles, brothers and cousins — which established a familial relationship based in obligations, responsibility and interdependence. For an Indigenous father, a new son-in-law could be a significant economic contributor through his generosity and connections to European merchandise, trade goods and emergency provisions in times of famine. For a European husband, he could count on support from his in-laws and his wife’s other relatives for access to favourable terms of trade, provisions and for protection and shelter against the elements and enemy First Nations. Far from being simply a commercial exchange, the fur trade revolved around familial and marital relations, and the central role of Indigenous women ensured that the fur trade remained an exchange process rooted in an Indigenous worldview and governed by kinship.

Indigenous wives were also cultural go-betweens, indispensable intermediaries for their fur-trader husbands; they facilitated communication between societies who spoke different languages (see Indigenous Languages in Canada) and taught their husbands how to survive and thrive in Indigenous territory. Even though Euro-Indigenous marriages occurred in the fur trade country outside the purview of the Church, they were true marital unions in every sense of the word. As historian Sylvia Van Kirk states: “in spite of its many complexities and complications, ‘the custom of the country’ should be regarded as a bona fide marital union.” Because family obligations and kinship networks were at the centre of the fur trade, it should not be surprising that its prolonged history resulted in salient cross-cultural and cross-community exchanges that eventually gave rise to new peoples, particularly the Métis Nation of Western Canada. Ultimately, through intermarriage, Indigenous women became central to the fur trade as pivotal links between their birth communities and those of European and Canadian traders.

Gender Roles

First Nations wives and European husbands negotiated their respective gender roles in the fur-trade context. French and English fur traders and voyageurs provided generous gifts and issued ample trade goods on credit in the winter for repayment in the summer. In return, Indigenous women fulfilled traditional gender roles such as food production (primarily through berries, maple sugar and small game), netting snowshoes, making and mending clothing and constructing or repairing birchbark canoes.

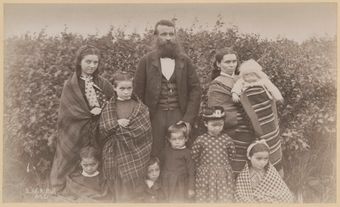

European men who married into Indigenous families benefitted from relationships that helped improve their quality of life considerably. A fur trade marriage assured a European husband’s inclusion in Indigenous social life, secured personal safety and facilitated access to furs through his in-laws and other extended kin. While a husband was away engaged on business, Indigenous women managed hearth and home, preparing food, chopping wood, mending clothing and even making valuable survival items such as moccasins or snowshoes.

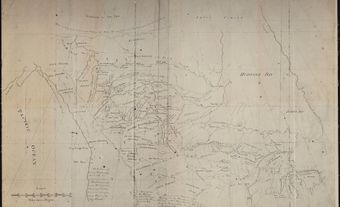

Within the context of fur-trade marriages, First Nations women continued to enjoy close relations with their communities. Since kin ties granted access to territory and resources, Europeans who married into First Nations drew on their wives’ families to access areas available for hunting, wild rice harvesting and fishing. In the end, for French and English newcomers, marriage to First Nations women transformed the local environment from a harsh and foreboding wilderness to a legible and comprehensible landscape with clearly articulated relationships, resources, territorial boundaries and reciprocal obligations both to the human and nonhuman world.

The degree of influence that Europeans and Euro-Canadians attained in First Nations communities was based on the seriousness with which they took their marriage and kinship obligations. Those who became community fixtures by returning seasonally to bring trade goods and to raise families generally found that their influence grew. Indigenous peoples themselves played an important role in ensuring that the usual patterns for sexual relations between their women and European traders took the form of sanctioned marital unions. Fur traders who wished to marry a woman had first to obtain the consent of her parents. Once permission was obtained, the fur trader had to pay a bride price or dowry, such as a gift of blankets, woollen cloth, kettles or alcohol.

Traders who sought to side-step the formalities of fur trade marriages or who offended Indigenous customs ran the risk of serious reprisal. As one old North West Company (NWC) voyageur would later explain, custom had to be observed: “Almost all nations are the same, as far as customs are concerned… There is a danger to have your head broken if one takes a girl in this country without her parents’ consent.” Although initially strategic in nature, fur trade marriages between Indigenous women and European men sometimes led to stable, long-lasting unions built upon a foundation of loyalty and mutual affection. Some of these examples evoke Hudson’s Bay Company (HBC) Chief Factor James Douglas’s phrase of 1842 to describe some fur trade marriages between HBC servants and First Nations women: "the many tender ties, which find a way to the heart."

Limited Scope

Not all Euro-Indigenous encounters resulted in the same cross-cultural sexual and marital relationships. Fur-trade marriages were not a forgone conclusion because the gender norms that regulated various Indigenous societies differed greatly across place and time. Some Indigenous peoples, like the Inuit, Mi’kmaq and Niitsítapi (Blackfoot), did not pursue widespread fur-trade marriages with European newcomers for a variety of political, social, spiritual and commercial reasons. Throughout most of Canadian history, Indigenous peoples largely set the guidelines for gender relations, marital practices and sexual interactions between Indigenous women and European men, which differed greatly across cultures. In other words, if marriages between Indigenous women and European traders occurred at all, it was because First Nations women and men desired such unions with the French and English newcomers to forge commercial, political and military alliances. Indigenous peoples dictated the gendered terms of kinship that defined Euro-Indigenous relations in the context of the Canadian fur trade.

Abuses

There was, however, a less savoury side to fur-trade marriages. Not to be romanticized, abuses, abductions, rape and abandonments were commonplace. European and First Nations men alike forced Indigenous women into opportunistic marriages to secure trade partnerships and kinship ties. These marital alliances were not always long-lasting or loving, and many fur traders shirked marital and paternal responsibilities, eventually abandoning their Indigenous wives and in some cases their fur-trade families altogether.

As the fur trade rivalry between the NWC and the HBC intensified in the Athabasca Country in the late 18th century, Dene women in particular suffered abuses at the hands of extortionist traders who sometimes forcibly seized Indigenous women as commodities for unpaid wages or debts. As ethnohistorian Jennifer Brown points out, scholars examining the more negative aspects of the fur trade “have found ample grounds to argue that abuse of women, neglect, prostitution, family breakup and other social problems were also part of fur trade life.” Ultimately, there was considerable variability to the relationships between Indigenous women and European men in the context of the Canadian fur trade.

Share on Facebook

Share on Facebook Share on X

Share on X Share by Email

Share by Email Share on Google Classroom

Share on Google Classroom